Between the Mountains and the Sea by Peter Pearson

We reproduce below an extract from the Killiney chapter of Peter Pearson’s book of 1998 (revised 2007) which provides an excellent overview of the history and a detailed description of the natural and built physical fabric of the district. In this article we have not included Peter’s descriptions of the significant houses in the area but have kept to the more general historical commentary. As time allows we will be adding to the articles on individual houses and as further information becomes available the list of houses will be updated by this website. See here for current list of houses. Supporting images are provided by KillineyHistory.ie.

PETER PEARSON Peter Pearson is a painter by profession, but has had a lifelong interest in the protection and enhancement of historic buildings. A graduate in art history from Trinity College Dublin, he is author of a variety of architectural publications, including Dun Laoghaire/Kingstown (1981), The Heart of Dublin (2000) and Decorative Dublin (2002), An Taisce publications such as Restoring Your Old Building (1984) and Temple Bar, Saving the Area (1985). He is co-author of The Royal St George Yacht Club (1987) and The Forty Foot (1995), and contributor to Dublin’s Victorian Houses, The Book of Dun Laoghaire, The Book of Bray (1987), Gaskin’s Irish Varieties, Dun Laoghaire Guide (1978), Department of the Environment Conservation Guidelines (1996), History of Dublin Hotels and RDS and History of Bewley’s.

He was the founder of the Drimnagh Castle Restoration Project and a founder member of the Dublin Civic Trust, was a former member of the board of directors of the Irish Architectural Archive and a member of The Heritage Council and an honorary life member of the Dun Laoghaire Historical Society. Peter now lives in Shankill where he is restoring a period house.

Chapter 4

Killiney

Killiney is noted for its hills which command excellent views of Dublin Bay, the Irish Sea and the surrounding mountains. The obelisk on the summit of Killiney Hill is a conspicuous landmark of the area, and has been part of the scenery since the middle of the eighteenth century. It was this special scenic quality which in the nineteenth century first attracted developers to build houses in this area, giving it the distinctive residential character which it still retains. As we shall see, these hills and their slopes were almost devoid of any buildings during the eighteenth century, apart from the famous obelisk and the ancient ruined church. By 1839, when Samuel Lewis was compiling his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, there were already many ‘favourite places of residence, and several pretty villas and rustic cottages’ in the area.

Killiney extends over a large area stretching from the bay across by Ballybrack and west as far as Glenageary, while to the north it encompasses Killiney Hill itself and is bounded by Dalkey. By the middle of the nineteenth century Killiney was firmly established as one of Dublin’s most favoured residential quarters and today this reputation remains unchanged as house prices become ever higher and ever more unreal.

It is a particularly attractive area, with its many trees, beautiful gardens and south-facing slopes which have the benefit of a sea view. There is also easy access to the beach. It is what estate agents like to call a ‘mature’ area, well furnished with large gardens, shrubs and trees, properties bounded by stone walls and with a wide variety of architectural styles. From Killiney village, the narrow Killiney Hill Road winds downhill towards Shanganagh, while to the east the DART station provides convenient access to trains bound for the city.

It is the western portion of Killiney which has changed most, where beyond Killiney golf course many new houses were built at Avondale, Ballinclea, Watson’s and Ballybrack.

The Druid’s Chair, which, though it looks like a prehistoric burial mound is considered by some to be a fake, is probably the oldest monument in Killiney. It was opened up during the eighteenth century when three stone cists were found there, and, in the fashion of the time, a grove of oak trees was planted. It is thought that some of the excavated stones were re-arranged to form the so-called Druid’s Chair.

Charles Vallancey Pratt, a noted antiquarian, inspected the monument in the early nineteenth century and believed it to be genuine, and so it came to be marked on the early Ordnance Survey maps as a ‘Pagan Temple’. Later historians such as William F. Wakeman, the antiquarian, condemned it as a forgery, nonetheless many houses in the immediate vicinity were taken with its romantic antiquity and were given such names as Mount Druid, Druid Hill, or Temple Hill.

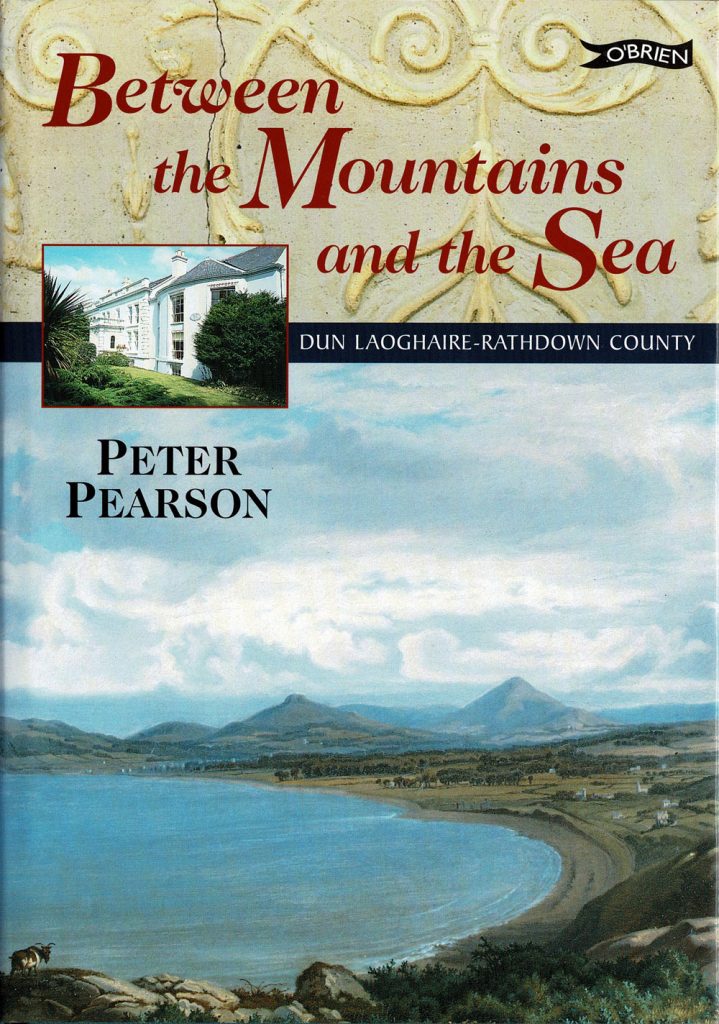

The name Killiney is derived from the Irish, Cill Inion Leinin, which translates as ‘the church of the daughter of Lenin’. The ancient ruined church of Killiney is delightfully situated among trees on Marino Avenue and must originally have had an excellent view of the sea. As the roughly circular aspect of the site suggests, the church may have been erected inside a rath or older place of worship.

The church is dedicated to the daughters of Lenin, who are thought to have established a religious settlement here in the seventh century. The small-scale proportions of the sturdy church are pleasing to the eye. Its short nave and chancel are connected by a small, stone arch and appear to be of early Norman date. The church remained in use until the seventeenth century when it became a ruin. Among its many interesting features is the flat-headed entrance door with a carving of a Greek cross on its under-side.

Killiney Obelisk has been the subject of much attention since it was built in the 1740s. It was intended as the centrepiece of a great undertaking to plant and landscape the hill, which at first was called Obelisk Hill, and more recently has become known as Killiney Hill. The obelisk was the main attraction of the lands of Mount Malpas or Scalpwilliam in the eighteenth century and visitors were brought by coach, on horseback or walked to the summit to admire the view.

In early times this area was included in the lands of Rochestown and Dalkey Commons and belonged for many centuries to the Norman family of Talbot (the same Talbot of Malahide Castle) and through them the property passed eventually to Colonel John Malpas who, in the early eighteenth century, built a brick house for himself at Rochestown.

It was Malpas who erected the distinctive, cone-shaped obelisk on Killiney Hill, as a marble plaque on it records: ‘last year being hard with the poor the walls around these hills and this etc. Erected by John Malpas June 1742’. This inscription is now very worn and hard to read — indeed, the obelisk itself is in need of general repair. Early engravings show a flight of steps leading up to a viewing balcony, but these were later removed for safety reasons. The winter of 1741-2 was known as ‘the hard frost’ and was a time of much poverty and suffering among the poor. Malpas was one of several landowners who carried out building projects in order to provide some employment.

A smaller structure, sometimes called Boucher’s obelisk, lies partly hidden among the trees and rocks and may be contemporary with its larger parent. The inscription ‘Mount Malpas’ is to be found above the door, and though this was an eighteenth-century name for the park, it is difficult to date this monument with any certainty.

Robert Warren, who owned the estate for much of the nineteenth century, repaired the obelisk in 1840, and it is also possible that he was responsible for building the miniature obelisk and so-called ‘wishing stone’ or pyramid, which stands nearby. Warren was addicted to building, developing and improving his estate, and as we shall see he did so with the best of design and materials. For instance, he erected the elegant, granite-built, gate-lodge tower at Killiney Hill Road, and placed an inscription on it to record the date of its completion — 1853. The tall, ball-capped gate piers which grace this entrance were also probably erected during the eighteenth century, although the present gates are smaller and of a later date. This entrance was somewhat altered about ten years ago, when the derelict tea rooms which adjoined the gate lodge were removed. Warren also built the magical cut-granite archway and gate-lodge which is such a feature of Killiney village. The gateway, which is part of a small house once called Camelot, is surmounted by a castellated rampart which connects with a large circular tower and smaller lookout.

A similar cut-stone, octagonal gate lodge with crenellated gate piers and battlemented walls, was built for Killiney Castle at the Dalkey entrance and is still in use by the hotel.

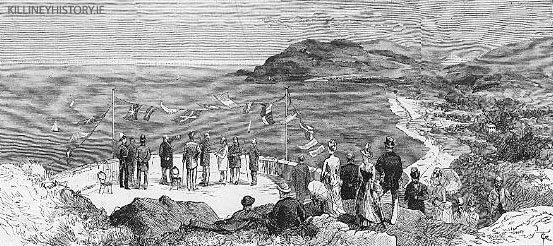

In the park near the obelisk there are also a number of stone-built picnic tables which a nineteenth-century engraving shows in use, with a party of fashionably dressed Victorians enjoying an al fresco meal. Not far off in the woods are the remains of a pump house.

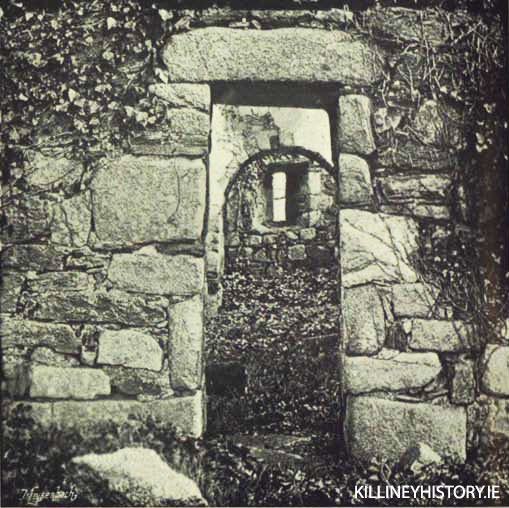

Killiney Castle In 1740 Colonel John Malpas built a house called Mount Malpas, now Killiney Castle, as a speculative development. Malpas must have let the castle in its early years, for in 1752 Falkiner’s Dublin Journal carried the following advertisement: ‘Roxborough, formerly called Mount Malpas, containing 150 acres of land enclosed by a stone wall and a new well-furnished house of six rooms and two large closets on a floor with offices.’

Certainly, Thomas Sherrard’s map of the Malpas estate, made in 1787, shows the castle to be a fairly modest house, with no elaborate gardens or plantations which would compare with Rochestown House, the principal Malpas residence.

Peter Wilson, writing about Dalkey in 1768, says that the new owner of Mount Malpas, the Right Hon. Henry, Lord Viscount Loftus of Ely, had made many improvements to the house and gardens. He comments on the magnificent view of the city, bay and harbour of Dublin, and describes the gardens as being ‘enclosed with high stone walls, stocked with the best fruit trees, and such a collection of flowers as must captivate the most insensible eye’.

Loftus was obviously possessed of a passion for improvement and, like Malpas before him, he carried out other major works in the area, including the cutting of a new carriage road around Killiney Hill, blasting stones and bringing earth to cover the bare out-crops of rock, and planting the west side of the hill with various types of trees and shrubs. Wilson also says that Loftus intended to build a banqueting house in the woods, but never realised his plan because in the meantime he had inherited Rathfarnham Castle, where he directed all his energies.

In 1790 another important landowner, John Scott, Lord Clonmel, leased Killiney Hill with the intention of building a large house there. Clonmel already had a very elegant house at Neptune in Blackrock, but presumably because he was so wealthy and was hungry for new projects, he spent large sums of money on the creation of a deer park at Killiney and employed many men in making roads and building walls.

The castle, which is now the centrepiece of Fitzpatrick’s Castle Hotel, does retain various features of the eighteenth-century structure, despite having been much altered since.

The original Mount Malpas was a seven-windowed, two-storey-over-basement, Georgian house. Sherrard’s map shows the castle in this form. It must have been Robert Warren, the nineteenth-century owner of the Killiney estate, who, in 1840, was responsible for the addition of the mock medieval corner towers, turrets and battlements.

A later inhabitant named Thomas Chippendall Higgin, who bought the castle in 1872, added a half-octagonal castellated tower, cut-stone doorway and entrance porch to the front. The door-case with its carved plaque and swan-neck pediment is in the seventeenth-century style. Higgin had the unusual distinction of being buried on Dalkey Hill in 1906, where a broken cross bears the inscription: ‘Dust thou art, to dust returneth, Was not spoken of the soul’.

Killiney Hill Park, or Victoria Park as it was called when first opened to the public in 1887, had been purchased by the Queen Victoria Memorial Association from Robert Warren Junior for £5000. It was opened by Prince Albert and has remained a public park ever since. Dun Laoghaire Corporation enlarged the park in the late 1930s by purchasing the rest of Dalkey Hill and the lands at Burmah Road, bringing the total area of the park up to two hundred acres. This included the huge area of Dalkey quarry where work first began in 1815 to extract stone for the construction of Dun Laoghaire harbour. The corporation also tried to buy Mount Eagle in order to extend the public park at the Vico Road, but they were outbid at auction by Con Smith, a private buyer. The Vico fields, the now-wild land above the railway at White Rock, had been bought by public subscription in 1926 to prevent any further building from taking place which might spoil its natural beauty— thus it is quite surprising to see large apartment developments now appearing in an area of such high public amenity so close to the lands which the corporation had once tried to purchase to prevent such building.

The Vico Road did not exist until 1889 when it was officially opened to the public by the Lord Lieutenant. Up to then, the eastern side of Killiney Hill was all part of the Warren estate and completely private.

Robert Warren had facilitated the construction of the railway between Dalkey and Killiney by allowing it to traverse his property at the Vico fields. He was, no doubt, well compensated, but was also provided with a private halt (the remains of which can be seen) and a footbridge giving access to White Rock. A massive retaining wall was built at White Rock to carry the railway line above. An interesting detail connected with the sale of Warren’s estate in 1872 was that the purchaser of the lot, which included part of Dalkey Commons, was entitled to gather seaweed from the shore below.

An ambitious plan to develop the entire Killiney Hill estate was drawn up for Warren by the architects Hoskin & Son around 1840 (the plans are in the National Library). The development proposal, which was to be called Queenstown, planned for terraces of very grand houses overlooking Killiney Bay and for other detached residences, and would have completely destroyed the deer park which had been so carefully created in the eighteenth century. Doubtless many of the proposed houses would have been elegantly designed and very well built, rather in the style of Sorrento Terrace, but we must be grateful that this scheme was never executed as we would not today have the great amenity which is Killiney Hill.

The plans also illustrate Killiney Castle, Ayesha Castle and Mount Eagle in small vignettes. These houses were then called Albert Castle, Victoria Castle and Coburg Lodge, all so named in honour of the new British monarch and her consort. The family title of Queen Victoria’s husband was ‘Saxe Coburg’.

Victorian Killiney

The potential for building on the southern side of Roche’s Hill was soon realised, and in the nineteenth century such houses as Glenalua Lodge and The Peak were built. The Peak is a two-storey, five-windowed Victorian house while Glenalua Lodge is a villa-type residence, with a Gothic-style porch. Since then many new houses and bungalows have been erected, taking full advantage of the wonderful sea and mountain views.

After the extension of the railway to Killiney during the 1850s, there was a rush to build houses which would have the advantage of these views and the convenience of easy access to Dublin city. Most of the development took place in the area extending south from Killiney village towards Ballybrack and the sea. More than forty substantial Victorian houses were erected here, an area which was quickly to become a coveted location in which to reside.

But some houses had been built before the arrival of the railway and Samuel Lewis, writing in 1839, lists eight new residences in Killiney including Killiney Park, Saintbury, Killiney House, Marino, Martello Farm, Druid Cottage, Ballybrack Grove and Kilmarnock. Some of the earliest nineteenth-century houses in Killiney were villas, and Mount Malpas is a good example of this type.

The lands of Killiney belonged to the Church since medieval times. In 1842, the ground rents of Killiney, which originally belonged to the Dean of Christchurch, were ‘sold’ to various landlords such as the Domville family, and later the Pim family; and the Church still demanded a tithe from the annual rent. The sale of the estate of George Cecil Pim in 1947 reveals that his family were the chief landlords for all of Killiney, from Seafield Road to Killiney village and from the beach to Shanganagh Terrace.

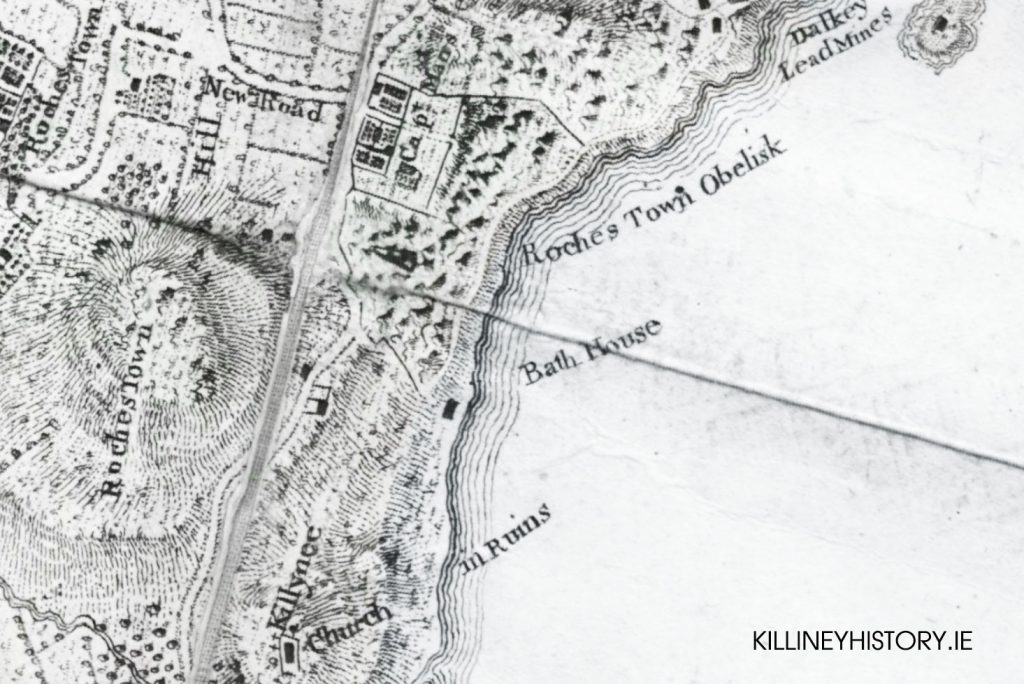

A map made for the Dean of Christchurch Cathedral in 1767, showing his lands which then stretched from Hackettsland to Roche’s Hill, shows only one building, the ancient ruined church. A later survey of 1810 shows that the lands, then let to Compton Domvile of Loughlinstown, had been crossed by new roads which gave access to the Martello towers and batteries which had recently been erected. There were also two small houses on the Military Road, two near the ruined church, one which is possibly Dorset Lodge, and two others near Druid Lodge. There were two further cottages near Killiney village. There is little evidence that there were any houses of note built here before about 1830.

The first Ordnance Survey map of this area, published in 1843, marks Templeville, Glenfield, Killiney Lodge, Killiney House, Desmond, Percy Lodge and Dorset Lodge as the principal houses on Killiney Hill Road.

Many large detached houses of a purely Victorian type were constructed in Killiney in the second half of the nineteenth century, and good examples of these include Marathon, Lismellow, Fortlands, Cliff House and Montebello, all of which are to be found on Killiney Hill Road. Similar houses were built on Killiney Avenue, a new road of the 1850s which linked the residential area of Killiney with the church in Ballybrack. Such houses include Laragh, Clonard and Suquehanna.

All of these large Victorian houses were built to reflect the status and position of the family that lived there. These houses required an imposing front, a grand hall and a well-furnished drawing room. A larger residence with a couple of acres needed a gate lodge and a winding avenue which brought the visitor to a broad gravel sweep in front of the hall door. Whether the architecture was Italianate or Gothic did not matter greatly. Many of the earlier houses were plain, so it was common for wealthy Victorian owners to add porticos, stucco enrichments, cornices and brackets. Often a billiard room would be added at the back of the house.

Killiney is today a place of old stone walls and narrow leafy roads which twist downwards towards the sea or wind upwards into the hills. Strathmore Road, Kilmore Avenue and St George’s Avenue are some of these pleasant lanes, which are dotted with a wonderful variety of houses.

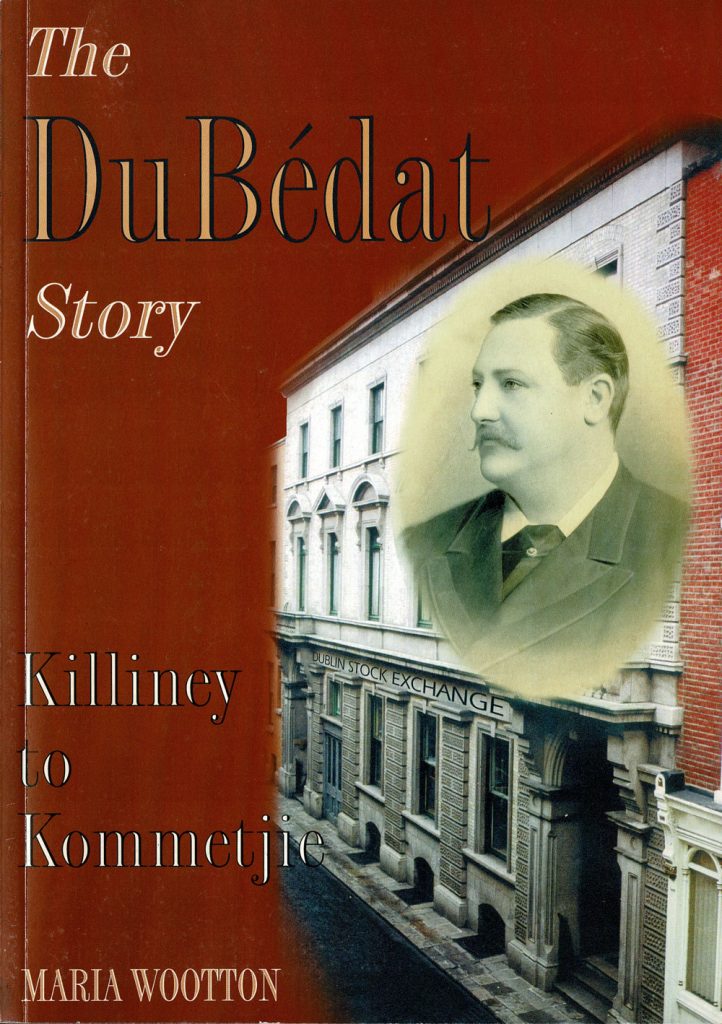

Kenah Hill, earlier called Stoneleigh, was the home of Francis or Frank Du Bedat. Du Bedat became President of the stock exchange in Dublin, but in 1890 he committed a major fraud with his investors’ funds, a crime for which he was ultimately jailed, and the family name ruined. He died in Paris in the 1920s. George Bernard Shaw is said to have modelled his play The Doctor’s Dilemma on the real-life character of Frank Du Bedat.

The writer Katherine Tynan, who lived there for a time, remarked that her grand piano looked like a postage stamp in the drawing room!

There are a number of interesting houses which date from the turn of the century and employ certain mock-Tudor features such as half- timbered gables, mullioned windows, and verandahs, usually in combination with redbrick. Such examples must include Namur, Aileen and Gaileen, all on Killiney Avenue.

The Military Road joins Ballybrack with the railway at Strand Road. It must once have served the Martello tower there and a battery which is now the site of Killiney railway station. Several very large houses were erected on the Military Road including Killacoona, Mentone, Ashhurst, Kilmarnock and Rathleigh.

The family of Field, who were originally wool merchants and butchers, came to own a substantial amount of land in Killiney. William Field, who was a grocer in Ballybrack, obviously enjoyed the pun on his name when he named Seafield Road, which he developed. Some of the houses which Field erected were given names such as Gay Field. William’s Park, called after Field himself, was built close to the present Bayview estate. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Field acquired various leases of lands in Shanganagh and Killiney, which he either sub-let for building or developed himself. His interests included the ground rents from Druid Lodge, Druid Hill, Mount Druid (now Marathon), and other houses in that part of Killiney Hill Road. He also received rents from St Columba’s Church in Ballybrack, and Beechlands, Eaton Brae and Glen Brae, which are all in Shankill.

Killiney Beach has long served as a favourite bathing place and it is not surprising that Rocque’s map of 1757 shows a bath-house somewhere near White Rock. The old tea rooms on the beach are a more modern relic of bathing and boating activities, and though the white-painted structure might look more at home in Greece, it was used up to the 1950s as a dance pavilion and tea rooms. It was also possible to hire rowing boats here at the White Cottage, as it is called locally.

There have been a number of serious pollution problems in Killiney Bay including an oil spill in 1979 and ongoing complaints about sewage. Dublin County Council spent about £5 million in 1981 to improve sewage treatment and to lay a mile-long pipe out into the sea. More recently, the situation has improved and Killiney beach has been awarded the European blue flag, to indicate a high state of cleanliness of the beach and its waters.

As already noted, Killiney’s first railway station was built for the convenience of Robert Warren, almost above White Rock, and possibly in anticipation of his proposed Queenstown development. The station was not convenient to most of Killiney’s new residents, and in 1859 a new one was opened on the site of an old battery or fort and a further station was built at Seafield Road. In 1882, these were abandoned and finally a new Killiney station, still in use, was opened.

The Killiney and Ballybrack Township was formed in 1866 and was responsible for the administration of local affairs. They had the power to levy rates and make improvements in the area. Their duties included the regulation of hackney cars, carriages and cabs, and in 1891 a booklet of bylaws was published for the drivers of these vehicles. There were four stands — one at the railway station, one at Military Road near Ballybrack House, one at Shanganagh Road near Firgrove and one at Killiney Avenue. It was laid down that the heads of the horses should face in a particular direction — for example, at Military Road they were to face the sea! Hackney cabs could carry only four adults and were obliged to use lamps at night. ‘The driver shall wear decent apparel and be civil, and able to read and write, and shall not use any insulting, obscene, or profane language to any person or persons what so ever, nor smoke when employed’, the rules dictated. There was also a full list of charges, for example from Ballybrack post office to any part of Dalkey would cost two shillings, while a trip to the railway station cost one shilling and six pence. Sightseeing trips could be arranged to places like Powerscourt Waterfall or Glendalough, but in these cases fares had to be agreed with the drivers.

Most houses in Killiney and Ballybrack had their own supply of water, usually drawn from wells located near the house. Though the Vartry water supply had been piped from County Wicklow to Dublin in 1868, Killiney remained without its own reservoir until the early 1890s. Shortly after the transfer of Killiney Hill Park to the Township commissioners in 1891, a reservoir was constructed, quite discreetly, into the side of the hill, just above Killiney village. A shelter was built above it, and was used, within living memory, for dancing on summer evenings.

Sir John Gray, who was chairman of the Dublin Water Commission, had bought up the surrounding lands at Roundwood to prevent their purchase by profit-making speculators, and he re-sold them to Dublin Corporation without profit. Gray was the proprietor of The Freeman’s Journal and lived at Lower Strand Road in Killiney, where after his death his house was re-named Vartry Lodge.

We would like to thank Peter for allowing us to reproduce his excellent history of Killiney which has inspired and added considerably to many of the articles hosted on this website.