Introduction

The Saintbury name is derived from Saintbury in Churcham, Gloucester where the father of Frederick Saintbury Parker, Rev. Thomas Parker, was the Rector. Frederick Saintbury Parker was born in 1790 and married Margaret Fitzgerald in 1815. Initially living at Ornee Cottage in Stillorgan they appear to have moved to Saintbury c.1834 and either built or renamed the property Saintbury. In 1832 Frederick was magistrate and chairman of Kingstown Board of Health and lived nearby in Desmond, Killiney. There is also a Parker link to Anglesea in Killiney, in 1829 and 1833, where Frederick is referred to as magistrate and churchwarden. Margaret died in 1865 and Frederick died in 1870. Their eldest daughter Caroline Frances Sydney, b. circa 1818 married William Smith Arthur in 1838. William died in 1839 in France and Caroline then married William Wallace Harris. Caroline died in 1888 and William Harris died in 1891. The house remained in the Harris family until around 1926.

Sub-division of the property

The original house was sub-divided into two individual semi-detached houses (Date unknown but we understand that it was in the 1970’s). The southern end of the original retained the name Saintbury and the adjoining house was named Lynbank.

Saintbury in 1837

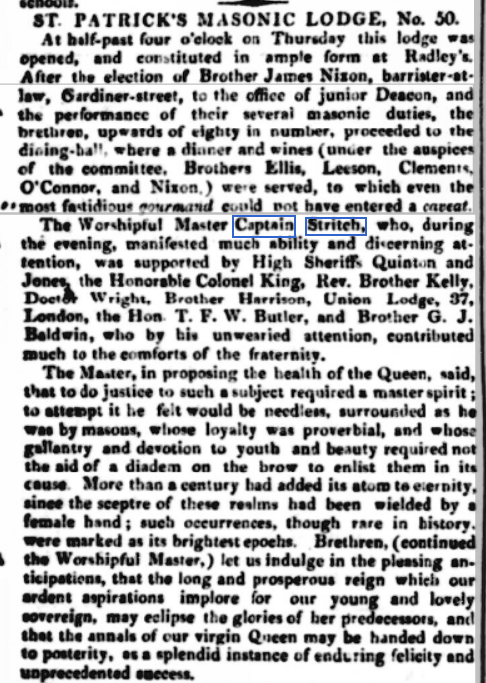

Saintbury is one of the earliest houses to be built in Killiney and its occupant at this time is listed as Captain Stritch in Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary. A Captain (William Luke) Stritch appears in a newspaper report of 1837 in relation to St. Patrick’s Masonic Lodge, No. 50, This lodge held it’s meetings at Radley’s Hotel, College-Green, Dublin. Stritch is referred to as the Worshipful Master of the Lodge in 1837. We have found no other Stritch connection to Saintbury other than this Lewis entry.

Another member of this Masonic Lodge is a Dr. Haliday who was the Senior Warden of the Lodge in 1843. Dr. Henry Haliday also lived in Killiney in Derrynane Lodge, now Glenalua Lodge on Glenalua Road.

It is interesting to note that the road, now known as Kilmore Avenue, which connects Killiney Hill Road and the coast was the only means of access to the Military Battery which was located at the bottom of Strathmore Road where it meets Station Road. It would suggest that the road, probably no more than a dirt-track at this time, was constructed for this purpose originally and only later became a residential thoroughfare.

Prior to the arrival of the railway and the construction of Strathmore and Station Roads the main spine of housing development was limited to Killiney Hill Road which was the only thoroughfare at the time.

Saintbury in 1888

Kilmore House has now been constructed and we begin to see elements like tennis courts, glasshouses and laid out landscaped gardens appearing in the grounds of the Killiney houses.

Saintbury as described by Sheila Mooney, sister of the actress Maureen O’Sullivan, who lived there from 1927 for a number of years.

The extract below was transcribed from ‘A Strange Kind of Loving’ by Sheila Mooney (1990). With thanks to Killiney resident Anne Day for providing us with a copy of the book.

Those are my memories of Bournemouth when Nanny came. Because of the ghost and because my mother was restless and expecting another baby, we moved back to Ireland again. My father’s guardian, The Uncle, died in London and his will left everything to my father, cutting off all the other O’Sullivans. My mother told me we were going to live in a huge house. When we got off the boat at Kingstown, as it was then, we walked up to the Royal Marine Hotel. I said, “Is that our new house?” My mother said it was and I, only five-and-a-half, replied, “Well, it’s not as big as I thought it would be!” We stayed a year in the Marine Hotel while our new home, Saintbury, in Killiney, was being made ready.

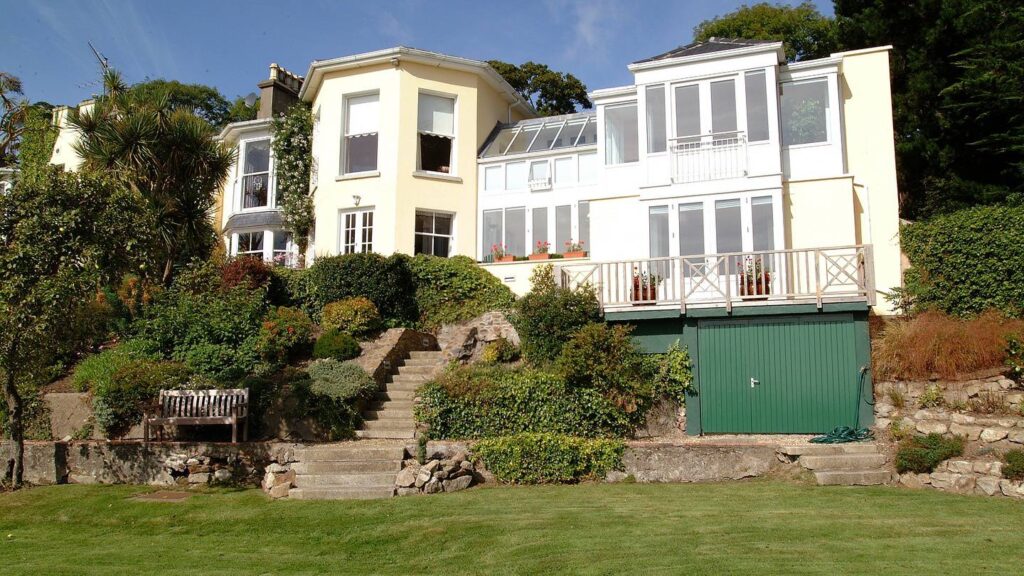

I loved the house the first day I saw it and felt the house loved me. It was a beautiful old house built in 1898, long and sprawling, turreted at either end, nearly 400 feet above Killiney Bay and with a view over the Vale of Shangannagh and the north Wicklow hills. The house was built on rocks so that one came up steps to the hall door. From the front the house looked like an elongated bungalow. From the back it looked like a castle. In summer it was covered in Virginia creeper which turned a beautiful golden red in the autumn. The house stood on four acres and we had a vegetable garden, rose garden, orchard, tennis court and putting green. There was a lovely castellated summer-house and a beautiful plant called lobster’s claw used climb over its portals in July. There were four conservatories for hot-house plants, grapes and peaches. I loved the fernery best. It was cool and green and little frogs used hop around in the moisture. In the front garden were two of the most beautiful willow trees whose branches touched the ground. To a child being under them felt like being inside a green tent.

At the main gates was the lodge where the gardener, West, and his wife lived. He was not the full shilling but he was a marvellous gardener. He worked the four acres of ground, including three large greenhouses. He called his wife “old Louisa Benedictus” (blessed Louisa) behind her back. He was afraid of her but liked to jeer at her. And he did hate Nanny; he thought, be it true or untrue, that she had turned the children against him. He loved us. So as Nanny was English, he called her “John Bull with the big red nose.” We loved it when he shouted this at her! I saw West have a fit once and always hoped he’d have another because he leaped about and shouted and foam came out of his mouth. Then Mrs. West came and took West home. She didn’t speak but put him sitting on down on a hard chair, with his feet in a basin of hot water and a cold cloth round his head. I always wondered how that cured him but it did and nothing was ever said about it. When anything had happened at home, like mother coming in disgustingly drunk or me being expelled from school, it was never mentioned, so that we all began to believe it had never happened.

Opposite the lodge were empty stables (we were all afraid of horses) and the garage with a turn-table for the car. As children we had great fun with this taking it in turns to spin round and round.

My father furnished the house with beautiful things, some carefully bid for at auctions but mostly priceless paintings, silver and antiques from his uncle’s London flat. We had no electricity and the house was lit by gaslight, a much softer light than electric, and there were many lovely oil lamps. Our telephone was of the wind the handle and wait for the operator vintage! My father never got used to it. He always held it well away from him and shouted down the mouthpiece.

Huge antlers and heads of buffalo and antelope and various big game, shot in the Punjab by my Frazer uncles, looked sadly down from the walls in hall- ways. When I was a little girl I used feed these all before I went to bed at night, except the skeleton buffalos which had big black horns and were very frightening. We had an elephant’s foot that gave off such a pong and a leopard skin rug sprawled in the alcove in the drawing-room; it still had its head. I thought it very sad. Some beautiful bearskin rugs- Chinese and Persian-covered the parquet floor as well and there were paintings by Monet, Sir John Lavery and Rubens. At one end of the large drawing- room, where we once danced over a hundred people, the entire wall was covered in an enormous tapestry of a sixteenth century fair and country dance. The lights were particularly beautiful pink and gold shells round the walls. At the top of the big staircase, whose brass stair-rods were polished every week, was a bronze cavalier holding a lamp, while at the bottom stood a reclining nymph holding a shell. The large windows and the very big one overlooking the panorama of Killiney Bay were draped in heavy blue velvet curtains held with gold rope with tasselled ends. My father had his own suite, bedroom, bath- room, smoking-room-cum-library. Here were all his regimental pictures and books and his large picture “Recruiting the Connaught Rangers,” complete with Union Jack.

We all sat in my father’s library because it was the only room with a fire and a wireless set. We only had a fire in the large drawing-room for parties. We were all avid listeners of the wireless set and Jackie, my brother, made a crystal set, a little box with earphones; we thought this wonderful. The large piano-pianola played a big part in my father’s life. This stood in the big bay window of the drawing-room. It was made of beautiful cherry wood, had resonant bell-like tones and was regularly tuned. An equally valuable cabinet contained apertures for all the pianola rolls, operas, Strauss waltzes, even some lighter music. I think I learned my love and, indeed knowledge of music this way. No one could play the pianola like my father. He knew exactly when to play loudly or softly or indeed proudly by pressing the various buttons, soft, loud and fast and slow, so that he with his injured hand could enjoy the music he could no longer play and see the notes moving in time. I would put on my party frock and dance happily; then I felt close to my father.

The Protestant rectory was next door and ours was the only Roman Catholic house that Canon Barker visited! He and my father got on very well in a friendship based on mutual respect. Directly below Saintbury was another beautiful house, Kilmore, home of the late Doctor Bob Collis, born 1900, well- known pediatrician, writer and rugby international. His play, Marrowbone Lane, drew attention to workers’ slave conditions in Dublin. He was keen on my sister Maureen but Hollywood wafted her away when she was only eighteen.

Our family Doctor, Joshua Pim, was three times tennis champion at Wimbledon. Neighbours included Katherine Tynan Hinkson, the poet who is probably best known for “All on an April Evening.” Then the famous Hone family: Evie, Joseph and Nathaniel. Poet and biographer Flora Mitchell (Mrs Jameson) lived nearby also. She wrote the book Vanishing Dublin. Mrs McAteer Parnell, wife of John Parnell, brother of Charles Stewart, lived in Sion House with her sister-in-law, Mrs McAteer. They were very old and wore blonde wigs. They gave a famous fancy dress ball every New Year’s Eve. I went to it much later when I was seventeen, in a Victorian crinoline as “Alice Blue Gown.” Apart from the living, famous shades of those who had passed over remained in the old Killiney mansions. John Millington Synge, 1871-1909, had lived in Glendalough House. John Blake Dillon, 1816-1866, leader of the Young Ireland movement, had lived nearby in Druid Lodge. A Father Healy, 1824-1894, a noted wit, was parish priest in the neighbouring village of Ballybrack. Count John McCormack had lived in Killiney as a young man.

We had quite a nice climate. The influence of the Gulf Stream brought moist air and favoured rhododendrons, fuchsia, blue hydrangeas and palm trees and all manner of semi-tropical flowers. It was said we had the smallest rainfall of anywhere in Ireland. Spring brought an array of daffodils. All that and my interest in the druid circles and ancient church made Killiney for me perhaps the only paradise I will ever know. Sometimes even now I feel my spirit return to Saintbury.

There was a secret passage which was very damp and dark. To get into it, you had to climb through the butler’s pantry over the sink. There was a small white- washed room behind and a cave-like aperture in the wall. The passage went right through the walls of the house and into the garden through a tiny door in a crevice in the wall. Several of the houses nearby also had these passages because at one time Killiney was a great place for smuggling.

The house was so big that we all could live apart. My brother, Jackie, once remarked that, had the house been smaller, we might have got to know each other better. As it was, we all grew up caring very little for each other.

One of my father’s hobbies was clocks. The house was full of them. I used be frightened at night when I heard them striking midnight. A man used come regularly to wind and maintain them. His other great love was the gardens where he spent hours. Because of his paralyzed arm and hand he could not do much except pruning the roses and shrubs. But he supervised everything. The garden was quite famous for its riot of flowers and shrubs and there were always people looking in the gate or asking if they might walk around. How sad for my father that my mother took no interest whatsoever, either in the house or the grounds, though she liked entertaining other Killiney wives to tea-parties held in the big drawing-room. “Damned old snob,” my father called her.

She was always the centre of attention, very amusing, a great and sometimes cruel raconteur. One would hear peals of laughter and know it was directed at some unfortunate guest. I learned how to divert her from this jeering. She would say in front of a crowd of people about me or one of my sisters “the dumplings are boiling over” (we were all well-endowed) and whichever one of us was in question would be scarlet with embarrassment. When she did this, I would throw in something like, “did you hear the awful thing so and so did?” and she would seize upon that and leave me alone. I was the only one who learned how to cope with her and even then not all that much!

My mother had thought there were twenty bedrooms in the house. She was annoyed to discover there were only nine, with big dressing rooms off the two master bedrooms. The servants’ quarters were a large flagged kitchen, scullery and a big larder with cold stone counters. No fridges in those days. The three servants’ bedrooms were off the kitchen. Strict protocol was observed with the servants. Cook, parlour-maid and kitchen-maid, all ate in the kitchen. The charwoman stood in the scullery for a snack lunch. The gardener, if he did not go home to the gate lodge, ate in a shed, known as “the cat house” because Minnie the cat always had her kittens there. Nanny ate in the day nursery with the children and the kitchen-maid waited on the nurseries.

My father used say about Nanny: “that damned old woman never stops ringing the bell.” Nanny entertained other nannies and the children they were caring for. There was great snobbery about who had the best nursery and gave the best teas. The nannies all wore the uniforms of whatever college they had trained in and a badge on their hats. The afternoon walk took about an hour to get ready. A perfect pram, in summer a canopy, a beautifully turned-out baby and an immaculate toddler who had to hold the handle of the pram and walk beside Nanny. Older children were allowed walk in front of the nannies and prams. We were never allowed to run. We, my sisters and I, were always threatened with “I’ll tell your Daddy” and Nanny did tell. A few words from him were enough; he never hit any of us. Mother I didn’t count; she let us do what we wanted. She alternated between making free with the servants and then turning haughty on them. None of them stayed long and my mother was always ringing up the domestic agencies for maids. We had quite a varied assortment and an awful lot of stealing. I remember once going to the large press to get out my summer clothes to find they had all gone!

Our diningroom, like the drawingroom, was large and very cold. The only heating was the one coal fire in the smoking room and the anthracite stove in the diningroom was inadequate. The bedrooms just had electric heaters. The diningroom had a character of its own. It did not seem pretty or lovely like the drawingroom. To me it felt a bit grim. Sour-faced O’Sullivan ancestors stared down coldly and unsmilingly from their ornate frames. It was a little like the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s. Over the mantelpiece was Sir Daniel, my grandfather, in his mayoral robes and on his left my grandmother resplendent in green. To grandfather’s right his father, Cornelius John, with beetling white eyebrows, and eyes that seemed to follow one everywhere. All round the room were these unsmiling faces. It was hard to imagine any of them laughing or having fun.

Suspended over the middle of the long diningroom table was a large red-shaded light. Father sat at one end of the table and my mother at the other. He would pull the shade light down, as he said to my mother, “so that I can’t see your damned silly face.” She was never short of an appropriate riposte. There was really no conversation; all was silent except for the odd belch from mother. The tension was terrible.

My father and mother were both snobs. Everything had to be done correctly. The parlour-maid wore blue until the evening, when she changed into black and white. Because of the constant turnover of cooks, the food was awful. But as long as the table was set properly with nice china and silver cutlery, my parents overlooked a lot. Proprieties were always observed. Finger bowls arrived with the after-dinner fruit. Once a guest drank from his and so did my father to save him embarrassment. We were not allowed gossip with the servants. My father was quite adamant about that; he said that if one got familiar with them they didn’t work as well. I grew up at the end of an era. It was getting harder to find staff and, sadly, gracious living was beginning to disappear.

Records from Thom’s Directory and other sources

| Year | Occupant | Source |

| 1832 | Parker, Frederick S. | Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail 8th December 1832 |

| 1834 | Parker, Frederick St. Bury Esq | Watson’s Almanack |

| 1837 | Capt. Stritch | Lewis |

| 1847-1858 | Allen, Captain Luke | Thoms |

| 1860-1866 | Greene, J. Ball Esq (John) | |

| 1868-1867 | Harris, W. Wallace, Barrister | |

| 1870-1880 | Townsend, Joshua H. Esq | |

| 1884-1894 | Harris, Wm. Wallace LLD TCD Barrister | |

| 1900-1907 | Harris, F.W. Fitzgerald LLD TCD Barrister | |

| 1910-1917 | The above & Harris, Reginald T. MA TCD Bar | |

| 1926 | Harris, F.W. Fitzgerald LLD TCD Barrister | |

| 1924-1926 | Vaughan, Herbert D. Solr and Land Agent | |

| 1927-1954 | O’Sullivan, C.J. | |

| 1960 | Wm. J. Hand | |

| 1975 | J. Hunter |

Images from sales brochures