We, the workingmen of the village of Killiney

We wish to thank Conan Kennedy for contributing this excerpt from his book of the above name which is published by Merrigan Books, 2018.

The back story

“There is no doubt that Francis Edward DuBédat (known as Frank), born 1851, was a man with great charm and presence. He had been a brilliant student at Tipperary Grammar School, excelling in mathematics, and by the time he was a young man, brown haired and blue eyed, he had an enviable dose of self assurance.”

So wrote his biographer, Maria Wooton, as well indeed she might. DuBédat was a banker and a stockbroker, and we recognise his type immediately from our own times, from our own financial leaders, with their own enviable doses of self assurance.

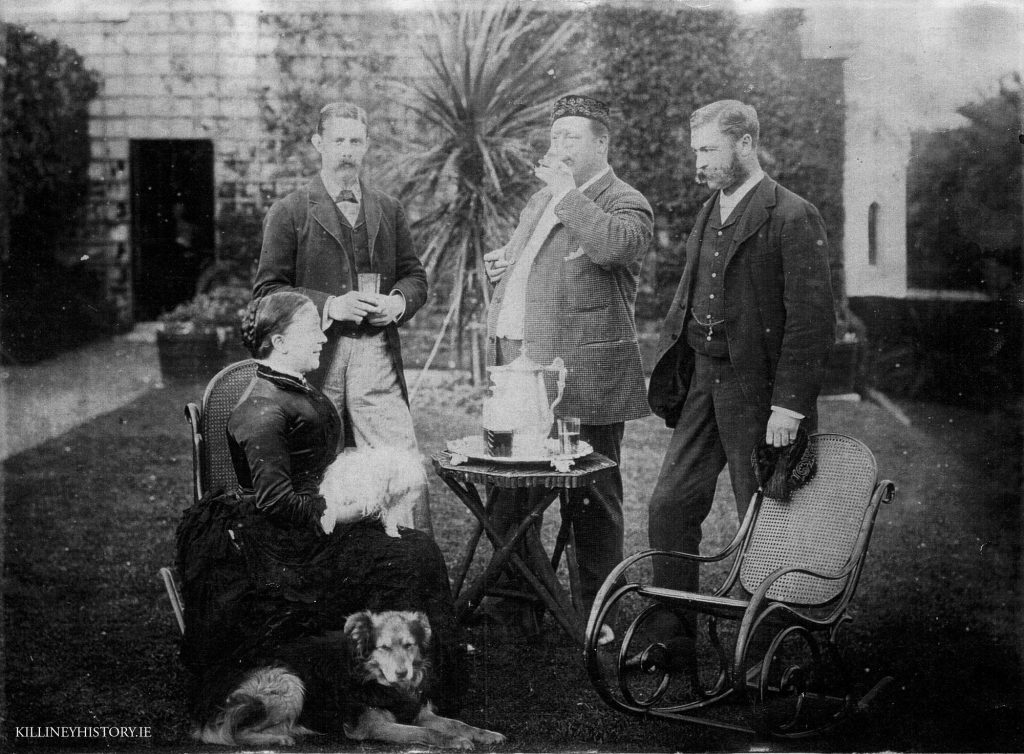

He was well got. Of Huguenot origins, his family had been Dublin bankers and stockbrokers for many generations. Sometimes up and sometimes down, but mostly up, they prospered mightily, owned fine town and country houses, and all was well in their back yard. They are buried in the trim little Huguenot Cemetery in Dublin’s Merrion Row.

But Francis Edward, no, he is buried in South Africa, in the Cape, in a scruffy enough place called Glencairn, overlooking Simonstown Bay. It is a quiet and lonesome spot, typical of many places that shelter dramatic stories in their silence.

DuBédat’s career in Ireland had brought him to the top of the family stockbroking business. He married well, enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, and had built himself a fine house in Killiney. Then, of course, and it seems almost inevitably (being overdosed with self assurance) in 1890 he went spectacularly bust. He fled the country, helped on his way, it must be admitted, by one Frederick Kennedy, a solicitor, who gave him a cheque for £500. Yes this must be admitted because that same Frederick Kennedy was the grandfather of this same writer here. Himself a wealthy man, old Frederick was in turn to hit the financial wall some 25 years later.

But all that… another story.

Francis Edward DuBédat vanished. But not for very long. He was tracked down to South Africa, brought back to Ireland, and put on trial. It transpired that his wealth was based on fraud and Ponzi schemes. The revelations made our modern banking scandals look like the details of a minor traffic infringement. Society was convulsed, convulsed. Ok, let’s be honest, a certain section of society was convulsed. Whether the likes of the workingmen of the village of Killiney were that concerned…the jury is still out. How and ever, Frank’s own jury in Green Street Courthouse in 1891 didn’t stay out long at all. He was sentenced to 12 months with hard labour and seven years penal servitude.

And that…was that?

Not quite.

Frank served four to five years but a mood or feeling gradually grew that he had done enough. Petitions were launched and representations made to the authorities by his family and former business associates. His health had suffered. A few years in the Victorian prison conditions of Mountjoy and then Maryborough (pictured below, now Portlaoise)

could do that to a man. Eventually the pressure on the authorities bore fruit, and Frank was released. After a few months staying with friends in the Killiney/Dalkey area he sailed for South Africa again, there to establish a new life which, his health having obviously recovered, lasted for some 25 years. His health in fact recovered to the extent that he took up with one Rosita Martinez, an actress described as ‘looking as lovely as if she had stepped out of one of Rosesetti’s canvases’. He became involved in new business enterprises and these brought him back to Europe from time to time. During one of these periods, in 1901, Frank and the lovely Rosita were living in Malahide, as ‘man and wife’, safely on the other side of Dublin to that of his actual wife and their children in Killiney.

Now about that wife, and Killiney.

In 1872 Frank had married Mary Rosa. He was twenty and she was… I do not know. But I do know that she was daughter of Samuel Waterhouse, a wealthy gold and silver smith with interests in Sheffield, London and in Dublin. Mary Rosa Waterhouse, known as Rosie, had lived in Killiney’s Glenalua House with her family and, after her marriage, lived in Glenalua Lodge nearby. Her father had property interests over large areas in Killiney, owned several houses and had given his daughter away with a dowry of £3000. None of this had stood in the way of Frank’s rise to wealth and prominence. By 1889 he had been in a position to buy the house then known as Stoneleigh, in Killiney Avenue. He promptly renamed it as Frankfort, and equally promptly embarked on spending other people’s money on architectural improvements and enhancements and extensions to its lands. This enterprise was obviously intended to be a monument to his success. That house is now known as Kenah Hill and the onetime open lands in the vicinity are now Killiney Heath, a place of Los Angeles style houses, garish enough monuments to the success of later generations.

After his years of imprisonment, Frank never did not go back to Rosie Waterhouse, staying instead with the new amour, the lovely and exotic Rosita. The first Rosie, the Irish one, she was in fact to die quite young in 1902, by which time Frank (and Rosita) were established back in South Africa. Yes there had been another legal hitch along the way, Frank standing trial again, this time back in London. Further financial shenanigans, of course, but all was resolved. Frank and Rosita then settled permanently in South Africa, living quietly in Kommetjie.

They had one son, Willie.

Frank died in 1919.

Rosita died in Birmingham in England in 1952.

Willie died in Jersey in 1979.

Samuel Waterhouse died in 1905.

Yes, such neat sentences are the bare bones of genealogy, those of us who dabble know them well. With the likes of Francis Edward DuBédat there is no real difficulty in putting flesh upon those bones. Then as now, Celebs are well known, well got, their stories are in the public domain. It’s not that their stories or their lives are more important, nor even more interesting than others, it’s just that they are available to research, accessible. In fact, when I think, a rare enough occurance these days, when I think about it, the stories of the non-Celebs are actually more interesting, made more interesting by their very unknownness. Is that a word, my proof reader wonders, pencil poised. Unknownness?

No matter, fast forward.

A woman by the name of Mary Bourke from Ballina became President of Ireland in 1990. She had married a Nicholas Robinson. Small world, because this Nicholas Robinson was a descendant of our Samuel Waterhouse above. And thus a President of twentieth century Ireland was related by marriage to a leading fraudster of the nineteenth. And not so many years between them, which shows how fast that things can change, the differences that a few generations can make. And this is where this book is going. I’m interested in a certain cohort of the population of a small village in South County Dublin, a hundred years ago or so. And who they were, and where their descendants are these days, what became of them? It is, if you like, something similar to that tv series, Who Do You Think You Are?

But in reverse.

Who Do You Think You Will Be?

Hard to tell. People and families and generations change, and change is unpredictable. Places likewise. Who would have predicted that the Killiney in the view opposite is the place we know today? Yes, that’s the road down the hill from the village, Bray in the distance and the Martello Tower in the middle. Making sense then, so to speak, with it’s view across the bay. Crowded by houses and trees its location doesn’t make sense today.

But what does?

But the workingmen of Killiney?

As mentioned above, when agitation started for the release of DuBédat from Maryborough Prison, numerous petitions were raised from different interests. These were directed to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and other influential authorities. Frank’s wife Rosa, by then living with her three children in Willmount House, one of her father’s Killiney properties, she wrote to the Under Secretary for Ireland. Loyalty, albeit misplaced, is admirable in a spouse. Her father himself, Samuel Waterhouse, he got in touch with the head of the General Prisons Board. And a long list of members of the Dublin Stock Exchange presented a ‘humble’ memorial to His Excellency The Right Honourable Earl Cadogan, Lord Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland. The humble memorialists prayed that your excellency will be pleased to commute the remainder of DuBédat’s sentence. Interestingly, several of the humble signatories to this lickspittle effusion bore names well known in Dublin stockbroking circles even up to our own quite recent times. Dudgeon, Bewley, Bloxham, Goodbody. It seems that life in Ireland is a sluggish enough stream, and little changes. Except nowadays our great and good tend to contact Brussels when in search of favours?

No doubt, no doubt at all. Petitions back in the day were what we now call lobbying, which some describe as a multi mega industry of institutionalised corruption, but be that as it may. The particular Petition that interests here does not come from influential and powerful interests of Victorian Ireland. This one emanates from a different source entirely. Yes it is directed, upwards, via an influential person, but comes not from members of the influential classes.

To the Right Honourable John Morley, Mount Eagle, Killiney

On behalf of

Mr Frank E. DuBédat.

From the workingmen of Killiney village.

Right Honourable Sir –

We, the workingmen of the village of Killiney, humbly pray that you will use your great influence with the Government, to bring about the release of the above named gentleman from prison. He is now after serving a long term of imprisonment for misdemeanour and we sincerely hope that you will see your way towards tempering Justice with mercy, and restore to his sorrowing family a gentleman who was ever Kind to the poor, and loved by all. Do this act of mercy, and you will ever have the gratitude of the undersigned.

Michael Fanning, Thomas Buggle, James Kelly, John Bryan Jnr, Mark Timmons, John Devine, William Mullen, Patrick Fanning, Peter Mason, John Ryan, John Bryan Snr., Phelim Redmond, Charles Dignam, William Lambert, Patrick Reilly, Patrick Casey, Charles Hall, James Hall ,William Holley, John Byrne, Henry Murnane, Michael Dowd, Christopher Murdock, Daniel Casey, Michael Bryan, Martin Byrne, John Cunniam, James Keily, James Richardson, James Colclough, James Horner, William Fanning, Michael Fitzpatrick, James Ryan, Laurence Reilly, Edward Coyne, Laurence Leary, Phillip Cashion, John Woods, Nicholas Slack, Francis Stack, William Hall, George Hall, Patrick Murdock, Thomas Smyth, John Trevors, Peter Dowd, Patrick Dowd, Andrew Murdock Jnr., Thomas Prendeville, Thomas Kavanagh, John Cunniam, Michael Quinsey, Patrick Cowper, Thomas Cowan, Daniel Healy, Nicholas Nolan, Kevin Grattan, Thomas Neale, Matthew Redmond, John Stack, James Lalor, Michael Bryan Jnr., Thomas Kennedy, Richard Homan, Richard Redmond, John Murdock, Martin Hughes, William Cashion, Thomas Haughton, Thomas Hughes, Dennis Murphy, Andrew Murdock Snr.

And about those ‘undersigned’.

It does appear that those names, described in the petition as undersigned, are, apparantly, nothing of the sort. DuBédat’s biographer, Maria Wooton, who unlike this writer has had sight of the original document, she points out that the names are not signed individually, but rather are all written in the same hand. Be that as it may, the names are there. The actual mechanics of getting them on the paper are lost to history. Of the intermediary, the Right Honourable John Morley of Mount Eagle, I know not. Could that be the same Rt Hon who was Chief Secretary for Ireland in the 1890’s? Or could he indeed be an ancestor of the Mr Morley the builder who built Ard Mhuire Park off Dalkey Avenue in the 1950’s, who’s eccentric brother lived in a now demolished cottage at the top of Killiney Road, wearing a straw boater in all weathers, watching? Could be, possible. What’s definite is that Mount Eagle is a grand house in Vico Road, splendid, though in modern times one that seems to feature rather too often in planning and financial controversies.

Whatever about all that, petition-wise, there can be no doubt that the whole thing was orchestrated by those in charge of the general campaign, and equally no doubt that it may not have been politic for workingmen to refuse their names. As becomes clear in the following pages, many of the signatories were actually working directly for the wealthier classes in Killiney, and likely to be living in lodges and cottages owned by their employers. It would hardly have been sensible to have refused their name. Perhaps indeed DuBédat was considered ‘a decent man’, many Irish rogues do gain that appelation among the generality, and equally perhaps he was generous and charitable. Many Irish rogues are likewise to this day. Be that as it may. The truth is likely that people didn’t care much one way or the other. A Petition was going around. Perhaps right there behind the bar of the Druids Chair Pub in Killiney.

“Have you signed the Petition?” asks the barman.

“Not yet,” says the customer, “give it to me here. And while you’re at it… put me on another pint”.

This is the way it likely was, though of course that particular exchange might well have occurred down in The Igo Inn in Ballybrack. None of that concerns. This is not a sociological analysis of the ins and outs of Killiney affairs in the 1890’s. This is a modern writer sitting here with a list of names, and wondering who they were, and about the details of their lives. And what became of them, their children and descendants. On top of which this is a writer sitting here who was actually born not half a mile from Killiney Village, and thus a man with a personal interest. And the purpose of this exercise is to investigate some of his fellow Killiney folks, and learn, and tell.

So let’s turn the pages forward.

That always tends to turn the pages back.

Talking of which…above is a sketch of Cottages in Killiney. From the earlier part of the 19th century, the artist Henry Brocas died in 1837, so that was years before the days of which I write. But somehow one has the feeling that in the intervening…well…not that much had really really changed.

MICHAEL FANNING? Of him I find no trace.

THOMAS BUGGLE was a 47 year old ‘gardener’, an occupation classified in the 1901 Census as ‘domestic servant’. Yes, I do mean the 1901 Census, which I have had to use to get the basic information on individuals. Remembering that the Petition was prepared in 1896, we calculate five years have passed since Thomas gave his name. He was thus in fact only 42 at petition time, and moving on through the names we may mentally similarly deduct five years from all the ages given in all of this listing below.

Just remember Wordsworth.

Five years have passed, five summers with the length of five long winters.

That’ll help.

Born in Kildare, Thomas Buggle was married to Annie from County Down. They lived in Upper Killiney Road with daughter Alice, a dressmaker aged 21 (in 1901 !), and their 18 year old (in 1901 !) son Patrick, who had the same occupation as his father.

JAMES KELLY was a 60 year old ‘agricultural labourer living in the Rathmichael townland of Tilly Town. He was also a 40 year old ‘labourer’ living in Loughlinstown. This is where genealogy gets frustrating. They both lived close to Killiney, and both had the occupations one would expect.

Read more about Frank DuBedat here

The book with all the listings is available from the website conankennedy.com