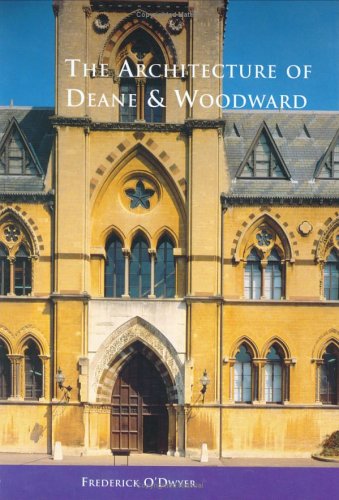

Extract and photographs from ‘The Architecture of Deane and Woodward’ by Frederick O’Dwyer, 1997.

The only reference to Deane and Woodward’s domestic works to be published in the columns of The Dublin Builder appeared in the issue of 15 February 1861. In a piece on house building in Ballybrack, County Dublin, the writer referred in passing to six new dwelling houses being built to their designs, including one for Joseph Robinson, ‘the eminent opera singer’. The foundations had been laid out and the tone of the article suggests that the writer simply made a tour of the many sites in the vicinity and made enquiries from the workmen. Only four Deane and Woodward houses can be identified and it is likely that the writer erroneously included in his tally two neighbouring houses, possibly designed by George Wilkinson (c.1813-90). The reference in the same article to two houses in the course of construction for Mr Boyle is ambiguous, but in fact refers to a development some distance away, unconnected with Deane and Woodward, whose houses are not in Ballybrack proper, but on Killiney Hill.

The development of Killiney in the 1860s transformed a barren hilly stretch of coastline into Dublin’s most fashionable suburb. Those familiar with Killiney today, with its well-planted gardens, abundant shrubs and mature trees would find it hard to recognise photographs of the area when its rocky slopes had little cover other than gorse and the new houses stood out against a backdrop more reminiscent of California than Dublin. Halfway up the summit of Killiney stood the dramatic pile of Victoria (now Ayesha) Castle, from whose ramparts one could view the sweep of Killiney Bay and the Sugarloaf mountain beyond. The similarity with the panorama of the Bay of Naples is recalled in such names as Sorrento Terrace and Vico Road. Victoria Castle and the nearby villa Mount Eagle were built (c.1837-40) by the local proprietor Robert Warren, apparently from the designs of his nephew, the architect Sandham Symes (1808-94).

In 1844 Brunel’s atmospheric railway linked Dalkey with the Dublin to Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) line. By 1854 it had been replaced by conventional track and extended southwards along the coast to Ballybrack. The section to Wicklow was opened in the following year. Warren could now embark on a second development, on a less grandiose scale, and in 1857 he offered for sale a piece of land on the slopes below Victoria Castle, employing the engineer Joseph Lee to draw up a map which he then had lithographed. The purchaser was Joseph Hone (1804-65), solicitor and elder brother of Thomas Hone, on whose ground Balnootra [qv] was built. A plan (now in the National Library of Ireland) was drawn up by Wilkinson, showing suggested villa building lots. Hone built two adjacent houses South Hill and Palermo (as well as nearby Temple Hill for himself), but sold an adjoining three-acre site to Robert Exham (b.c.1810), the Cork-born wine merchant, in 1860. Exham’s father had witnessed the sale of the Dundanion estate to Sir Thomas Deane in 1823. His uncle was acting secretary of the Cork Savings Bank during the period of Deane’s trusteeship.

Exham decided to divide his site into three plots, retaining one for his own use and selling leases in the other two, with the stipulation that each house should cost a minimum of £1,500 to construct. The purchasers were Joseph Robinson, conductor of the Antient Concerts Society, and William Bewley, a Dublin merchant. Robinson’s brother Francis bought a site directly from Hone, which lay to the south-east of the others, separated by a road and bordering the railway. There was a minimum cost stipulation, again of £1,500 and an option, not exercised, to halve the plot of almost two acres and build a second house of similar value. Deane and Woodward were engaged as architects for all four houses. They had been employed at the Antient Concert Rooms in 1859, of which Exham and T.N. Deane’s brother-in-law Joseph Manly were committee members.

The leases between Hone and Exham, Hone and Francis Robinson, and Exham and Joseph Robinson all commenced on 1 November 1860, although they were signed in the following year. Bewley’s house Illerton (now called Alloa) is later than the others, dating from 1863 to 1864. The most successful architecturally is Francis Robinson’s Undercliffe, undoubtedly Woodward’s work and the apparent prototype from which the others were derived. The lease of Undercliffe was the first to be registered, on 13 February 1861, and it seems likely that it was also the first house to be started. Joseph Robinson’s Green Hill (now called Cliff House) and Robert Exham’s own Fernside were not begun until early in 1861. The Dublin Builder article indicated that the foundations had been laid out by 15 February. However, arrangements were clearly being made before Woodward’s final departure for the continent in mid-December 1860. Benjamin Patterson, Deane and Woodward’s quantity surveyor, records that he visited the site with Exham on 18 November 1860. Patterson marked out the boundaries of the house sites on 31 December. Tenders were invited for the houses on 8 January from Messrs Douglass, Cockburn, Millard and Beardwood. On the following day Patterson engaged Henry Madden to prepare the site and lay out the avenue, since the ‘houses were to be commenced immediately’. Patterson certified an interim payment to him on 14 February 1861. He had made copies, for tender purposes, of the bill of quantities for Exham’s house on 15 January 1861. The contract for the two houses was awarded to James Douglass, who also built Undercliffe. He was later to build Deane and Woodward’s church at Rathmichael, County Dublin. Fernside and Green Hill had been completed by May 1862 when they are referred to in an agreement made between Exham and John Shaw, a Belfast merchant. Undercliffe makes its first appearance in Thom’s Directory in the same year.

The area must have been familiar to Woodward; his aunts, the Misses Jane, Eliza and Sarah Atkinson, had rented Firgrove, near Ballybrack village, since 1848. He could have carried out the basic design work on the three earliest houses in the summer and autumn of 1860.

The Killiney houses are all finished in stucco or dash, with stepped brick arches, brick dressings and the occasional limestone shaft and carved capital. They are smaller in scale than the granite-faced villas of 1858 and lack the elaborate door frames and fretted balusters of the grand designs. Like the wood-work, the chimney-pieces were probably provided by the builder, rather than designed by the architects. Nevertheless, the geometrical planning and arrangement of the facades more than compensate for the loss of such trimmings. Woodward shows that he could create a successful design to suit a relatively tight budget. One recalls Rossetti’s comment that the ‘chief characteristics of Woodward’s genius as an architect were elevation and harmony in the whole’.

UNDERCLIFFE

Undercliffe, like its neighbours, was built on sloping ground so that the basement was split-level and lit only from the garden front. The only level part of the site was the driveway, which was parallel to the road (Strathmore Road), and that is partially on made-up ground. The plan is basically L-shaped, with a triangular porch inserted between the arms. The granite architrave is similar to those of internal doorcases in the Kildare Street Club. The upper walls are supported on arches springing from a central column in the angle in the entrance hall. The secondary stairs is in a turret and joins the main staircase at a half-landing, lit by a characteristic triangular dormer. The fanlight over the front door is also triangular. There is a second turret on the garden side. The drawing-room and dining-room are at right angles to each other, a characteristic of Woodward’s houses. Each connects to an intercommunicating lobby in the turret, which in turn is surrounded by a balcony. Two of the bedrooms, on the first floor, also had balconies, one of which—around the turret—was extended in reinforced concrete along two sides of the house in the 1970s (an attempt was made to match the old work in detailing the extended balcony and balustrade). The staircase from the drawing-room to the garden is a concrete replacement of a timber original. The chimneystacks were rebuilt in the 1930s, but differ from their predecessors in detailing only; Victorian-style pots were affixed in 1996. The triple-arched dining-room windows, with their tall shafts, are also derived from the Kildare Street Club. The capitals here and throughout these earliest three houses have naturalistic carvings.

FERNSIDE

Robert Exham’s Fernside is larger than Undercliffe, having been extended within a decade or so of its erection by an addition at its northern end. It is basically a rectangle, but with numerous splays and set-backs reflected in an amazingly complex, yet turretless, roof line. The approach from a private avenue, which also serves Illerton and Green Hill, reveals a dramatic ascending series of roofs. There are corresponding changes of level on the first floor. The house is divided horizontally by a corridor and principal stairs, lit from the north. Accommodation on the entrance side is ancillary, the cloakrooms and back stairs requiring relatively low ceilings, while the principal reception rooms on the garden fronts push the bedroom floors up another half storey. The original of the two three-storeyed bows on the east elevation is rectangular at basement level, enabling french doors in the angles above to open onto balconies.

GREEN HILL

Joseph Robinson’s Green Hill is a cross between Undercliffe and Fernside in that it has a turret and a projecting bow. The turret is placed in the angle of the drawing-room wall. One of the chimneystacks is placed at a 45 degree angle as at St Austin’s Abbey, while the entrance has a Gothic arch, instead of the low door and projecting canopy of the first pair described; the only full-blown Gothic opening in any of these houses, it was executed in Caen stone with a brick archivolt. It is a little disappointing to find no corresponding feature internally, the quatrefoil and circular lights in the tympanum being set into a flush wall just below the ceiling.

ILLERTON

William Bewley’s Illerton is probably by T.N. Deane rather than Benjamin Woodward and does not appear in Thom’s Directory before 1864. Bewley purchased the site from Exham in 1863, the boundary having been laid out by Patterson in January of that year. The elevations and chimneys have a liberal sprinkling of Jacobethan ornament. The porch is probably original, though it looks like an addition. The kitchen and servants’ quarters are separately articulated under a straightforward, and relatively low, hipped roof, a feature common to Green Hill and also found in Glencairn. There is a characteristically detailed veranda and at right angles to it a conservatory with a curved roof. Green Hill and Fernside had similarly detailed, but free-standing conservatories. In the garden of the latter there is also a rustic hut, probably original. Illerton was the only house with an attached stable-block, a substantial structure with its own yard. Its neighbours had their stables on the north side of the avenue. The avenue entrance was flanked by piers of unexceptional design set in front of a plain gate lodge, with a curious triangular bay window, derived from Clontra, and giving the keeper excellent views up and down the drive. In 1862 the Antient Concert Rooms were sold. Within a couple of years the Society itself had ceased; it last appears in the 1866 edition of Thom’s, with Exham as honorary secretary and Joseph Robinson as a committee member. Robinson had resigned as conductor in 1864. By 1866 he had left Killiney and had gone back to his town house, 3 Fitzwilliam Street Upper, which he had first occupied in 1857. Francis Robinson continued to live at Undercliffe until 1871, the year before his death. It was later the summer home of the Right Honourable Edward Sullivan, master of the rolls. In the twentieth century Undercliffe was occupied for a time by the family of the academic and writer Enid Starkie, whose autobiography describes her childhood there; while Illerton was later the home of the artist Flora Mitchell. In 1871 Robert Exham built a large classical house of little architectural pretension, called Kenah Hill, about a quarter of a mile to the west of Fernside.

COURT-na-FARRAGA

Exham’s brother William Allen Exham QC (1820-81) came to Killiney in 1865 and occupied Kilmore House until his own new villa, Annaghnoon, was ready for occupation in 1869. He soon renamed it Court-na-Farraga, from which its present title, the Court Hotel, is derived. Court-na-Farraga is much larger than the earlier houses and can be attributed with certainty to T.N. Deane. It is Jacobethan throughout, with shaped gables and applied decoration in which the traditional strapwork ‘X’ serves also as Exham’s monogram. The elaboration of detail does not disguise its ancestry and many features of Undercliffe, including the turret, occur also at Court-na-Farraga. The lead canopied regency style veranda, which graced the south elevation and the red brick gatehouse, no longer survive. Additions, including a second turret, were built in 1973. The original house is now somewhat dwarfed by further extensions of the 1980s.