Introduction

This article pulls together a selection of articles and stories which we have compiled over the past two years from a variety of sources and which are all related to the history of Killiney Strand. We are very grateful to the numerous contributors and we hope that the selection presented here provides an interesting overview of the Strand from 1760 to the present day. There may be a small amount of duplication but it was important to retain as much of the original text as possible. Many of the pieces and some of the images have never been published before and there are a few surprises and a few laughs to be had below, enjoy.

Earliest evidence of bathing activity on Killiney strand, 1760

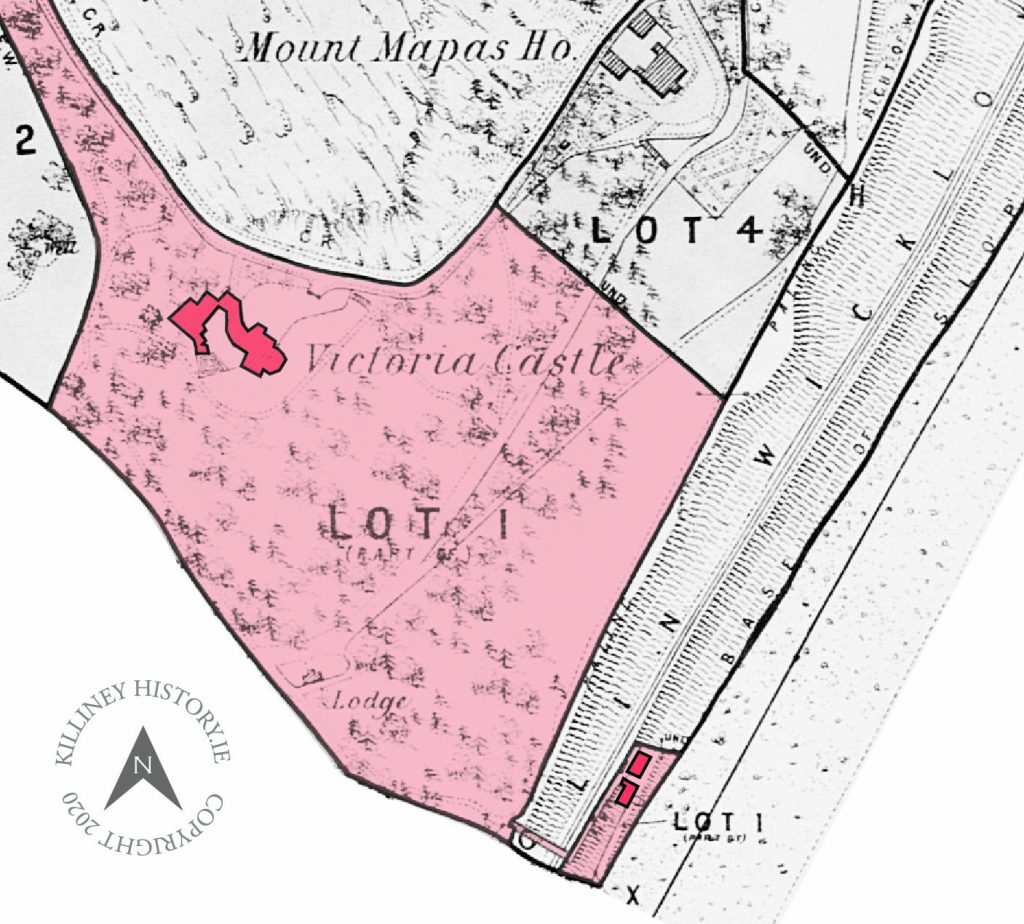

John Rocque’s map of 1760 indicates a Bath House on Killiney beach in the same location as the property now known as the White Cottage. This bath house was on the property of the nearest house of significance which was then called Roxborough (now Killiney Castle Hotel). This was the residence of Captain Edward Maunsell, High Sheriff of County Dublin at the time. It would appear that the Bath House was accessed via the walled enclosure to the grounds of Roxborough which property extended to the shoreline at each extremity. This private facility would have provided exclusive changing and bathing facilities to the residents of Roxborough and their guests. The size indicated on the map suggests that this was a large building or complex of buildings, possibly not dissimilar to what exists at this location today. The beach access provided was obviously a major attraction to the fortunate occupants of the property and the link to the house and its continued use can be traced further to 1872 when Victoria Castle, which was built on the Mapas estate in 1840, was given access to the facility to enhance its attraction to would-be residents who could avail of renting the property for the summer season. When the property was put up for auction in 1872 the descriptive particulars stated that ‘this Lot has convenient access to the sea and a bath-house on the strand.’ The occupant had the right to use the bridge over the railway to access the strand and was also entitled to ‘gather and carry away all the sea weed cast in by the tide on that part of the foreshore.’

Robert Mallet and Seismic experiments on Killiney beach in 1849

Extract from An Irishman’s Diary. By Leo Enright Sat Jan 6 2007

If a man detonated a 12-kilogram bomb on Killiney beach in south Dublin you might expect him to attract some public attention. If he then planted half-a-dozen of these improvised explosive devices on Dalkey Island and blew them up in sequence you might even expect a degree of public opprobrium, if only out of concern for the King of Dalkey’s goats.

And if that same man then travelled to Wales under the banner of an organisation called the BAAS and detonated six tonnes of high explosive, there would surely be huge public interest, not to say outrage, back home in Ireland.

But no. For few people in this country have ever even heard of Robert Mallet. Yet his explosive exploits around Killiney and its environs are the stuff of legend among the peoples of the regions of Basilicata and Campania in southern Italy, because Mallet’s Dalkey detonations are credited with helping to save innumerable lives in the cities and towns of Italy and around the world.

Mallet, an Irish civil engineer, was the father of the modern science of “seismology” – a word coined by him in 1858. Born in Dublin in 1810, he graduated from Trinity in 1830 and by the age of 22 was a member of the Royal Irish Academy. He was an early member of the Civil Engineers Society of Ireland.

His interest in causing explosions arose from his reading of Charles Lyell’s seminal work Principles of Geology. He was enthralled by the idea that geological events were governed by scientific laws and he set about applying his engineer’s knowledge of mechanics to the interpretation of earthquakes. His problem was that there were not too many earthquakes in Ireland; so he set about making his own.

With funds from the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Mallet embarked on his bombing campaign during 1849 and 1850. He set off his first 12-kilo charge on Killiney beach at a depth of two metres, one-and-a half-kilometres from his detector. Shock waves travelled slowly through the damp sand of Killiney, whereas on Dalkey Island the hard granite rock transmitted the waves almost twice as fast.

His work was greatly praised by Charles Darwin and other scientific notables of his day. Most strikingly, he was able to apply the brilliant insights of his fellow Dubliner Sir William Rowan Hamilton: he showed that Hamilton’s mathematical description of the way that light beams reflect inside crystals could be adapted to the motion of seismic waves within the Earth.

Leo Enright is a member of the governing board of the School of Cosmic Physics at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Interviews with Ken and Susan Homan

In her book ‘From Dirt and Dips to Dryrobes’ (2021), Eileen O’Duffy interviewed Dalkey residents Ken and Susan Homan whose family connections with The White Cottage go back many generations. (With apologies to Eileen I have combined my notes of a more recent conversation with Ken and Susan with Eileen’s published interview of 2021.)

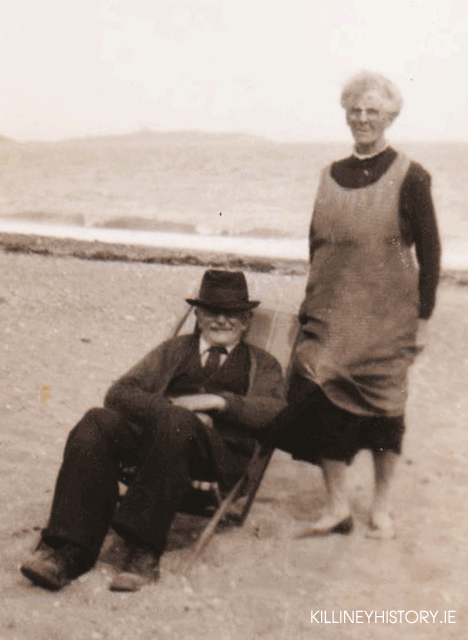

Ken Homan was born in 1931 and was reared in The White Cottage along with his brothers and sisters. His grandparents, Richard and Helena also lived there. Ken’s parents, Fred and Margaret, organised dances which continued there until the early 1960’s. At a later stage, Ken’s brother, Fred junior, and his wife Nancy took over The White Cottage.

The Homans originally came from Delgany in County Wicklow. Helena came as a nanny from Karlsruhe in the state of Baden-Wurttemberg in Germany. She was 16 when she came to work for the Lloyds who lived in Victoria Castle. Helena married Richard Homan who is Ken’s grandfather. He was a fisherman who caught salmon and cod. Ken recalls the stories about Helena teaching the children to swim on ropes. She was in charge of the bathing boxes and looked after their upkeep and collected the rental money. Ken, who is now in his nineties, recalls that men were not allowed on the beach until after 4pm, before that it was strictly for ladies and children. Helena also taught ballroom dancing in Dalkey Town Hall. She was 91 when she died in 1943 so she would have arrived in Killiney in about 1869. She was born in 1853.

They recall there was a bath-house next to The White Cottage which was for the exclusive use of the residents of Victoria (now Ayesha) Castle which had a private right-of-way leading from the castle to the beach. It was a single storey building (now a three storey home) with a boiler and two large bath tubs -one for women and one for men- but the men and women had to take baths on different days of the week. Ken remembers that a maid would come down from the castle and call Helena Homan to prepare a bath. Helena would then gather seaweed from the beach and prepare a hot seaweed bath for a member of the Ayesha Castle family, the Lloyds.

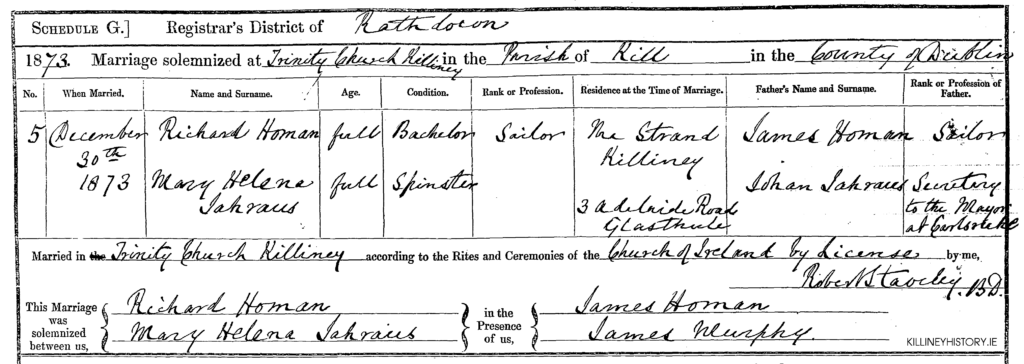

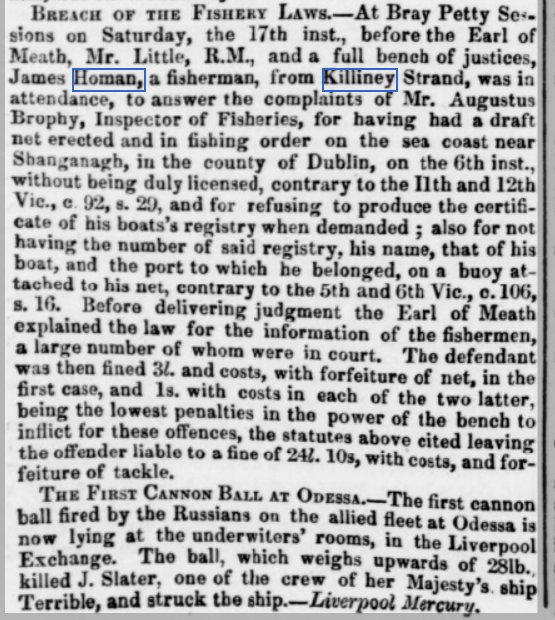

Mary Helena Jahraus who married Richard Homan, Sailor of The Strand, Killiney, was the daughter of Johan Jahraus, Secretary to the Mayor of Karlsruhe (formerly spelled Carlsruhe in English) in the state of Baden-Wurttemberg in Germany. She had been living at 3 Adelaide Road in Glasthule prior to her marriage. Richard’s father was James Homan, also recorded as Sailor. We assume this is the same James who is mentioned in the newspaper report of 1854, below. Richard and Helena were married at Holy Trinity Church, Killiney on 30th December 1873. Richard died on 9th June 1908 aged 63. Helena (Mary Helena Homan, widow of fisherman) died at The White Cottage on 30th November 1943 aged 91.

Before Susan and Ken met their families had already being having dealings. Susan came from the Atkinson family of boatbuilders in Dalkey who had built a motor-launch for the Homans. This boat was called the ‘Evian’ and was used for pleasure cruises around Dalkey Island and the bay. It turned out that many years later, after it had been sold, Ken and Susan were on holiday in Foynes and came across this very boat. The ‘Evian’ had ended up in service bringing people to and from the flying-boats from the US which were stationed there around the time of the war. The Atkinsons also built the ‘Geraldine’ which ended up being torpedoed in Scotsman’s Bay during WW1.

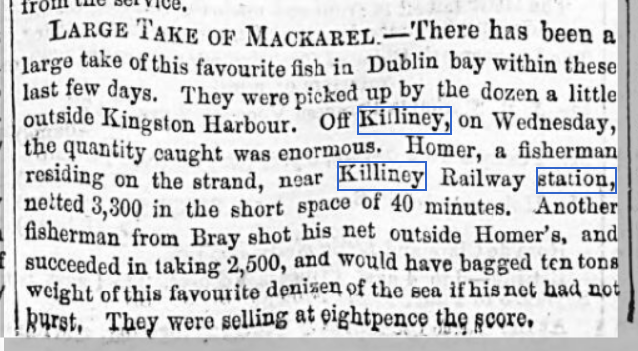

Earliest mention of the Homans of Killiney Strand, 1854

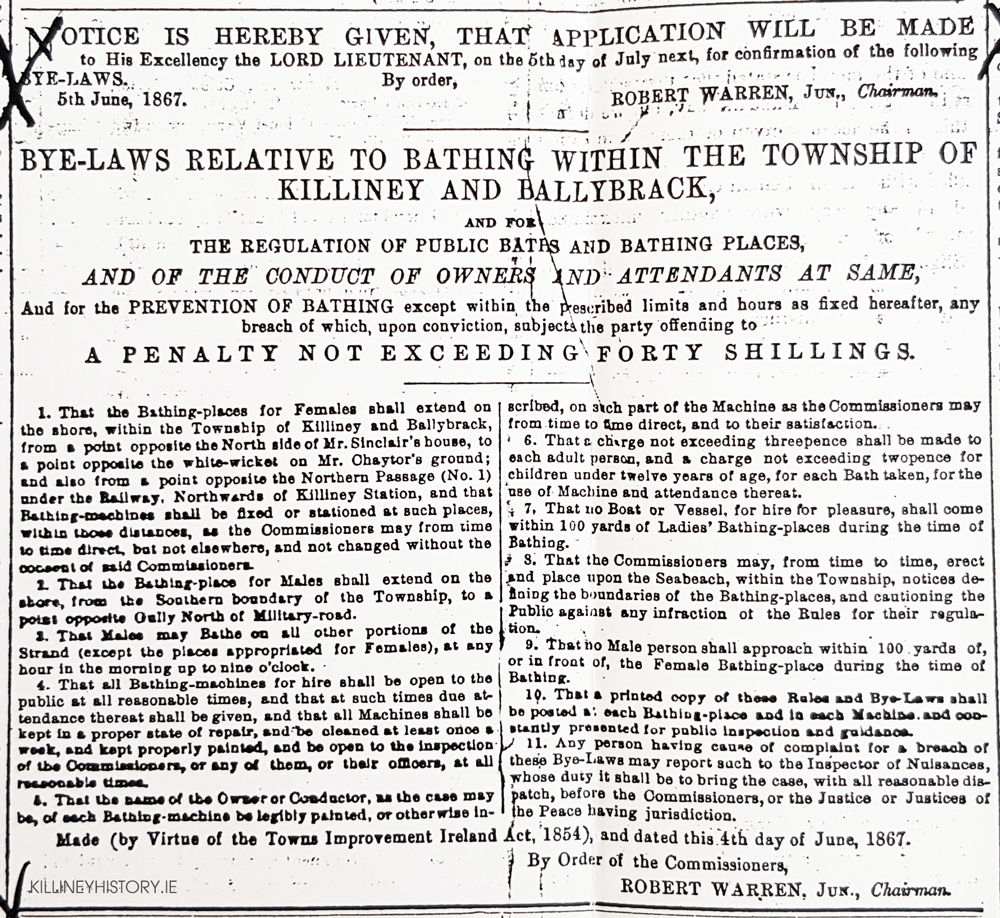

Bye-Laws of 1867 Relative to Bathing within the Township of Killiney and Ballybrack

The newspaper notice of 1867, below, stipulates that the female bathing place extended ‘from a point opposite the North side of Mr. Sinclair’s house (Miramar) to a point opposite the white-wicket on Mr. Chaytor’s ground’ (Marino). It goes on to mention that ‘Bathing-machines shall be fixed or stationed at such places, within those distances, as the Commissioners may from time to time direct’ This is the only mention we have so far encountered in relation to the possibility of mobile Bathing-machines on Killiney beach. Certainly fixed bathing boxes were widely used but no photographs or paintings from this era show bathing-machines, although they were in use in Dun Laoghaire at some point. The very strict rules in relation to the control of access to the ‘Ladies Bathing-places’ go on to state ‘That no Boat or Vessel, for hire for pleasure, shall come within 100 yards of Ladies Bathing-places during the time of bathing’ The regulations to preserve the modesty of the female bather reflect the general attitudes of the time.

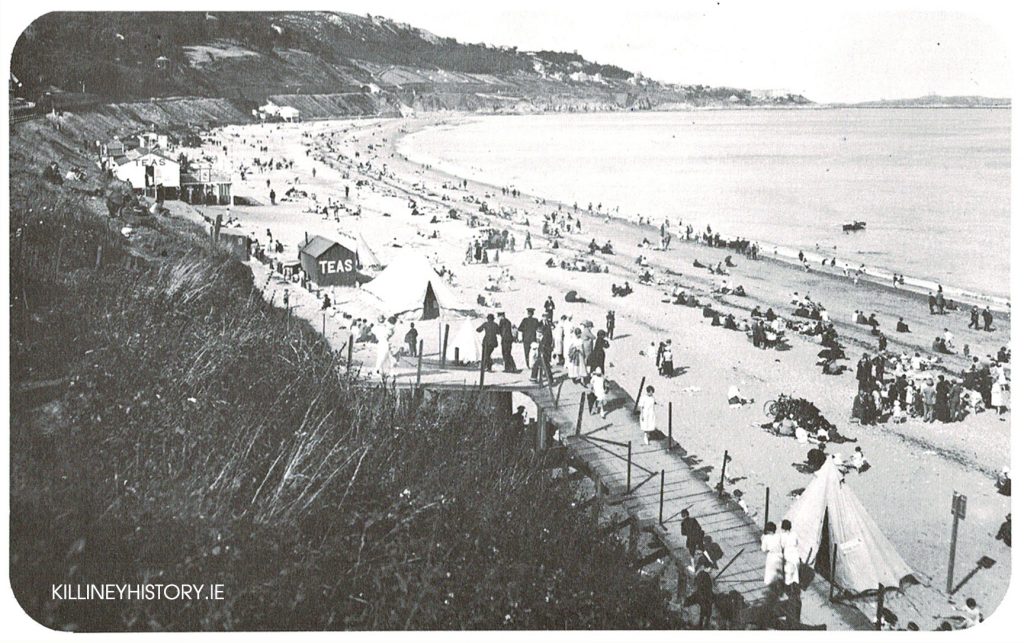

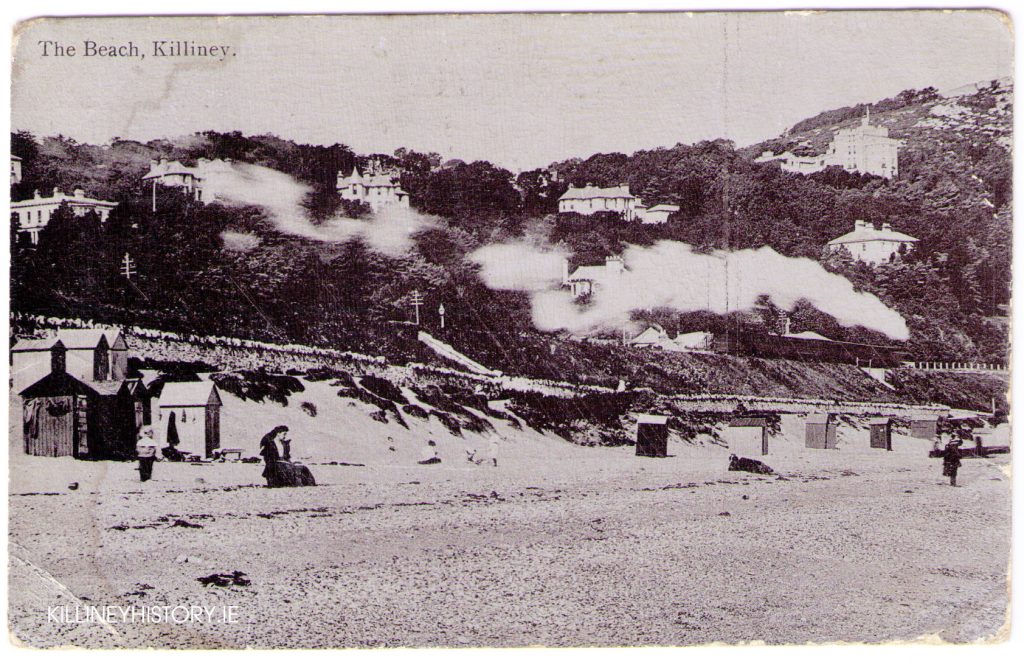

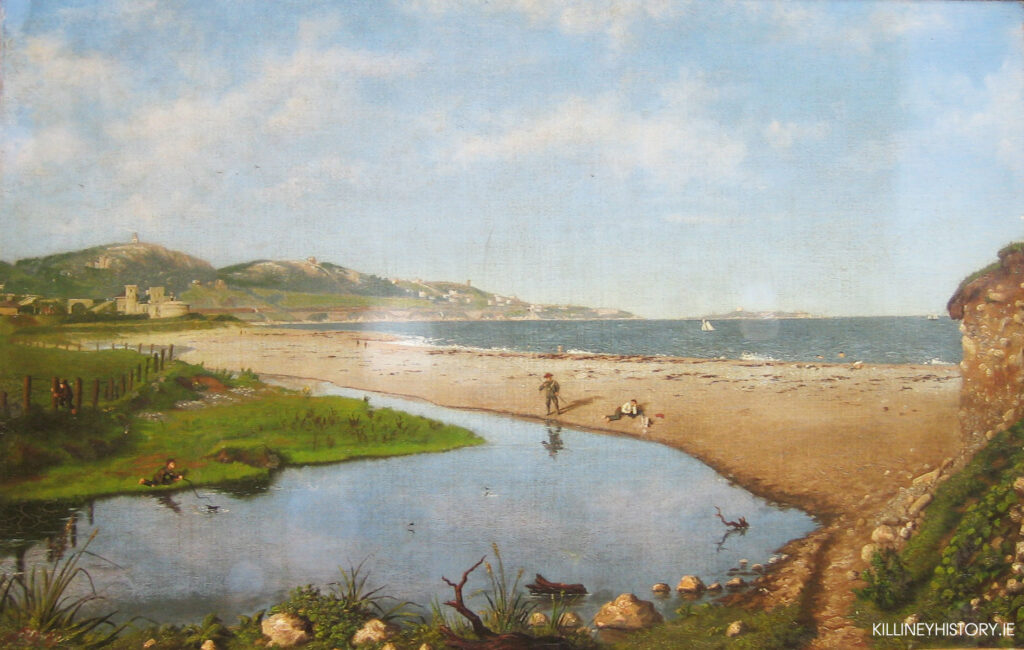

Some early images of Killiney Strand

Reminiscences of Miss Rambaut who lived in Templeville, Killiney Hill Road c.1930

By Miss Rambaut of Templeville.

Text courtesy of Anne Peters & David Millar from an unpublished collection of essays compiled by William Fernsley Figgis (1884-1956) called ‘Killiney Surroundings’. W.F. Figgis lived in Desmond (now Padua) on Killiney Hill Road from 1940 -1952 and previously in ‘The Whins’ now ‘The Rocks’ on Glenalua Road.

The beach was divided by unwritten laws into separate parts, the north end beyond the White Rock belonged to the male bathers, the south end to people who lived in the castellated houses, while the middle portion, the best and safest, was reserved for ladies and children and ruled over by the revered Mrs. Homan whose will was law. To her belonged half a dozen bathing boxes, to her belonged many strange garments of various sizes. These she spread out in the sunshine. From afar off could be seen the ample proportions of her figure. There was the tunic, made of navy blue serge trimmed with white braid, encircling it the 45″ long belt and beneath it, the dismembered other portion which clothed the lower limbs from waist to ankle.

Close to the bathing boxes were to be seen curious shirt like garments drawn in round the neck by a string. These on a windy day appeared very unreliable and inadequate to those of our nurses who were of a decorous character.

Mrs. Homan, tall and quaint with a voice shrill as that of a seagull, wearing a poke hat moored to her chin by a red handkerchief, skirt reefed up over a short petticoat, would stand at the edge of the waves with half a dozen light ropes in one hand while with the other she waved instructions on the art of swimming, threatened those who refused to wet their curly pates or draw to land naughty ones who refused to come in when commanded. Her ropes were tied round fat little waists of the small children who were without a nurse or governess and woe to those who stayed too long either in the sea or in the bathing box…. I do not know what relation Mrs. Homan was to Mr. Homan; dear darling wonderful Mr. Homan, who when turned out of his house by an angry wife, just went and lived in 2 bathing boxes joined together and heated by a kind of little charcoal stove with a short black pipe as a chimney. In this. delightful house he had a bed with a white and blue blanket, a patchwork quilt and a shelf on which was a brown teapot, a cup, a saucer which did not match the cup but was the same colour as the milk jug, a loaf of bread and a beautiful blue bag of sugar. There was also a frying pan, a kettle and a black bottle, a store of shells and often a quaint creature like a mermaid or a starfish in a bowl for his children and friends. Mr. Homan had the bluest eyes, the longest white beard and the reddest/largest nose ever seen. In short, he was a most wonderful and charming person to have as a friend. One of his greatest admirers spent a winter learning to knit socks for him, but the spring arrived before the job was completed so she decided to present him with one sock and promise the other whenever it would be done. Arriving very early in the morning, Mr. Homan was found still in bed, but with the door open to the sunshine, and his pipe in mouth. He accepted the sock, and also the excuse with much affability. “When I get a wooden leg” he said, “the sock would be very handy, and ’till then I’ll use it for a purse!

Probably the custom of tying ropes round the small bathers arose after a very tragic occurrence which had happened to a young girl some years previously (1877). The daughter of Mr. William Exham was drowned one fine summer day in sight of his home at Courtnafarraga. She was, I believe, a charmingly pretty girl just back from school. She, her brother, and young Mr. O’Sullivan went out in a row-boat to shoot sea gulls. How it happened is hard to explain, but the boat overturned and the three young people were thrown into the sea. They all could swim and the sea was calm so Mr. Exham pushed an oar towards his sister and then swam ashore. The others did not follow. Mr. O’Sullivan’s body was never found and Miss Exham, on search being made, was discovered partly supported on the oar and quite dead. Can it be wondered that after this tragedy, parents discouraged their children from boating and bathing?

Musings by Bobby Chester on the Homans of Killiney strand in a letter to his sister describing events from the 1930’s

The text below is courtesy of Ronnie Haughton who originally transcribed the letter by Bobby Chester describing his memories of Killiney dating from the 1930’s.

All activities by the public on the beach were the sole preserve of the three Homan brothers Fred, Art, and Jimmy. There was another brother, Esmond who was sadly drowned in an overturned boat not far from the water’s edge.

I will now begin to write about some of the persons. I have mentioned the Homan’s I shall continue about that family. In 1916 the oldest member was referred to as Granny Homan, she was of German extraction but was not interned during the German war. During the summer season she operated a line of about 8 changing boxes or huts for hire, and swim suits for bathers. She lived in a whitewashed seaside cottage on the north side of the Bay. Her son Fred the youngest of the three, was by trade a carpenter, employed by the Board of works at Dunlaoghaire, he was also a fisherman and owned a few boats for hiring purposes. There was not a roadway connecting this cottage to the nearest road until Fred made one. He also constructed a series of about 6 chalets which he rented to holiday makers. He later bought a motor boat licensed to carry 32 passengers and crewed by his son, Fred and myself. We made 3 return trips each day if there was a sufficient crowd on the beach to warrant it. These trips were ’round the island’ i.e. Dalkey Island.

I have referred to Fred and now about his son, also named Fred and his 2 sisters, fair-haired twins. I could not tell them apart, but my best friend, Billie Haughton must have been able to differentiate since he married one of them!

The second youngest son, Jim lived in a small cottage on Station Road and was a part-time boatman. His main occupation was not boating, and I really do not know what was his living.

Fishing in Killiney Bay and selling the catch

Art Homan lived in the village and was a full time fisherman; he also had boats for hire and one special fishing boat the “Jane” bearing a licence number which allowed him to fish for salmon. This boat did not have spurs and spoon oars, rather it had two dowels for 16 foot oars, very heavy in a rough sea. Salmon were caught in a Seine net at the mouth of the Shanganagh River where it entered the Bay. This type of fishing was only carried out at certain times of the year and at high tide. I always found it exciting, one could never tell what the net had caught until it was hauled in. Every “shot” of the net did not catch a salmon. As soon as one was caught it was “clouted” on the head with a big stone to stun it otherwise the salmon bruised itself by threshing about in the death throes. The same Seine net was used for catching mackerel. The use of the net for this purpose is an interesting experience. The shoal of mackerel move south to north each year arriving in the bay in early August. It is a lovely sight to see a shoal of mackerel at play. A large shoal of mackerel may contain a million fish. When they toss and leap, devouring millions of herring fry bursting through the surface of the water creating what seems to be rough water on an otherwise placid sea. I have seen a good catch in a good season, as many fish as would fill the fishing boat “Jane” up to the gunwale Newspaper article here This glut of fish often could not all be sold and so it was used as a field or garden manure.

There are 3 other modes of fishing which I would like to write about and tell typical story about each. Firstly Trammel fishing consists of constructing a long fence of netting about 8 or 10 feet high having corks attached to the top rope and lead weights to the bottom rope. Between these two ropes two nets are fixed one net is small mesh, like a mackerel net, a second is slung loosely between these ropes and has a mesh of about one foot. The whole length of the net may extend to a quarter of a mile. This net is shot in a straight line following the coast off shore on the “edge of the ground.” In Killiney Bay this is about 400 yards off low tide mark where the sandy bottom meets the rocks or gravel. Passing fish become entangled between these nets which are shot about an hour before a change of tide.

One story in my experience of this fishing occurs to me. All sorts of fish may be caught in these nets. There is a fish called the angle fish shaped something like a plaice except that its mouth extends around half its body so that it could engulf something as big as itself. Moreover this mouth encloses rows of dozens of very small sharp teeth. On this occasion which I mention Fred Homan and I were “long line” fishing. Fred was rowing and I was hauling the line over the stern of the boat and throwing each captured fish down on the floorboards. Fred was sitting amid ships, one foot (we were both bare footed) on the floorboards, the other, to give purchase to his rowing, was braced against the mid-ship bench. To give some rest to his braced leg, he changed feet over and dropped his tired foot to the floorboards, in this manner he deposited his foot into the mouth of the half alive angling fish. Afterwards he had to visit the doctor to have some of the teeth removed. The second means of fishing in the bay is by the “long line”. This is a very strong line up half a mile in length at intervals along its length “snoods” are attached. “Snood” is a short length of thinner line with a fish hook attached to its free end baited with lugworms. Lugworms are found by digging at suitable places in sandy black bottomed clay. There is quite an art needed for this activity, because the worm often 9 inches long and as thick as a finger can burrow as fast as a man can dig. The line is set and anchored in a known suitable site, and left to rest for a couple of hours like the trammel net but this net is “shot” in a zig zag fashion and anchored by stones at each zig zag.

All sorts of ground fish and near ground fish may be caught is this manner. Local fishermen display their fish for sale on a spread tarpaulin on the beach. One day I was rowing for a Dunlaoghaire fisherman and a “spent” cod over a yard long was caught These “spent” fish are so emaciated after the mating season as to present an appearance almost skeletal. The fisherman ordered me to land at a point distant from the crowds on the beach. He gathered some seaweed from nearby rocks and stuffed all of it down the fishes gullet, followed this by an empty Guinness bottle and rounded the thing off by the rest of the seaweed and sand. When washed and looking plump it was displayed among the catch. The third method of fishing is by the use of lobster pots in order to catch lobsters and crabs. These are constructed by attaching a housing of netting wire to a cylinder shape 3 ft long and 2ft diameter with a conical entrance at each end. They are baited by tying inside them a few pieces of discarded fish such as the heads of other fish.

About 10 to 13 of these weighted by stones are attached to a main rope about 20 yards apart, the free ends of the rope are attached to marker buoys. The fisherman usually has 5 or 6 of these “trains” of pots. They are “shot” in the afternoon in a selected spot, hauled up and re-baited the next day. Once in a while these strings of pots may be raided by someone other then the owner. A 25% yield is considered good. This is very exhausting work by both the oarsman and the fisherman. On the return journey the fisherman has a rest sitting in the stern of the boat while engaged in tying the claws of both lobsters and crabs so that they are unable to fight and damage each other. One way to make a crab retract its claws is to “spit” in its face. I often spent a Sunday forenoon preparing “dressed crab”. It is delicious in a summer salad of lettuce, lobster, crab, salmon boiled in milk. Young scallions, radishes and home-made mayonnaise and some home grown tomatoes. The catch of lobsters is held in a large storage pot until there is a sufficient number to warrant sending to market. Incidentally at the time I am writing about, 21 shillings was considered a good price for a baker’s dozen (13).

Homan’s of Killiney

Ken Homan on his memories of the family living and earning a living at The White Cottage.

This article first appeared in the Dun Laoghaire Borough Historical Society Journal No. 9 of 2000. Courtesy of Ken Homan/Anna Scudds.

In the latter part of the 1800s my grandfather was employed to maintain a seawater baths situated in a small cottage on Killiney beach belonging to Ayesha Castle (then called Victoria Castle). Enough seawater was hauled up by bucket to fill a boiler which heated the water, supplying one bath for men and one for women.

By 1920, my grandfather, Richard, had extended the cottage for his family.

In 1923, the family applied for a licence to run dances, and a family photograph shows a large, rectangular platform on the beach, which was the dance floor, with Chinese lanterns hung around on poles providing light. The following year work started on an indoor dance hall and tea rooms, which still exists today, standing out over the beach on pillars. The hall was licensed to take 125 people and the popular tea dances of the time were held on Saturdays and Sundays, starting at 8.00pm and finishing at midnight. When the last reveller had left, the hall was swept and cleared and the windows cleaned for the following day. De Vesci Lawn Tennis Club ran dances there for several years.

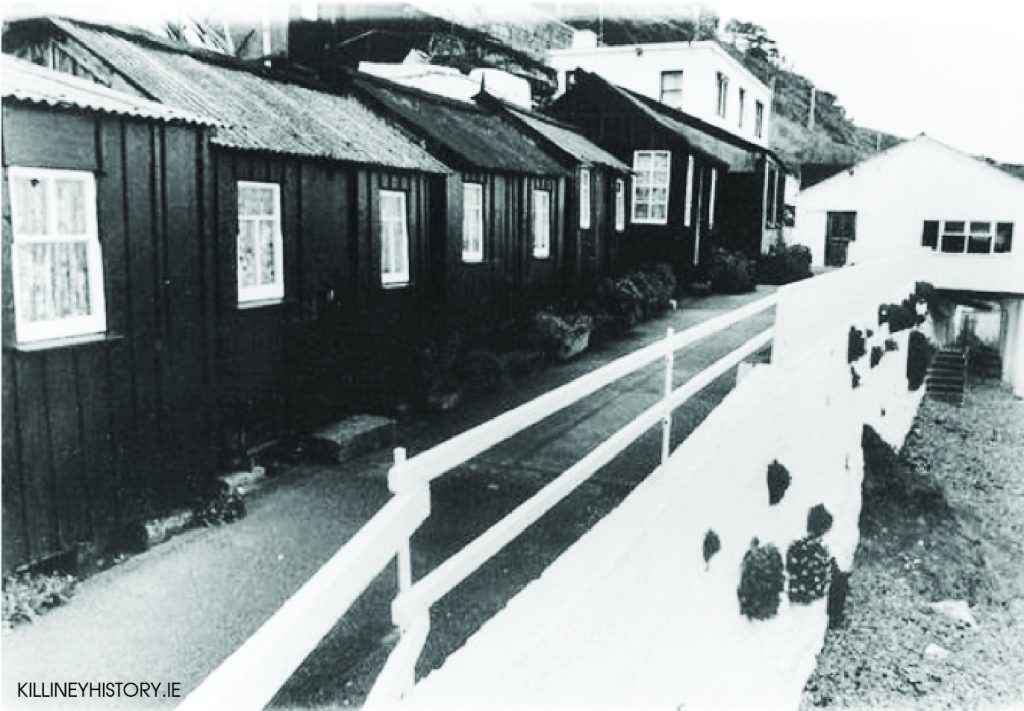

Swimming in the sea was very popular and Killiney beach had a number of beach huts positioned above the high water mark for swimmers to change in. Both sexes weren’t allowed to swim at the same time, with men restricted to early morning bathing. Seven single-roomed chalets were built to the side of the cottage in the early 1920s which were rented out to holidaymakers, including a number from England, and many would return each year. There was a penny meter for the gas and a jug of hot water would be left outside their door in the morning at the time requested. A long building above the chalets served as a self-catering kitchen, where guests would cook their meals on several cookers.

It was an inexpensive holiday with a breathtaking view to greet you every morning and the sound of the sea to lull you to sleep at night. The chalets continued to be let out until the mid-1950s, when people’s holiday patterns changed; the dances also ceased. Tea and sandwiches continued to be served at the weekends during the summer season until the mid-1980s, and many a hardy swimmer warmed themselves with a cup of tea after his or her dip.

During the winter months my father and brother (both called Fred) built clinker type boats -one a year-in the tea rooms, to be rented out in the summer to tourists and fishermen. Lobsters and crabs were caught between May and September in a line of eight pots – known as a train of pots – from Killiney to Bray, and herrings in the winter . Mackerel were much more plentiful then, and bigger, and we often caught large ray, which you hardly see now.

At the moment, seven boats are stored in the old dance hall. Years ago they would have been left on the beach with no fear of vandalism.

The Mullen family

Killiney Strand A Family Connection by Anna Scudds

This article first appeared in the Dun Laoghaire Borough Historical Society Journal No.16 of 2007. Courtesy of Anna Scudds.

Everyone has fond memories of their childhood spent at the seaside. I spent all of my summers at the beach, Sandycove, Killiney and Brittas Bay

The seaside was a different place in the 1920s, it was fashionable to visit for a day out. Sea bathing was considered a health-giving experience, and many people would visit a seaside resort and take a picnic. There were no annual holidays; they did not become formalised until the 1930s, so people took themselves to the seaside normally on a Sunday.

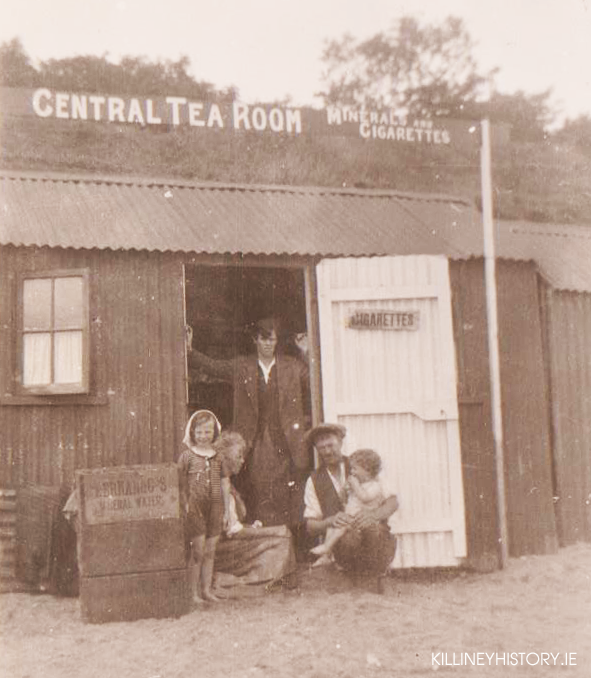

William Mullen and his wife Sophie were my great-grandparents, they lived at 1 Hill Cottages in Killiney village. During the First World War, William went to Liverpool and worked in a munitions factory. When he came back to Killiney after the war, he set up an enterprise on the beach.

There was a small marquee, rowing boats and a larger boat with a motor called The Hyacinth. This would be set up at the beginning of the summer and one of the family would stay on the beach in a small chalet/hut to look after it all.

They sold cigarettes, minerals and tea; boiled water was also sold. People would come to the beach with some food and bring tea, and boiling water was provided for them by vendors on the beach like my great-grandfather, Stanleys and Homans.

The Hyacinth would take trips around Killiney bay and at night it would be moored in Dun Laoghaire harbour. Every night it would make its way through Dalkey Sound and on to Dun Laoghaire, many times my mother would take the boat trip around to its moorings.

I am not sure where it was moored in the harbour as no records exist for that period. Mooring licences were introduced only around the early 1960s. Locals from the area used to look after patches in the harbour, where they laid moorings that were then hired out. Some of the names from that time were McDonald and Blackmore.

My great-grandparents had seven children, six sons and one daughter. At some time they were all involved in the enterprise. I know that their daughter, Kathleen, was part of it because there is a photograph of her at the door of the chalet/hut. My grandfather John was not so involved; he was living in Birkenhead when it was set up and when he came home to live in Ireland it was up and running.

We still love going to Killiney, summer or winter; each season weaves its own magic. It holds great memories for me, both in the past, in my childhood, and those of my children. We now have another generation to take to the beach, a new grand-daughter, although small and born only in June 2006; she will be the sixth generation in our family to have associations with Killiney strand.

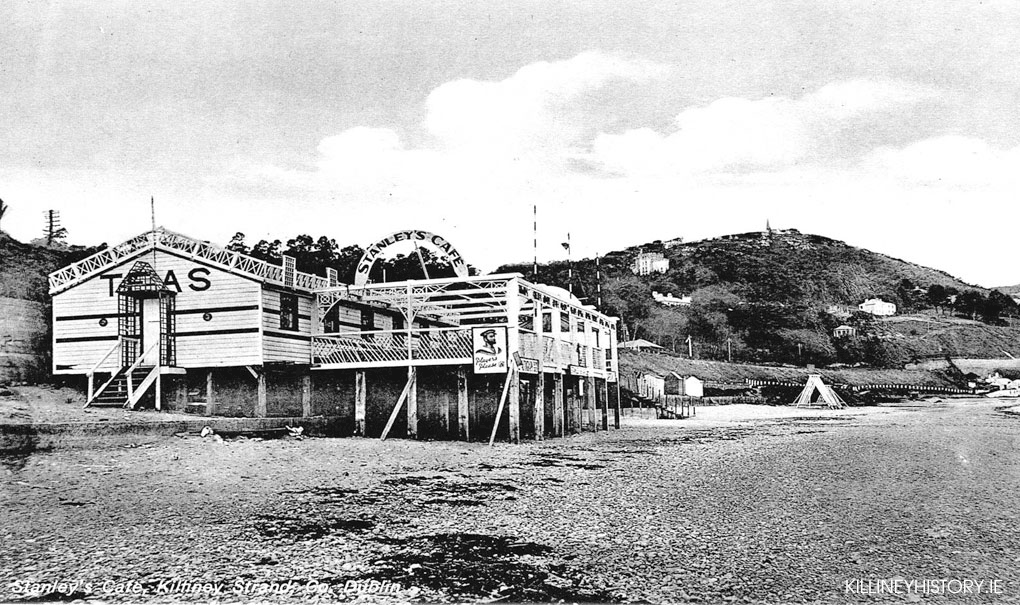

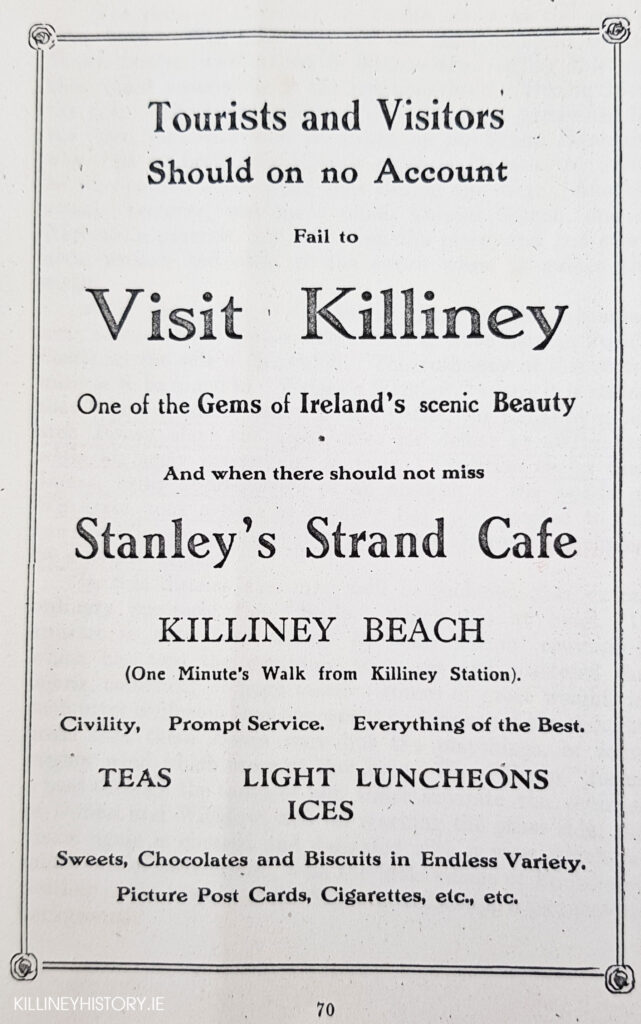

Stanley’s Strand Cafe

Stanley’s Strand cafe was run by the Stanley family who also ran a grocers shop in Ballybrack, Thomas Stanley & Co., grocers, tea, wine and spirit merchants. They also published a number of postcards of the area, one of which shows their fine establishment on the beach which incorporated a large open terrace area taking advantage of the views over Killiney Bay.

The far end of the strand, below Military Road

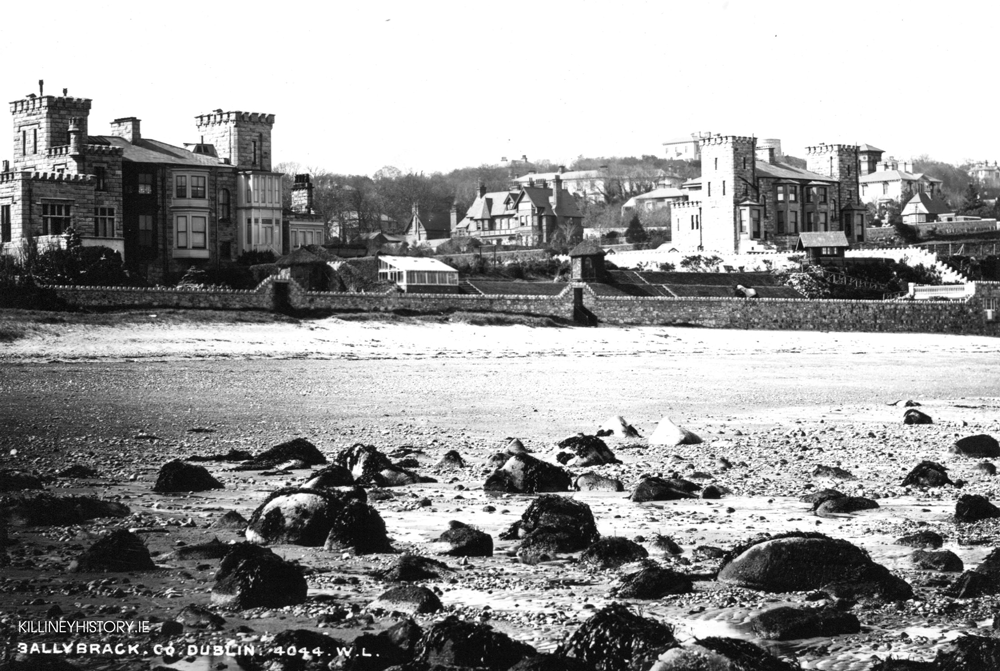

The semi-detached castles

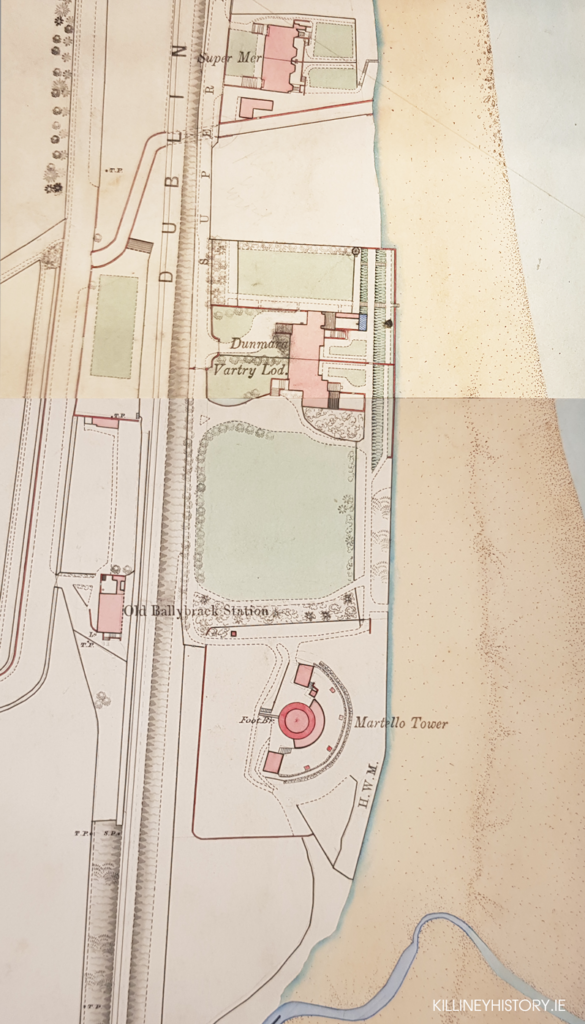

A remarkable pair of semi-detached, stone-built houses are a conspicuous feature of Killiney beach. These houses, which include Vartry Lodge, Dunmara, Carraig-na-Mara and Supermare, are the work of architect George Wilkinson who designed many railway stations and workhouses. They are constructed in rustic granite block-work with battlemented towers and wings. With their stonework towers they are successful in creating a defensive appearance although inside they are typically Victorian in their comfort and decoration. These houses, and the Martello tower which has been converted to residential use, directly overlook the sand and shingle of the beach, at the point where the Loughlinstown river joins the sea.

Wilkinson also designed Temple Hill for the Hone family, an impressive Victorian house with a fine temple in its grounds, currently owned by the singer Bono.

Attribution for the above currently unknown.

Vartry Lodge and the arrival of mains water in Killiney

One of the pair of semi-detached castles (previously called Strand House) was renamed Varty Lodge in recognition of it’s owner, Sir John Gray, who was responsible for bringing mains water to Dublin City from the Vartry reservoir in County Wicklow in c.1863. He was chairman of the Dublin Water Commission and was instrumental in the purchase of lands around Vartry for their use as a reservoir to serve the city of Dublin. He was also the proprietor of The Freeman’s Journal.

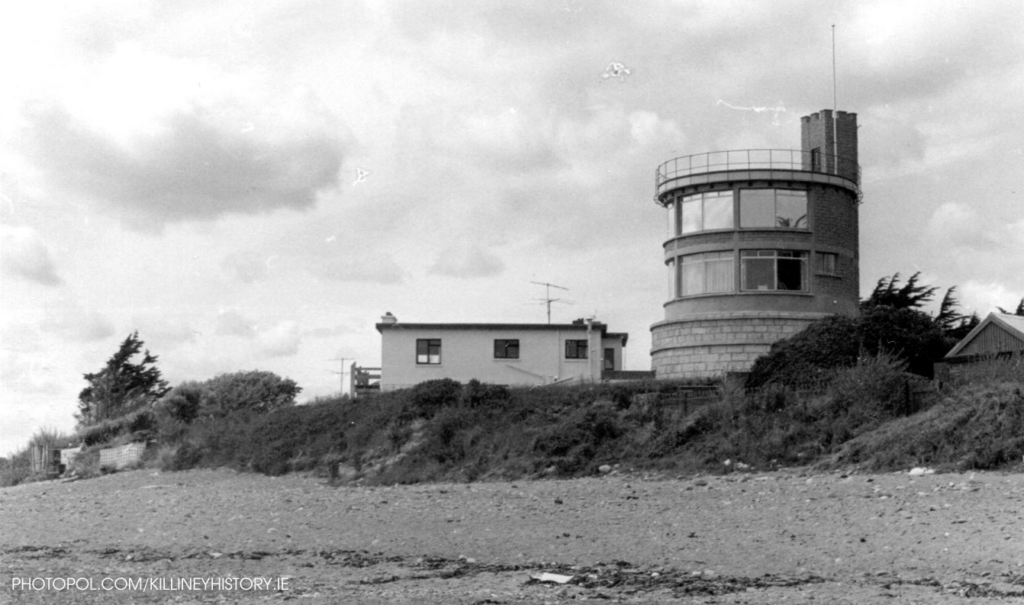

Martello Tower Number 6

Sighting of Waterspout in Killiney Bay c. 1838

From Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy Series I, Volume I 1836/40 pp. 358-359

Rev. Dr. Dickinson gave a verbal account of a remarkable waterspout, which he had observed at Killiney during the last summer.

Towards the end of the month of July, about 10 A. M., while standing on the shore of the bay of Killiney, his attention was directed by a friend to a waterspout, distant about a quarter of a mile from the land. It was not similar in form to the representations of waterspouts usually given, and may therefore deserve to be noticed. It was shaped like a double syphon, the whole being suspended at a considerable elevation in the air; the longer end of the syphon reached towards the sea, and appeared to approach it nearer and nearer, till, at length, its waters were distinctly seen rushing into the deep. The loop gradually lowered, as if sinking and lengthening by its own weight, while the up- per part of the syphon seemed not to lose in elevation. At length the loop burst, and there were three streams of water pouring into the sea, two of those streams still continuing united by the arch at the top. The breadth of these streams gradually diminished till they became invisible, but their length seemed undiminished as long as they were at all seen. The quantity of water poured down must have been very considerable, as the bubbling of the sea beneath could be distinctly observed.

Dr. Dickinson was informed that a waterspout fell a few days after inland, towards the Three-Rock mountain. It is said to have done some injury; but his informant did not see it, and he could not, therefore, ascertain its shape.

Tragic plane crash off Killiney Strand in 1955

The piece below was brought to our attention by Anthony Deegan. It is an extract from ‘Sit Down, Guard!’ by Eamonn Gunn.

It was August and we were having one of those rare, fine summers. The weather had been very warm for weeks, and crowds were flocking to the beaches. As quickly as possible we made the journey through the dense holiday traffic to Killiney, where the beach was packed with day-trippers. On arrival, I was at once aware of the crowd of onlookers near the water’s edge. They were agog at the sight of an elderly, very distressed woman attempting to wade seawards in the shallow waters to reach a small aeroplane which was half submerged some hundred yards off shore.

The small biplane had apparently got into difficulties while flying over Killiney Bay and had crash-landed into the sea, killing both occupants. I discovered that one of the victims was this poor woman’s only son. She presented a most pitiful sight: up to her waist in water and overwhelmed with grief, while the distressing scene was sullied by the presence of a swarm of onlookers. I was incensed at the distasteful spectacle of the gaping crowd insensitively staring at this broken- hearted mother whose distress, so clearly obvious to all, was being turned into a gigantic open-air peepshow.

Feeling deeply for the unfortunate woman, I appealed to the faceless crowd to show some compassion and disperse. I firmly escorted her out of the water and back to the waiting police car so that she might be spared the trauma of seeing her son’s body being taken from the sea. Sometimes you were torn between the importance of doing your duty and a dread of being unkind or officious!

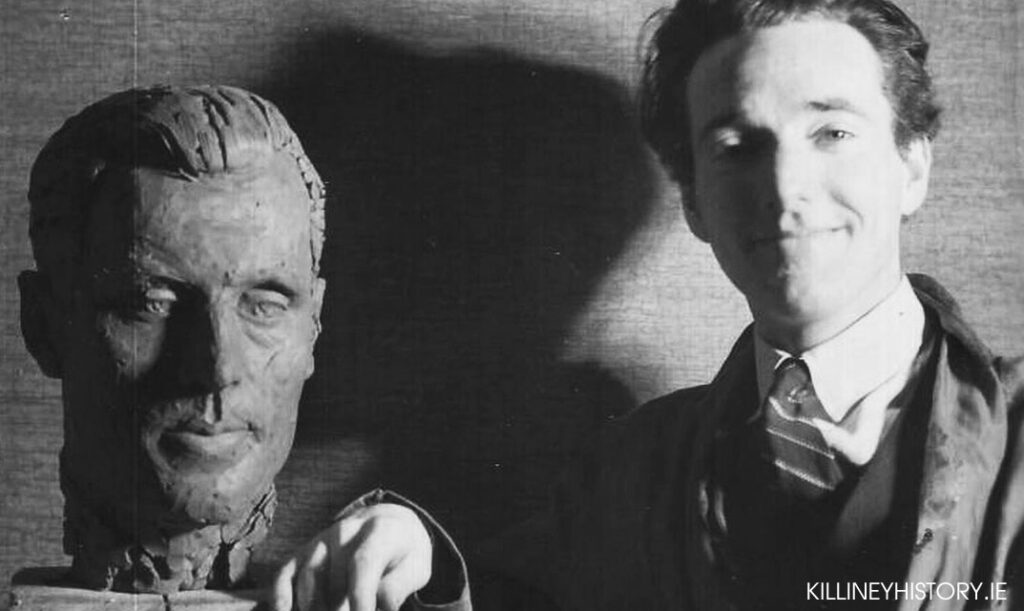

Further investigation suggests the victim was Frank Beatty, a barrister, called to the bar in 1947 and working on the Meath and Westmeath circuits in the early 1950s. He had been learning to fly in a two-seater plane. The plane lost power off the coast at Killiney and plunged into the sea, killing Beatty and injuring the pilot, a friend of his.

The photograph below was taken by Michael Hill and it shows the recovered aircraft on the beach beside Homan’s White Cottage. Michael was a young boy at the time the photo was taken using his mother’s box camera 620.

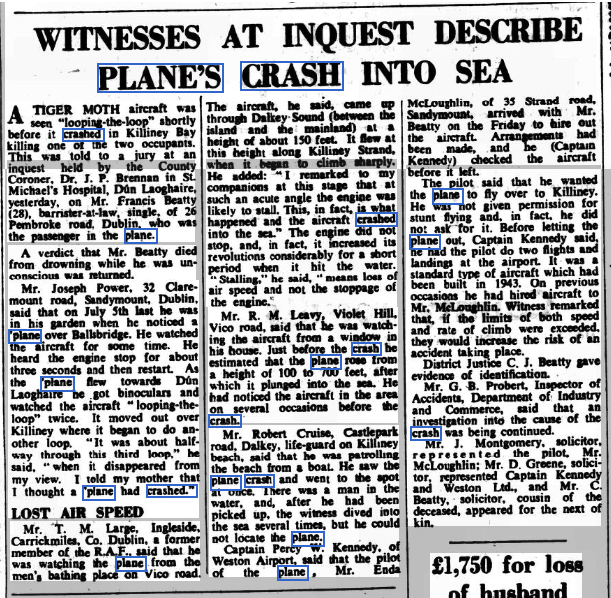

Barrister Killed in Plane Crash -Donegal Pilot Escapes (Derry Journal 18 July 1955)

While hundreds of people on the beach at Kiliney. Co. Dublin, watched a low-flying plane it crashed into the sea 200 yards from the shore, killing one man and injuring another.

The dead man is Mr. Francis Beatty (29). barrister-at-law. 26 Pembroke Road, Ballsbridge. Dublin, who was a passenger in the plane and the injured man is Mr. Enda MacLochlainn. 25 Strand Road, Sandymount, Dublin, who was the pilot.

Mr. MacLochlainn was thrown clear when the plane hit the water and he was rescued by people in pleasure boats who rowed towards the wreckage. which sank within a few minutes. He is a son of Mr. Sean D. MacLochlainn, Donegal County Manager, and Mrs. MacLochlainn.

The plane, a Tiger Moth from Weston Airport, Leixlip, crashed, according to eye-witnesses, while the pilot was attempting to climb.

The first to reach the scene was a boat rowed by two people on holiday from Liverpool. Mr. Ronald Windsor and Miss Brenda Kane. Miss Kane said: We were rowing along in the boat when a plane flew very low over us. It crashed into the water very close to where we were and there was an explosion as it hit the water. We rowed towards it and we saw a man in the water beside the tail of the plane. He had blood on his face and we tried to get him into the boat but he was too heavy. He kept saying: ‘There is a man in the front seat’. He appeared to be very dazed and he asked ‘How long have I been in the water?’ We told him that he had been in the water only a few minutes and we kept him afloat until another boat arrived.

Mr. MacLochlainn was taken to St. Michael’s Hospital Dun Laoghaire. where it was stated later that his injuries were not serious.

Many people on the beach expressed the opinion that the pilot had been in trouble and had intended to land on the beach, but when he saw how crowded it was, he turned out to sea. It was stated at Weston Airport that Mr. MacLochlainn was not a member of the Aero Club of Ireland. but that he had held an Irish pilot’s licence for the past few years and occasionally flew from Leixlip. It was believed that he had learned to fly while in England.

Mr. Beatty was the only son of District Justice Cyril Beatty and Mrs. Beatty.

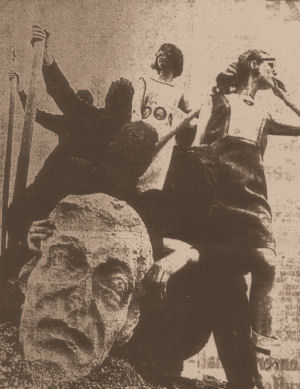

Nelson’s head on Killiney Beach 1966 by Pól Ó’Duibhir

One day in late March, 1966, I was walking along the station road in Killiney when my eye was caught by something unusual happening near the waterline in front of Homan’s. One of Homan’s long rowing boats was partly drawn up on the beach and seemed to be flanked by balaclavad figures presenting oars. It was too far away to be sure of what was going on. I had my camera across my shoulder and I set out for Homan’s. When I got there the action, whatever it had been, was clearly over and there were just a few ordinary looking people hanging around.

I was convinced, however, that something had been going on so I started photographing what remained. The boat was still there but there were no balaclavas and no oars. There was an odd looking sack which clearly contained something very heavy. I thought of a body but figured it wouldn’t fit. It was heavy enough, though, to leave a deep trail in the sand. The guys eventually got it as far as their car, an Austin Mini parked on the outcrop which can be accessed from the road. I couldn’t see the registration number and went round the front of the car for a better view. Quick as a flash, one of the people was sitting on the ground obscuring the registration plate. At this stage, I figured it might not be in my interest to hang around much longer and I scarpered.

I thought no more about it, writing it off as one of the mysteries of life. Then, unexpectedly, the plot was revealed. The Evening Press, of 2 April 1966, carried a photo, on page 4, which explained everything. The people I had seen on the beach had got a hold of Nelson’s head, which was indeed missing at that time. They had taken a photo at the waterline with the head in the foreground. I don’t know whether the photo had been commissioned or whether they subsequently managed to flog it to an agency. But, two young ladies had been photographically patched into the background in the photo studio, and the result ended up as a fashion shot in the Evening Press.

I had been kicking myself for the last 40 years that I had not kept a copy at the time. And, of course, I had forgotten subsequently the date and never worked up the application to track it down. However, I was recently in the research section of the Public Library in Pearse Street, in Dublin City, and learned that they had newspaper archives going way back. So, one recent day, I requested copies of the Evening Press, starting with March 1966 (the month Nelson was blown up) and resolved to look through every paper until I found it. Imagine my surprise when it turned up as soon as April of that year. The reproduction (below) is a scan of a very poor quality newspaper reproduction, but it does make the point.

I contacted the Irish Press photo archive in the hope that I might be able to lay my hands on a good quality photo print (or maybe even a few of them – they seldom come in ones). They tell me it cannot be traced, so you’ll have to make do with the current reproduction.

We reproduce the above courtesy of Pól Ó’Duibhir who originally posted this article on his website photopol.com

Newsreel of Killiney Beach in 1937

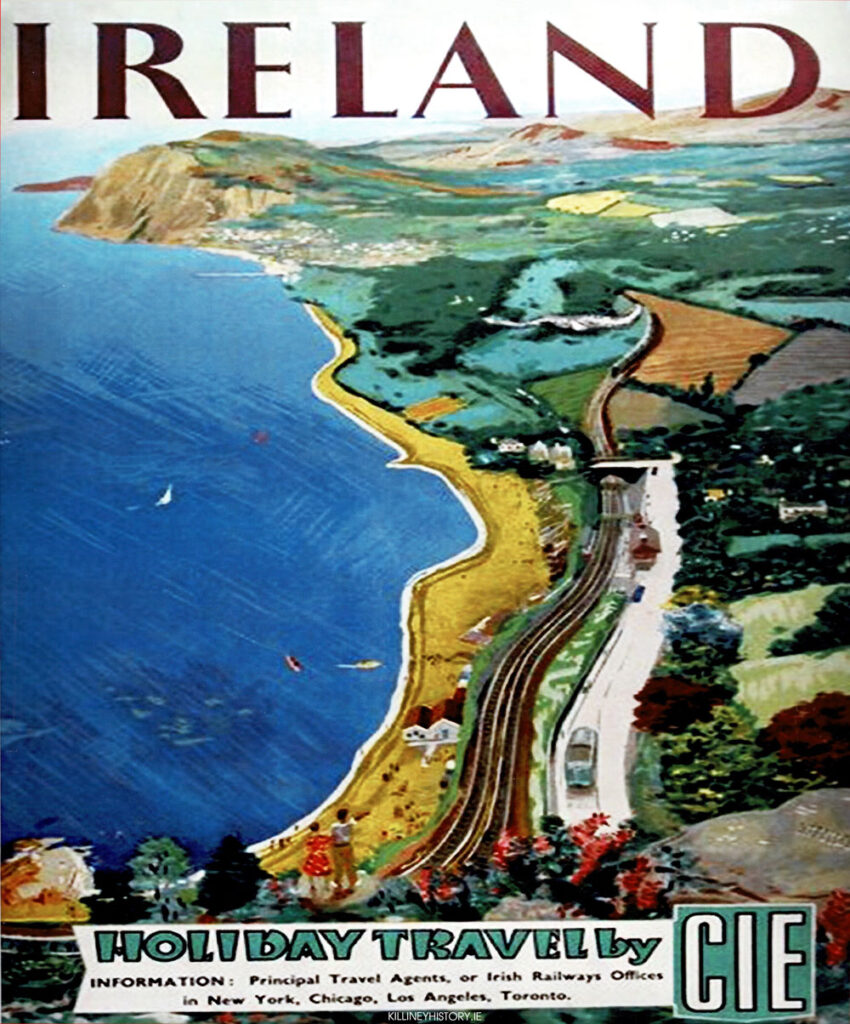

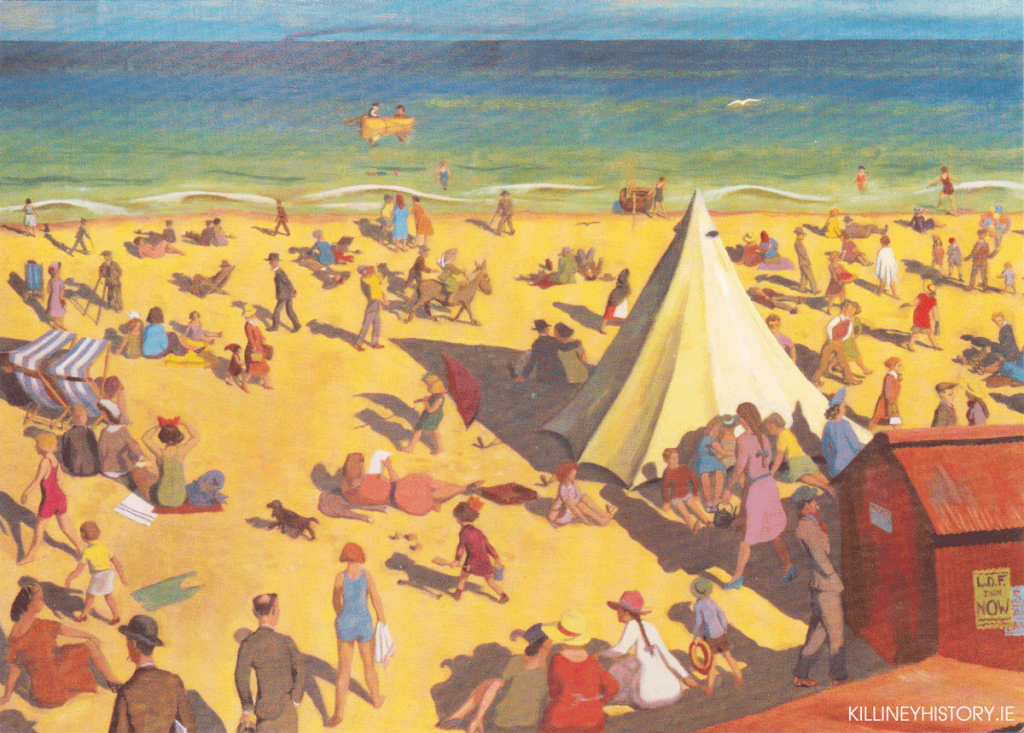

CIE Poster c.1930