Introduction

I wasn’t born in Ballybrack. I came there with my family in 1954. The story up to then was that I was born on the Southside within the canals, but lived in Howth village until I was about 5. My mother ran a shop there, the Gem, which sold newspapers and sweets and so on. We came to Ballybrack because, after an interval of about five years without one, my mother wanted once again to spend her time running a shop and Ballyrack just turned up on the map.

The Shop

The Ballybrack shop was then known as CNC, the origins of which name nobody seemed to know. There was speculation that it might have meant Cigarettes, Newspapers, and Confectionery. Confectionery referred to sweets and we did sell them and the other two items. Another explanation offered was Cash No Credit, but that didn’t fit the bill at all (so to speak), because we not only sold newspapers, we delivered them and that meant we needed to give a week’s credit (tick), or run a “slate” as it was then called.

The slate brought its own problems. Some people were slow paying and some local children would come in trying to by sweets “on the slate”. This posed a serious problem for the shopkeeper who didn’t know if the kids were allowed sweets in the first place, and if they were, had they permission to put them on the slate. The poor shopkeeper, the Ma, had to play this one by ear. A number of people in the “big houses” had egos to match the size of the house and could be very tricky to deal with. Working class people always paid their bills, and on time.

There was also a Christmas Club, where people could pay in, saving up for Christmas presents, usually toys for the children. These were then ordered heading for Christmas from Walker’s wholesale in Liffey Street in town. There was also a small library, Argosy, where people could borrow books for a nominal amount. The Argosy people would come around regularly to replace the books, so it wasn’t a bad system. The shop also had a telephone which customers could use at whatever the local charge was at the time. There were occasional calls further afield, in which case you had to ring up the exchange immediately afterwards to get the charge.

An innovation which the folks brought to the block of shops was the Christmas lights. I had never seen anything like it. A thick electric cable spanned the block and bulb holders were just screwed into it at regular intervals, piercing the rubber and connecting with the wires inside. Bulbs, normal house bulb size but coloured, fitted in to the holders, and Bob’s your uncle. The setup was left there during the year and the lights were just switched on every Christmastide.

Estates

When we arrived, the only “estate” in Ballybrack was Daleview, down the side of the block of shops of which CNC was one. That was what I’d call old Daleview. The newer houses with a proper road exit onto the Wyatville Road came later.

What I’m calling “big houses” in the area, of which there were a good few, were for the most part simply detached houses usually with fairly extensive gardens.

When we came to Ballybrack the houses in Daleview were not connected to the main sewerage system. They had outdoor toilets at the bottom of the garden and every so often the Council’s “honeycart” (a big tanker lorry) would come around to empty the accumulated sewage from their tanks. The original honeycart was found in the grounds of Martello Tower No.7 in the middle of the twentieth century and is now in the Howth Transport Museum. It is unusual as it is a two-horse cart, needed because of the hilly terrain.

Other Shops

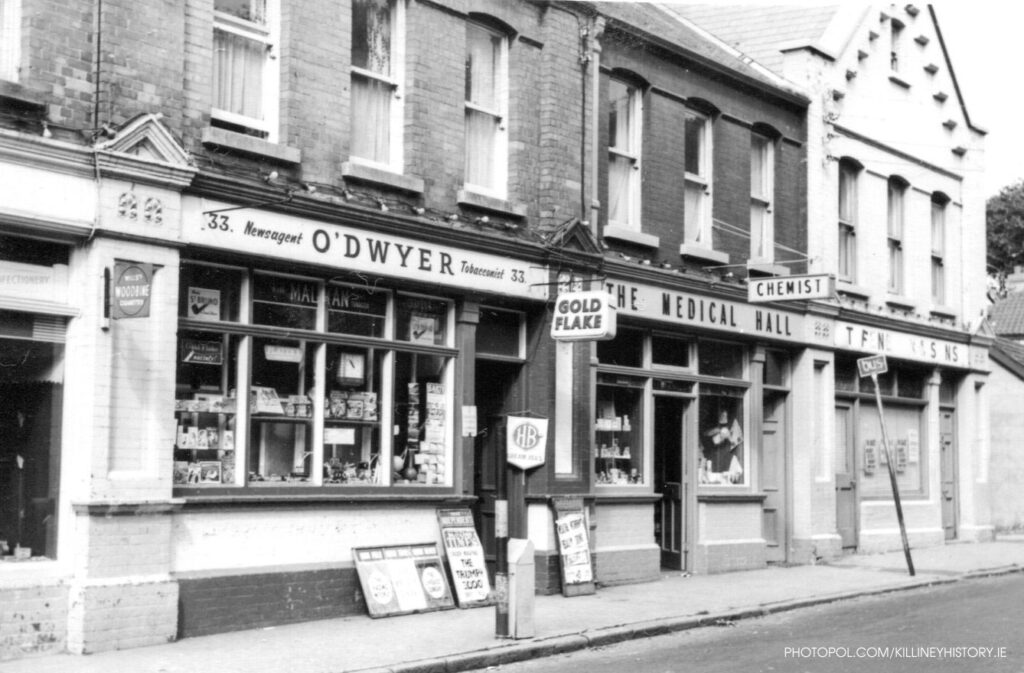

I’m trying to remember the shops that were there when we came. In our block was JB Murphy, at the corner of Daleview. He had the post office and sold the odd newspaper and some groceries, to the best of my recollection. When he died his son Dom took it over but he died young and it was then run by his widow. Next was our shop, and beyond us the Medical Hall run by Ger Kirwan. The shop on the other corner was run by Fenelons’s butchers at some stage, not sure if that was the case when we arrived.

The three shops, other than Murphy’s were lockup shops, that is the proprietors did not live over them. Miss Ryan lived over our shop. She was the shop’s landlady and was related to the priest who later became Archbishop of Dublin, Dermot Ryan. We lived over the Medical Hall, and Andy Reynolds & family lived over the fourth shop. His son Brian was a pal of mine growing up.

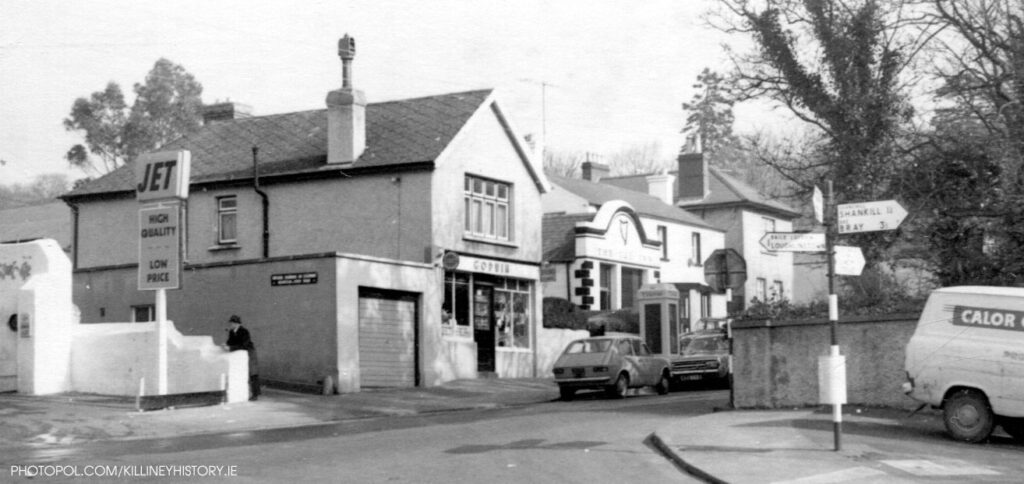

Heading down the village, there was Fenelon’s the butchers, though I suspect they came to that site after we had arrived. Next was Tom Stanley’s hardware store. He also had a big wooden tea rooms on the beach just at the way down by the railway station. Then, at some stage of the game there was Mrs Keane’s Post Office. And then the Ramblers Rest, one of the two “Bona Fide” pubs in the village. Gray’s garage was on the corner, and then, on the Military Road, Godwin’s just after the lane up to Mountainview.

Next the Igo Inn, the other pub in the village, also Bona Fide. Then Edward’s/Hallinan’s for groceries and at a later stage wine, where I eventually bought my first bottle for 7/6d. I think that was also where I purchased the weekly half dozen snipes (Guinness) for the Granny when she was living with us.

The Munster and Leinster (later Allied Irish) bank came much later. Mr Whitton was the manager and it was with him that I opened my first bank account in the late 1960s when I started working.

So, compared with how it looks today, the village was not a busy place, at least as far as shops were concerned. I remember that Fenelon’s used to slaughter their pigs up the back of their premises down the village and the day one escaped became a major event in village life.

As far as the premises next door to us were concerned, that was where Fenelon’s made the sausages. Willy, one of the men working for them, brought me in one day to see how the sausages were made. It was pretty disgusting and put me off sausages for a while. There was this big machine, like a huge mincer, into which all sort of meat was thrown followed by some buckets of blood. Then at one end, where the stuff came out, there was a tube which had a hugely long animal gut threaded onto its outside. Think of a frenchie but a lot longer. The gut was tied at the loose end and held back on the tube. Then the sausage meat came out under pressure and the gut was slowly released, making the longest sausage you ever saw. Finally the long sausage was twisted and cut into how you see them in the shop. This was truly artisan stuff.

Newspapers

Newspapers weren’t quite a loss leader, but the profit margin was very thin. They did, however, have the virtue of attracting people into the shop where they would hopefully spend more on other things.

The thing I particularly remember about the newspapers were the “Sundays” and in particular those arriving early Sunday morning off the mailboat. There was a lot of work to be done before the first wave of people arrived after the eight o’clock mass. Papers were counted and set up in a row on top of the counter. Many people used to buy one Irish and one English Sunday paper.

The English papers were, however, problematic from time to time. Occasionally one of them would not arrive at all, having been stopped by the customs in Dún Laoghaire for either obscenity or ads for contraceptives or articles involving contraception or abortion.

Today we scarcely remember the repressive atmosphere of the fifties and sixties. Books were being banned by the dozen. Through the intervention of my local TD, David Andrews, I actually got the Minister for Justice, Brian Lenihan, to have a certificate issued allowing me to import four books then on the banned list. But that’s another story.

I particularly remember a recurring front page headline in the Irish Sundays – customs posts blown up along the Border. This was the 1950s IRA campaign which fizzled out, to be replaced in the 1970s with its much more virulent successor.

Content apart, the newspapers, mainly the “Sundays” then posed another problem. They started bring out supplements, some in newspaper format others as effectively separate magazines. That created an enormous amount of extra work on a Sunday morning as all of these had to be manually inserted into the papers before they were laid out for sale.

At some stage along the way, newspaper printing methods changed. Previously the ink on the papers was dry and didn’t stain your hands. But then, with some new (offset?) printing method they came with tons of ink on. You could smell it and it came off on your hands, causing serious mortification when you went from handling newspapers to serving ice cream, leaving great big black pawprints on the cartons as you cut the ice cream into 1d, 2d, or 6d units, put on the wafers and handed the result to the customer.

I should probably mention here that Ballybrack had its own “newspaper” for a brief interlude during 1958/9, The Shanganagh Valley News. It had news, features, sport results, and paid advertisements. The format was Roneod (stencilled) foolscap, set up and printed in Broadstone and distributed widely in the area and abroad (written, edited, printed and distributed by one Pól Ó Duibhir). There was also a letterpress printers which produced stationery, visiting cards, memoriam cards, baptism certificate blanks, membership cards and Christmas cards. The business address for both of the above was 34 Church Road.

Shopkeeper Ethics

Before I leave the shop I should mention the Manual. There wasn’t a physical one, but the Ma had two golden rules for behind the counter. First “the customer is always right”. This is an important universal rule adhered to by any service provider who wishes to stay in business. Clearly the line would be drawn at obscenity or physical abuse, but otherwise, this is the shopkeeper’s creed. The second one applied more particularly to where we were, “keep your mouth shut”. This did not preclude casual conversation with customers but it firmly ruled out taking, or even appearing to take, sides in any local dispute. A sympathetic nod to one customer complaining about some injustice done to them would have the other party, usually a cousin of theirs, into the shop the next day complaining about shopkeeper bias. The villages of Ballybrack, Killiney, and Loughlinstown, were one genealogical area, tightly intermarried, and woe betide anyone coming between family members.

The Holy Acre

I have memories of the holy acre for a variety of reasons. This was the parcel of land bounded by Killiney Hill, Seafield and Military Roads which contained enough religious presence and prayers to save a whole village from eternal damnation.

First there was the Cenacle Convent. This was an order of nuns which originated in France and whose main activity was giving retreats. Myself and my pal, Brian Reynolds, from next door and a few others served as altar boys there. Other boys served in the local parish church. I served many masses there for a young curate on his first priestly assignment, a former pupil of my own school, Coláiste Mhuire. I learned later in life that he had subsequently been prosecuted for child abuse.

I take great pride in telling people that my mother “sold masses” in the Cenacle despite the fact that had she actually done so she would have been committing the sin of simony. Selling masses was a widespread practice but it was packaged as a voluntary contribution with an implied retail price maintenance ticket. In this particular case, participation in a Novena of masses in the Cenacle could be ‘purchased’ and a very elegant card was provided to give to the beneficiary.

Next there was the Archbishop’s Residence, Notre Dame, formerly and subsequently Ashurst. The archbishop in question was John Charles McQuaid, John Charles for short, who ruled the Dublin diocese with an iron fist and a network of spies from 1940 to 1972. The Palace was in Drumcondra but the Residence was in Ballybrack (technically Killiney). He is definitely another story.

Next the Holy Child Convent at the corner of Military and Seafield Roads. This was a posh girls school which attracted pupils from as far away as Dalkey, Maeve Binchey being a case in point. But one of Ballybrack’s own, Liz McManus (née O’Driscoll), is also a distinguished past pupil. Clearly I had very little to do with that convent.

Then, further down the Seafield Road, we had the Franciscan House of Studies, Dún Mhuire, which housed some highly intellectual fathers. One such, Fr Benignus Millet, scandalised me one day when he told me he read Agatha Christie for recreation. I was expecting to hear about some of the writings of the Doctors of the Church. It was Benignus who gave me my favourite Limerick:

There once was a lass from Cape Cod

Who believed in intervention by God

But ’twas not the Almighty

Who lifted her nightie

But Roger, the lodger, the sod

Planned Giving

While I’m on the subject of religion I have to mention the abortive Planned Giving experiment which the Archbishop attempted to introduce in Ballybrack on a pilot basis with the intention of extending it later across the rest of the diocese. The objective was to raise more money. There were churches to build and more priestly mouths to feed. Well, John Charles got in a crowd of American fundraisers who came up with a plan. Parishioners would pledge in advance to cough up a particular sum of money on a regular basis. Fine as far as it went. However there was an apparently clever range of incentives built into the scheme which almost led to its complete downfall.

The idea was to associate contributors with various pieces of church furniture. A whacking big commitment had your name associated with the high altar and so on down the scale to the cruets. If you didn’t merit an object your name would be inscribed in a golden book which would remain in full view in the sanctuary.

There was a justifiable and angry backlash at this scheme with the widow’s mite being quoted at the top of the list. The scheme became an enormous embarrassment to the diocese and all that was retained was the idea of pledging a regular contribution. The “auction” of the church’s family jewels was put off at least until another day.

If you’ll bear with me I have just one other religious item – the Preachers. I don’t know what church/sect they were associated with but they came out from town at weekends during the Summer and preached on Killiney Beach. The “sermons” were staid and almost polite. The main message was that Jesus needed you and you needed Jesus. Nobody paid a blind bit of notice of them unless it was to sort of listen in for a bit of entertainment. I distinctly remember one of their little leaflets:

Life is short

Death is sure

Sin the cause

And Christ the cure

Decimalisation

Shopkeepers and shop assistants become very adept at totting up money and change in pounds shillings and pence. I worked in Jersey for a summer where a man could tot up the day’s takings all in one go across the pound shilling and pence rows instead of doing the pennies first and then the shillings and then the pounds. Amazing.

Well, this skill was about to become redundant with the introduction of decimalisation in 1971. While the result was simpler sums, there was the transition to be taken into account. Advance bundles of the new coins were available from the Central Bank for training the shop staff, Clare Kane from Mountainview, Bridie Byrne from Daleview, and Rose Redmond from Church Road. Late night sessions when the shop was closed eventually did the trick and the transition was seamless on the day. When it came to the €uro, in the year 2002, I was long gone, as was the Ma, and even the shop itself. It, along with its neighbour the former Medical Hall, now houses the local Credit Union.

People

I clearly remember the Archbishop but never met him. My pal, Tom Ferris, was once offered a lift in the holy limmo on his way home from the bus at the Big Tree. I must check with him sometime how that conversation went. I occasionally walked up from the Big Tree with the Archbishop’s secretary, Fr. Martin, a brother of FX and an intelligent and very nice man.

I saw my first real corpse in Ballybrack soon after our arrival. Canon O’Rourke, the PP, had died and was laid out in the school for all the parishioners to come and pay their respects. Gave me the willies for many weeks afterwards.

Gregory Owens, of Stonehurst on the Killiney Hill Road, was an enthusiastic parishioner and frequently dominated the meetings of the religious Patrician Group, which were held in the Legion of Mary Hall at the Martello Tower. He was the Owens in Owens’s tea bags, an innovation on the Irish market at the time. I remember his son telling me that when delivering to Dunne’s, for example, they had to go in and stack the shelves themselves. This is a practice that subsequently spread to other suppliers – a sort of franchising you might say.

Gregory’s son Harry became auditor of the UCD L&H and I was a guest speaker there during his brief reign.

Parnell’s nephew, Harold de Mowbery Parnell, lived up the road in Maple Grove. I remember him as quite old, a sort of Chaplinesque figure. I saw him about but we never met. I gather he was a well-known meteorologist in his day.

Kylemore, further up the road just beyond St. Matthias church, was a private mental nursing home. I remember a man there trying to convince me that he was really Wild Bill Hickok. He did look the part but I had my doubts. Wild Bill was one of my comic cut heroes.

Alec Reid lived across the road. He was a friend of Sam Beckett and wrote a very good book about the playwright and author. He was a lecturer in literature in TCD and also did reviews for the Irish Times. His place was an open house and you’d never know who you’d meet if you chanced to be there.

Alec was a good friend of the journalist Peter Lennon, who made the film Rocky Road to Dublin which, after a brief showing in Earlsfort Terrace, was banned and only surfaced in more recent times. Through Alec, myself and Tom Ferris took part in the filming but fame eluded us when one of our student number withdrew her consent. On mature reflection on her part, she had come to fear that participation might adversely affect her future career prospects. That has been one of my big regrets. We should have told Peter to keep us in and just edit her out onto the cutting room floor.

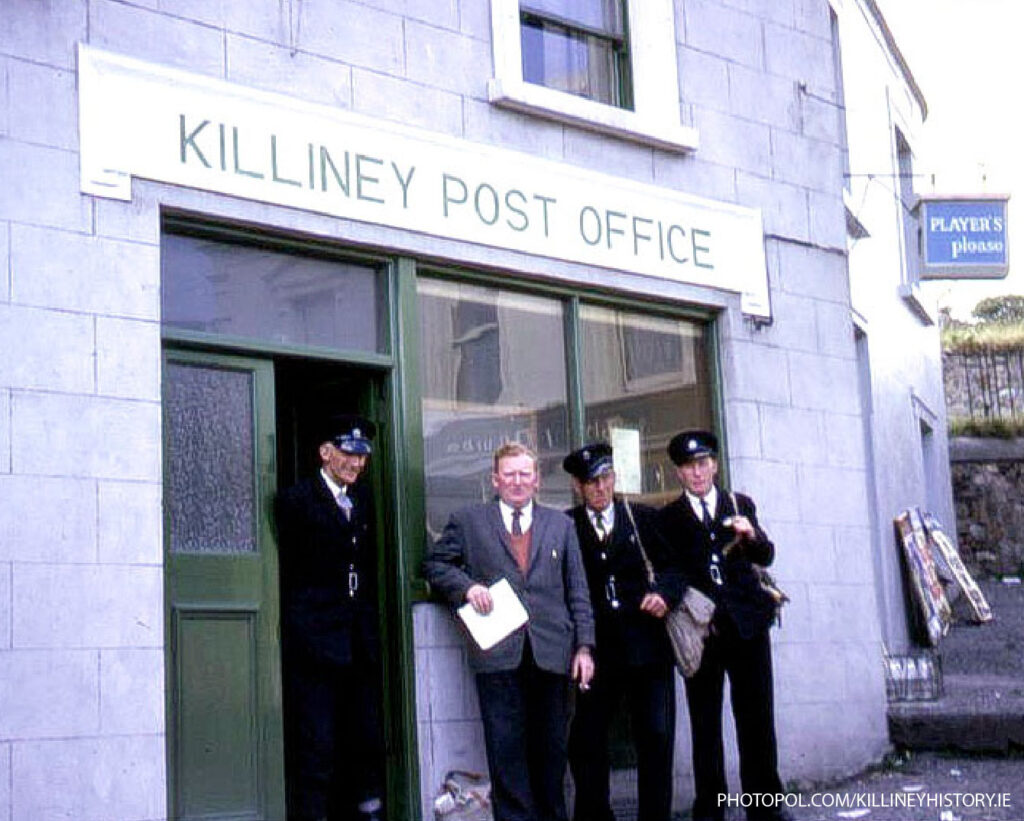

Michael “Holly” Cosgrave was one of the local postmen and I got to share his postal round in the run up to Christmas when the post office employed temporary staff to cope with the Christmas card deluge. His son, Gerry, is now clerk in the local RC church.

Mind you, between delivering post from the Killiney post office and doing a paper round from the shop you got to know a lot of people, and a lot more about them. A story that sticks in my mind concerns Brigadier Hudson who lived in Ballybrack House. His post, and his entry in Thom’s Street Directory, has him down as a Lieutenant Colonel, two ranks below Brigadier. But he might as well have been a General for all that mattered to us yokels. His wife ran a weekly charity shop at the house. The term “second hand” was in use then but I think it has now been replaced by some sort of euphemism like “not so new” or “pre-owned”.

Then there was Canon (Herbert Hamilton) Maughan, sort of detached from the Anglican church, who lived in “San Gregorio” Cherrywood and had his garage converted into a chapel where he celebrated “mass”. He drank in the Ramblers Rest with my father and other locals. He stood out in the street with his clerical garb – flashes of red or was it purple – and a wide brimmed round black hat.

Terence de Vere White, an editor with the Irish Times and a novelist, lived up the road just beyond Killiney Avenue. He wrote a novel about Edward Ball who put a hatchet in his mother’s head in Booterstown in 1936 and dumped her body in the sea at the bottom of Corbawn Lane in Shankill. I was born in the same house as Edward, 40 Upper Fitzwilliam St.

Noel Broderick, who was just a year or two older than me, kept pigeons in a loft at the end of his garden in Daleview. I could see it from the back window. The pigeons used to be taken away in trucks as far as England, Penzance I think, and then released to race home. They were ringed with an identifying ring which was taken off them when they arrived and put into a special clock which recorded the arrival time. It was Noel who bought our first book on the Facts of Life from the local chemist.

Desmond FitzGerald, the architect, lived in St. Declan’s, formerly and latterly Dorset Lodge. He designed the first Collinstown airport building which is still there today. He was a brother of Garrett FitzGerald, and father of Deasmhumhain (two Séimhiús) who was a friend of mine. I remember later being at Deasmhumhain’s wedding down the country. Garrett was there. He was Minister for Foreign Affairs at the time. Something was happening in the world that concerned him but his ministerial car had no radio and he was trying frantically to cadge a transistor off of any guest who might have had one..

Senator Hugh O’Donnell lived in Vartry Lodge the last of the castellated houses on Strand Road. We saw little or nothing of him. I think he had a disability or he was just very old. His wife did come into the shop though. In checking him out for this piece I find he was, in addition to being a politician, a businessman and playwright (recognized by his contemporaries as “being Ireland’s most banned playwright”). He corresponded with, among others, Yeats, Austin Clarke, Sean O’Casey, and Lennox Robinson. For some obscure reason his papers are in the library of the University of Delaware. My point here in filling in this background is that when we only come in contact with someone in the later period of their life, we have no idea what lies behind the bland exterior which presents itself. He was still alive, only just, when I left Ballybrack in 1975 (d.1976).

Vartry Lodge was so named by the widow of Sir John Gray who lived in that area. Gray was responsible for the Vartry scheme which brought water to Dublin city. The Ballybrack and Killiney Township/UDC took its supply from Gray’s pipeline as it passed through Rathmichael. However, as it was a gravity bleed it only reached so far up into Killiney and the local authority had to install a pumping station to bring the water to the people in the upper reaches of the village. The small railed woodland area beside the Killiney Hill obelisk is where the reservoir for this supplementary scheme was located.

I remember a man called, I think, McGill, who lived in the first of the castellated houses on Strand Road. He flew a Tiger Moth and one Saturday he crashed it into the Bay. That was the morning we set out for a week’s holiday in Butlins (Mosney). I loved going to Butlins but had very mixed feelings that morning as I would be missing the excitement on the beach for the rest of that day.

The first house on the left (they’re all on the left !) as you go down the Strand Road belonged to a man who was rumoured to have hanged himself there. That would have been in my time in Ballybrack.

One of the people the shop delivered papers to was Miss Barrington of Campanella. I mention her in particular because she represents an interesting connection with my own family history. She was a descendant of Sir John Barrington who had been Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1865 and 1879. He was, inter alia, the manufacturer of the lemon flavoured soap mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses. But more importantly he was the employer of my great-grandmother who was in domestic service to him in 202 Great Britain (now Parnell) St. That is the house she married out of in 1866. So that makes for a family connection spanning three generations.

History

This is not the place to go into the history of the area in depth, but a few teasers would not be out of place. Killiney Bay is full of history.

The settlement at the ancient church site on Marino Avenue goes back to the sixth century and may have been a purely female monastery. It gave its name to the area, Cill Iníon Léinín, church of the daughters of Léinín.

In the sixteenth century the area was a buffer zone between the citizens of Dublin and the native Irish O’Byrnes and O’Tooles who descended on them from the Dublin mountains in an attempt to reclaim the lands from which they had been expelled.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, before and after 1798, the British feared a sea-borne French invasion and initially set up a huge military camp in Loughlinstown as well as employing a French army officer in exile to advise on defending the Bay. Events on the periphery of the 1798 rebellion led the authorities to doubt the value of the camp which they closed in 1799. Permanent defences were erected some five years later in the form of the Martello Towers, some of which survive to this day. But that’s another story in itself.

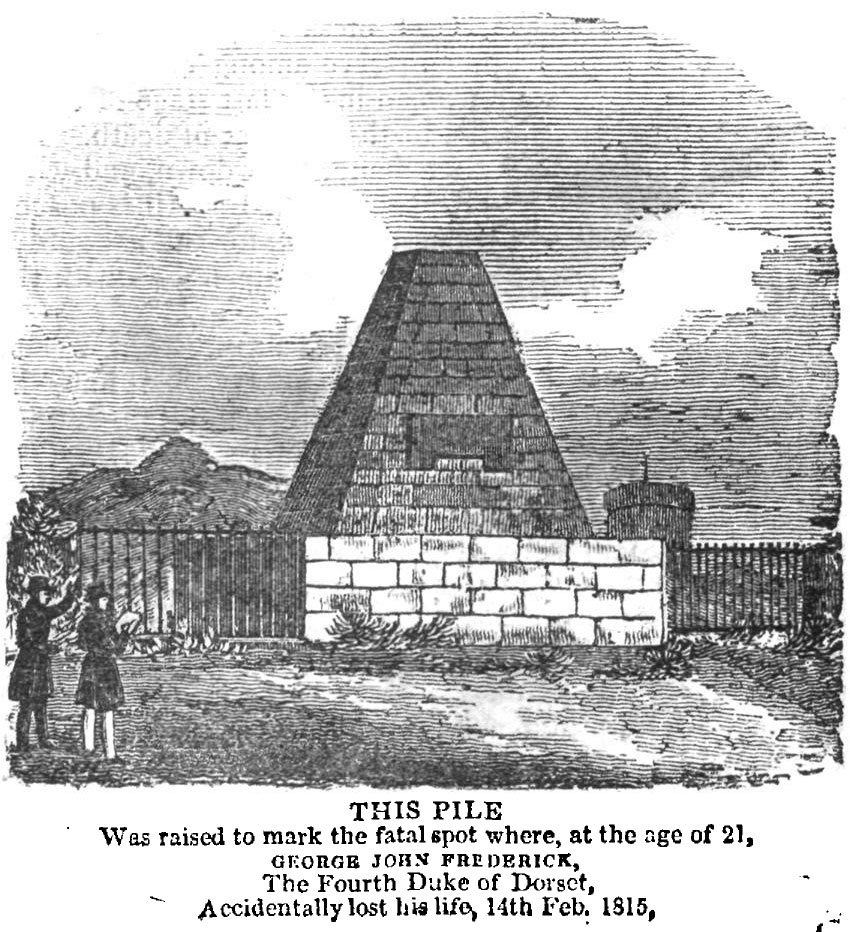

It’s important to remember that up to the beginning of the nineteenth century, the whole area was rural. The Earl of Meath’s hunt from Kilruddery covered ground as far north as Monkstown and Dalkey. We know Lord Powerscourt’s hunt went through Ballybrack because it was there that the Duke of Dorset died after a fall from his horse in 1815. A large monument to the Duke still stands just to the north of the RC church.

It was at the beginning of the nineteenth century that leases started being given to developers to build on the land and, with the coming of the railway in mid-century, the place boomed. So much so that when we arrived there were lots of detached houses in their own extensive gardens. Nevertheless you could look across at the camp ground in Loughlinstown and still see a vast expanse of greenery, particularly on the far side of the King’s Highway (N11). Today that is all filled in with housing and the vast, still expanding, Cherrywood business park.

Living Dangerously

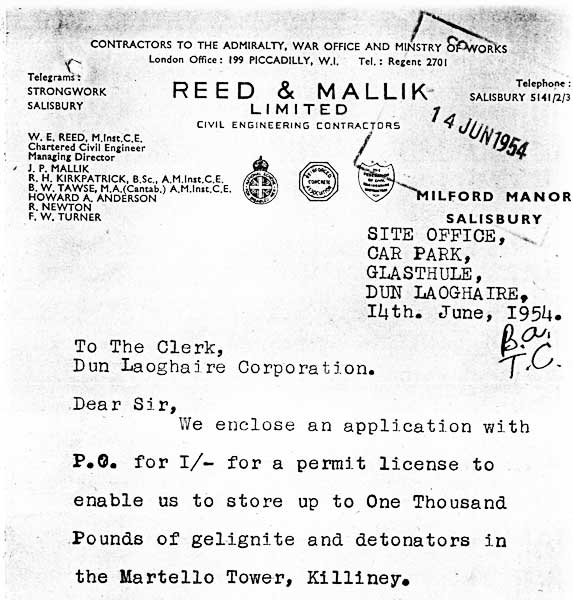

I’ll end with a little known fact from the 1950s. I mentioned the Martello Tower on Killiney Hill Road. The Legion of Mary had a hall beside the tower which was used for Legion meetings and local dances. I had attended Patrician meetings in the 1960s. But earlier in 1954 the tower itself was used to store a thousand pounds of gelignite and corresponding detonators. I don’t know if people meeting there would have been comfortable at that time had they known this. The application for a licence to store the explosives from the company concerned included a Postal Order for one shilling.

Read more about Martello Tower Number Seven here.

About Pól Ó Duibhir

Pól Ó Duibhir was born on Dublin’s Southside and spent half a century on the northside where he lives today. During a Southside interlude of some twenty years in Ballybrack, in Killiney Bay, he developed an interest in its local history which turned out to be varied, exciting, and at times important on a national scale. He has published and given a number of talks on this subject.

Here he remembers when he first came to Ballybrack in 1954.