Introduction

This post is dedicated to the memory of Niall O’Donoghue who painstakingly restored the tower to it’s former glory. Niall sadly passed away on the 8th of May 2022. The text below is reproduced from the information pamphlet which is available to visitors to the tower and was written by Niall. The other sections of this article including photographs and images have been contributed, with thanks, by Pól Ó’Duibhir, a friend of Niall’s. Thanks also to Pippa McIntosh for the recent photo of Niall in the tower.

Welcome

Martello Tower Number Seven was an enfilading fortification located on Tara Hill, Killiney Bay, some 252 feet above sea level and 400 yards inland from the sea. It is a truly unique Martello fortification being the only one that forms a combined Tower, artillery store, dry moat, and three-gun walled battery area surrounded by a steep glacis bank with a separate gunner’s cottage and gunpowder store alongside. It stands 10 metres tall and is constructed of Ashlar cut granite stone, with pitch pine flooring and joists. There was no well on the site so rain water was collected from the crown of the Tower and stored internally in a 490 gallon tank.

Background

The Martello design evolved from a round tower built by the Genoese at Cape Mortella Point in Corsica. It was attacked by a British naval force in 1794 but they found the Tower extremely robust, as cannon fire was unable to penetrate the thick rounded and battered walls. Mortella Point was so called because the Myrtle bush grew profusely there and the name led to the British use of the term Martello to describe this kind of tower.

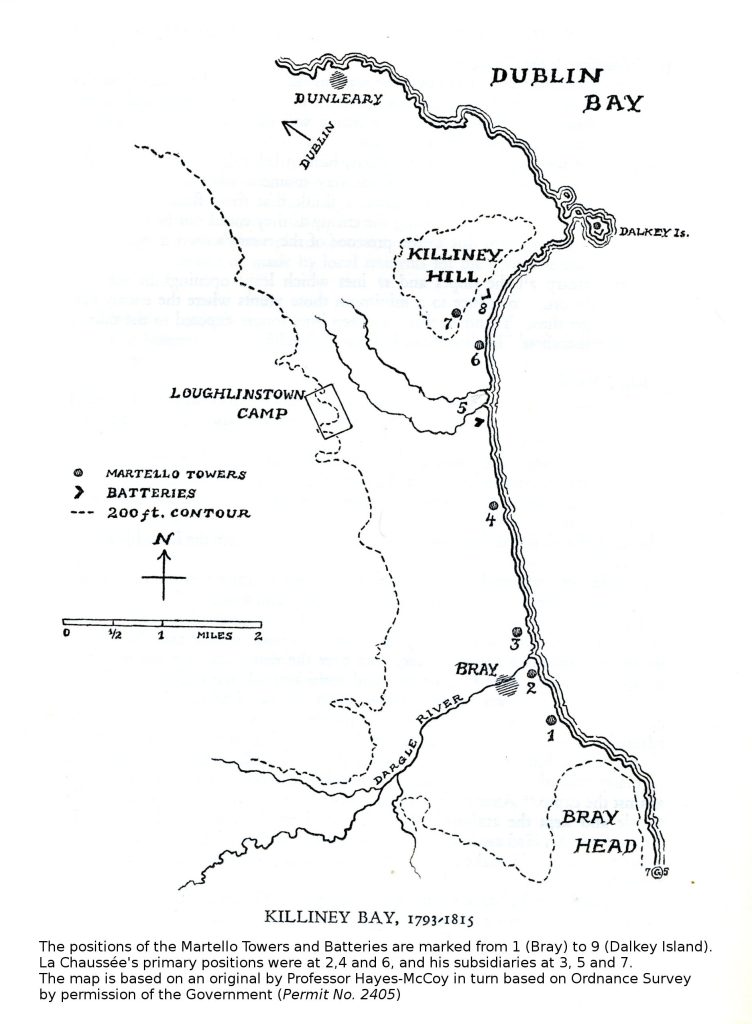

Lord Carhampton, Commander of the Crown Forces in Ireland, instructed Major le Comte de La Chaussée to prepare a coastal defence plan for Killiney bay. The Major presented his incisive plan, outlining the works required in the short term, in February 1797. The report was accompanied by a coloured map of the bay, supporting his analysis. La Chaussée, probably a fugitive from the French Revolution, had joined the British forces as a defence engineer and cartographer. His instructions were in English and the report itself was in elegant French. The report left open the possibility of the subsequent construction of more permanent defences against a French attack.

The French had already attempted to land forces in Ireland, and it was not long before the British authorities embarked on an ambitious programme of permanent defences. These consisted of fortifications, mounted with 18 and 24 pounder cannon, and they stretched from Bray to Balbriggan. The works which were commenced in 1804 were completed the following year, under the direction of Colonel Benjamin Fisher.

In the course of these works Major Fisher ordered the destruction of the famous ancient rocking stone in Dalkey near Bullock to procure a few pieces of granite for the Bartra Martello Tower. A report some years later stated that Colonel Fisher died by his own hand in a water closet.

Of the 16 fortifications south of Dublin, 14 had Martello Towers, eight of which were accompanied by batteries. There were also 2 batteries without towers: number 8, Limekiln Battery, at the junction of the Strathmore and Station Roads, Killiney, which was removed around 1846 in the course of the construction of the new railway line to Bray, and; number 5, on the Shanganagh cliffs, which was abandoned in 1812 due to coastal erosion. Both batteries had three cannon.

The Towers, with number 1 at Bray on the promenade, later demolished without trace. Number 2 is located near the harbour and had a three gun battery. Numbers 3 & 4, were also removed due to coastal erosion. Number 6, on Loughlinstown beach, has a circular two story house built on top. Number 7 has been restored. Number 9, with a gun battery, on Dalkey Island, is abandoned. Number 10 is now a dwelling. Number 11, Sandycove Tower, is now a Joycean Museum. Number 12 was taken down and was located in the Peoples park, Dunlaoghaire. Number 13 was removed during the construction of the Dublin to Kingstown railway. Number 14 is at Seapoint. Number 15 is at Williamstown and was a two cannon Tower; a one third lower portion of the Tower is beneath ground level which was raised by Dunlaoghaire Corporation; the sea used to surround the base of this Tower. Number 16, at Sandymount, was also a two cannon tower. Martello Towers & Batteries south of Dublin had overlapping fields of fire.

The Martello Towers in Dublin Bay were decommissioned in the 1840s but were rearmed again in the early 1850s with 24 & 32 pounder cannon as a precaution against a Russian attack during the Crimean war 1853 to 1856. Victor Du Noyer’s water colour (see page 2) dated 1866 shows the guns in place at Martello Tower Number Seven.

The last Martello Tower built was Fort Denison in Sydney Harbour, Australia to defend Sydney in the event of a Russian attack during the Crimean war. So, the Martello Towers are both Napoleonic and Czarist Towers.

Some of the decommissioned George 3rd Blomefield cannon were put to use as bollards outside the Beggars Bush Barracks in Ballsbridge where they can be seen chained and inverted alongside the public footpath on Haddington Road.

Viewing the Tara Hill Fortification.

As you approach the Martello Tower from the entrance gates you will see the fortified entry door to the Tower, 3 meters above ground level, with the Machicolation supported by three corbels above to protect the doorway below. This was entered by ascending a timber stairs that could be pulled up and into the tower during attack. To the right of the door at eye level you will see a bevelled hood over a blind gunpowder vent leading to the tower’s internal gunpowder store.

Just behind you is the coach house, a small stable with a loft overhead. A small lean to beside covered the coach. You will then see the Gunners cottage behind a railing. It is entered through a gated granite arch with steps down to the cottage and gunpowder store. The stone slabs on the ground once formed the roof of the store. They were removed in the 1980s by a prior owner.

You can visit the Martello Tower by descending granite steps and entering the Artillery Store. Be careful of the low headroom on entering. Once inside the artillery store, you will see the exhibition of Towers from Bray to Sandymount, with plans of fortifications, and certificates. Next you ascend the stairway leading to the murder hole shaft above entering the interior of the Tower, again please watch out for low headroom of opes and stairways.

The shaft/murderhole entered from the guardroom allowed the large 2.5 ton cannon to be hoisted by block and tackle to the second floor and then through a second shaft at the Machicolation to the Crown of the Tower. The two internal shafts were also murder holes or drop boxes from which the enemy could be shot.

You will see the living quarters with an open fireplace and light vent, the soldiers’ dressing room with light vent, and the gunpowder store and the inner side of the blind vent. The granite spiral stairway leads to the second floor where the soldiers slept.

On reaching the crown of the tower you will see the 18 pounder replica Blomefield cannon on its timber traversing carriage with the block and tackle attached. The rope is made from hemp to match the original. You will see a blocked drain exit on the channel behind the cannon which was a boiling oil hole. This allowed the burning oil to flow through tower wall and then through the machicolation and the corbels above the entrance door to deter the most enthusiastic attacker.

Outside the Artillery store/ Guardroom is a dry moat and a 3 cannon walled gun battery area surrounded by a steep glacis bank. At the base of the Glacis you will see 3 granite bench stones, no. 5 has WD, and 3 & 4 have marking of the crown of King George 3rd.

Restoration

Martello Tower Number Seven has been restored between 2004 and 2008. Sea gravel was used on the pathways. Pitch pine timber flooring was used and fixed with moulder brads. All cables and services were placed underground. The cannon was cast in UK in 2006 and proofed for blank firing by the Birmingham Proof Master. It was imported under EU licence. The timber traversing carriage was made by Mainmast Conservation. You can view a video of the casting in the Artillery store.

Niall O’Donoghue

Remarks at Niall’s funeral by Pól Ó’Duibhir, 13th May 2022

You have heard a lot of testimonials to Niall as a person from people better qualified to comment than me. I want to talk about the Tower. I want to talk about Niall and his magnificent project just up the road here.

I first met Niall around the year 2000. I had some maps and photos and we met in the Mont Clare Hotel during my work lunchbreak.

I had some familiarity with the site as it housed the Legion of Mary Hall where dances and other social occasions had taken place. In fact some couples married out of the Legion Hall, so to speak. The hall burned down in the early 1980s.

Anyway back to Niall.

I heard nothing from him after my meeting in 2000 until 2008 when I got an invite to come to the inauguration of the Tower. It was an amazing sight, a gleaming new tower and guardhouse where the previous oul’ piece of rubbish had been. The occasion was garnished by a troop of Napoleonic era Connaught Rangers in full gear and with loaded muskets which they fired. The cannon, which Niall had commissioned and installed on the crown of the Tower, was also fired. The ground shook and every house and car alarm in the Bay went off. It was magic.

Then over time I got to know Niall and was ever so impressed at his sense of purpose in taking on and seeing through this mammoth project. This was an achievement not just of national but of European importance.

And so it turned out to be when the Tower got a favourable mention from the European Jury in the Europa Nostra European Heritage Competition. When Bill Clements suggested to Niall that he enter the Tower in this prestigious competition I was a bit sceptical, given the huge size of some of the projects. But in the event Niall’s brother in law, Doug Rogers and myself set about trying to put some sort of an entry together. The questions on the entry form were very exacting, particularly on the European significance of the project. We managed that bit.

Then they wanted a report of the phasing of the project with costings. The only person who could answer that one was Niall. Niall said there had been no phasing. It was all done simultaneously in a mish-mash sort of a way. Sure, it was all first class quality, but no phasing. However it was a case of no phasing, no entry.

It took Doug and myself days of solidly beating Niall over the head before we got him to come up with some stuff. It was, of course, fiction in terms of phasing but it meticulously set out the hard graft involved in all aspects of this magnificent project. Then, in the run up to the adjudication we had a visit from the European inspector, presumably to make sure we hadn’t just entered a makey-up project created on Photoshop. He was very complimentary of the entry, saying that a good entry was when the inspector arrived to check out the real thing and felt he’d already been there before. He was also fiercely impressed by the project itself. Niall was so proud of the European jury’s reaction to the entry.

I mentioned Doug Rogers, without Doug and Sylvia, that’s Doug’s wife and Niall’s sister, there would have been no project. Among other things they did, they turned the UK Public Records Office in Kew inside out, digging out material and assembling briefs for Niall. Without them there would have been no Tower and no European recognition. Doug died two years ago, but not before he compiled an account of their work which then featured in the first virtual celebration of Bloomsday at the Tower in 2020 in the early days of the pandemic.

Bloomsday had been celebrated in-person at the Tower for some years previously, starting with readings from Joyce’s Ulysses by David Hedigan. After David’s death in 2015, my friend Felix Larkin was persuaded to give a talk on the Aeolus chapter in Ulysses and I thought if he can do it so can I. So, a later year I shamelessly pressed Joyce into service in my presentation of aspects of the history of Killiney and Ballybrack.

Back to the Tower itself. There is a list in the Europa Nostra entry of the lengths Niall went to in order to have the highest quality and most appropriate materials used in the restoration and of the care he took to get the right people to do the work.

I went through this aspect with Niall and he estimated that some 250 people were involved in the restoration. You can get some idea of those involved from the following listing of functions and activities:

- an architect and Martello Tower expert, scoping and advising on the project; [Paul Kerrigan]

- a retired international bank auditor and his wife undertaking extensive research in the UK National Archives and other UK archives, and searching out people to manufacture the cannon and gun-carriage; [Doug and Sylvia Rogers]

- a UK cannon specialist organising the provision of the cannon and carriage;

- a professional gun company undertaking project management in the cannon module, involving procurement of draughting, foundry and proofing facilities;

- specialists in armaments and fittings for listed fortifications making the cannon’s traversing carriage;

- the Royal Armouries, permitting copying of a King George 3rd Blomefield cannon and allowing the proofing of the cannon at the Armouries at Fort Nelson;

- the Birmingham Proof Master, proofing the cannon;

- a professional gunner providing training in gunnery and authorising Niall’s gunnery certificate. Yes, Niall himself was qualified to fire the cannon and proudly displayed the certificate in the guard room.

There were also inputs in the following categories: Archaeologists, Architects, rubbish and material removal experts, Stonemason, Sculptor, Carpenters, Electricians, Officials in the Government, Department of Justice, in the Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, and in the Garda Síochána.

And finally, my report of that inauguration in 2008 has now turned into a whole website on a wide variety of matters related to the Tower. Not forgetting the amazing model of the Tower which Niall’s son-in-law, Terry Murray, presented to Niall on father’s day. Niall was thrilled with it and brought it along to show people anytime there was a talk being given on the Tower.

So all this magnificence is here for current and future generations to appreciate and hopefully carry the work a stage further.

I’ll miss Niall, he was also a friend.

Martello Tower No.7 and the defence of Killiney Bay

Article by Pól Ó’Duibhir which was first published in Dublin Historical Record 2017 Vol.70 No. 2

Defending Killiney Bay

Britain & Ireland were almost continuously at war with France between 1793 and 1815. The British feared a French invasion. This included an invasion of Ireland and one of the places considered a possible target was Killiney Bay. [i] It was a deep water bay and within easy reach of the capital.

BACKGROUND

These fears became more acute from 1795 on and led to the establishment of a military camp in Lehaunstown adjacent to the Bay. The natives meanwhile had been getting restless and the camp was to have a dual function. It would protect the city in the event of increased rebel activity, or even rebellion, and it would defend the Bay in the event of a French invasion.

The camp was quite large consisting of at maximum around 4,000 troops, many of whom were militia and therefore not necessarily completely reliable – a feature to which we will return later. [ii]

By 1797 the authorities felt that a more professional approach to defending the Bay was required and they commissioned an émigré French royalist, Major La Chaussée to examine the terrain and make recommendations for its defence.

The major did a magnificent job analysing the Bay from a military point of view and he made very detailed recommendations on what needed to be done for its defence. The recommendations were acknowledged to be short term and implied that more permanent defences would be undertaken later.

It is not clear if any of the recommended works were actually carried out, but we will see later how his analysis fed into the location of the ultimate permanent defences, the Martello Towers and Batteries.

CHARLES LE COMTE DE LA CHAUSSÉE

The man

Charles Le Comte de la Chaussée was born on 28 July 1753 into a noble French family. [iii] At 16 years of age he entered the service of his King in La Grande Écurie. It is worth noting that to enter the Écurie your family had to be a member of the French nobility for at least 200 years. On graduating from his 3 year apprenticeship in the Écurie in 1772 he was made a sub-lieutenant in the cavalry regiment of Berry and some 5 years later a full lieutenant in the Company of Malvin. There is no further reference to his military record until 1815 when he is made a Chevalier of the Royal and Military Order of St. Louis. He retired from the army in 1816 with the rank of Captain, awarded with retrospective effect to 1791.

He left France in 1793, when the going got too hot, and between then and 1815 he devoted his talents to helping the British fight the French post-Revolution administration. I have been told that, at that time, a sense of brotherhood existed between armies that, in certain circumstances, proved stronger than loyalty to the nation. And in any event La Chaussée could remain loyal to his deposed King while serving the British.

On a more personal level, in 1787 he married Jeanne-Rufine-Françoise de Bourgogne [iv] and in 1792 the couple had one son Charles-Léopold-Marie de la Chaussée.

There appear to have been two distinct phases to his period in exile. He was certainly in Ireland in 1797 when he did his Killiney report and he did a similar survey in Bantry two months later. [v]

Apart from his surveying activities in Ireland in 1797 he was later involved in channeling funds from the British Government to French rebels (Les Chouans) in north west France who were attempting to overthrow Napoleon. In fact La Chaussée was involved in the funding of a failed attempt on Napoleon’s life which led to the execution of the perpetrators (Lebourgeois & Picot). So even though Napoleon never actually turned up here, the connection with Killiney is there through the failed assassination attempt. [vi]

The report

La Chaussée’s 1797 report is an amazing document. [vii] Although his orders were in the form of specific questions to be answered, he chose instead to do an overall report, analysing the vulnerability of the Bay as a whole and then setting out the defensive measures required. The report reflects the analytical mind of the professional soldier – it is concise, perceptive and to the point. It is possible that La Chaussée’s mastery of the English language was not great, at least as far as military terminology was concerned. Although his orders were in English, he chose to write the report in his native French.

As well as advising the fortification of some big houses, of which there were very few in the Bay at that period, La Chaussée suggested some revamping of the land at those points where the cliffs themselves did not provide an adequate defence. But the whole idea was to stop the French landing in the first place and to achieve this he picked three critical points in the Bay where big guns would be installed. The three main emplacements would be close enough to each other to ensure some degree of overlapping fields of fire.

The first emplacement was at the estuary of the Dargle river, the second at Maghera point at the centre of the Bay, and the third at the estuary of the Shanganagh river. [viii] Subsidiary positions were located at Cork Abbey, Shanganagh and Killiney Hill. [ix]

This is the oldest available photo of the tower which shows previous uses. It dates from around 1979. To be noted: (I) lean-to shed on left – this was the Rates Office and was also used by the Local Authority for storage, (ii) wooden building on right was Legion of Mary Hall, (iii) second floor door under machicolation bricked up, and (iv) new door cut at “ground” level.

The full set of positions took account of the need to fire on enemy troops should they succeed in landing. [x] The addition of the subsidiary positions also reinforced the seaward defences to some extent and enhanced overlapping fields of fire at the Bay’s most vulnerable points. [xi]

The availability of soldiers from the Lehaunstown camp was an integral part of La Chaussée’s strategy.

THE LEHAUNSTOWN CAMP – 1798 AND ALL THAT

The fear of a French invasion was proved justified when a fleet arrived at Bantry in 1796 but the troops did not succeed in landing due to bad weather. 1798 was a critical year in this story. In that year the French did actually land. But they turned up on the west coast and initially inflicted a serious defeat on the British before being eventually overpowered. This was the year of the actual rising during which the trustworthiness of the Lehaunstown camp was put in doubt.

It is known that the rebels had grandiose plans to subvert the camp to their own side and use the troops to take over the city. Central to that plan was Captain W Armstrong, who had been recruited to the United Irishmen and whose job it then was to line up a series of contacts within the camp who would organise the rest of the soldiers to come over to the rebels at the critical moment. Needless to say, in keeping with the total mess that was the 1798 Rebellion, Armstrong was a double agent and reported all his contacts with the United Irishmen to the authorities. He was later to give evidence against the Sheares brothers in their trial, detailing how they sought to subvert the camp.

All this much is known and set out in Pakenham’s The Year of the French. [xii] But there are some elements of the story which were not known to Pakenham and which I learned from reading Armstrong’s own diary. [xiii] For instance, Pakenham says that Armstrong was recruited in Byrne’s bookshop on the quays without any attention being paid to his political views and without these having been tested. Armstrong’s diaries show that he was only taken on after some extended political discussions and even then he was put through a fairly scary test of his loyalty subsequently.

This is the tower and the linked guardroom just before restoration commenced. Note the absence of the guardroom roof and the overgrown nature of the site generally. Note also the inverted V shape on the far wall of the guardhouse. This, along with a curved piece of wood discovered during the excavation provided the clues to the original method of suspending the guardhouse roof. Note also what appears to be a door in the near outer wall. This was a musket loop (like the one immediately on the left) which was converted to a window by the Council, along with another loop (obscured) on the right.

This occurred when he was invited to a meeting with the Sheares brothers in a house in the city on 14 May 1798. The meeting was unexpected and there was no obvious agenda. It is worth reading his diary entry to get the full flavour of what happened;

Monday 14th—[John Sheares] said some of our friends suspect that you are betraying us, I replied, I am surprised the idea could have entered their heads, well says he I am sure that you are true to our cause but some of our friends are so convinced of the contrary that I advise you not to come to our house this night for if you do I think you will be murdered. You know it would be very easy to do and bury your body at the back of our house, and nobody would ever think of looking there for you. I replied that so conscious was I of my own innocence that I would go to the meeting, we then parted, I went instantly to Lord Castlereagh and mentioned it to him, he said I don’t know what to say Captain Armstrong, we could not ask you to run such a risk, I replied, my Lord, I will go on with the business I have begun but I shall stay as short a time as I can; and do you cause the house to be surrounded by troops and if I am not out at half past twelve all will be over with me, I left him and went to their house according to appointment, when I arrived I was shown into the back dining room, there was a pair of candles on the sideboard and no other lights in the room, the end of sideboard was to the door, and at the further end of the room were five gentlemen sitting near the fireplace, I advanced, they rose and I walked over (more alarmed than I had ever been in my life, and in great agitation) and was presented by John Sheares to three of them, the other two were Henry and John Sheares, but their names nor mine were not distinctly pronounced, I took a vacant chair, and for some time a sort of conversation was held between each of his neighbour under their breath, a word of which could only now and then be understood. John Sheares who was next to me conversed more distinctly. Nothing of importance took place, I often looked at my watch, and at half past eleven I took leave and upon coming into the street I saw troops and constables and Major Sirr, I did not join him least it would create suspicion, and walked home. I am now of the opinion it was only an invention to try me, and that had I not gone I should not have been trusted any more. [xiv]

But the authorities did get a fright. They were no longer prepared to support the camp after the events of 1798 and it was closed in 1799. The Bay’s defences were thus, at least theoretically, weakened until the construction of permanent defences in 1804/5 in the form of the Martello Towers and Batteries. However in this intervening period the French were looking eastward and the British navy was more or less in control of the seas.

THE MARTELLO TOWERS AND BATTERIES

It was not till 1804/5 that the British got round to constructing the series of Martello Towers and Batteries designed to protect Dublin Bay, and a few other locations such as Cork and the Shannon, from the French.

There were some 28 emplacements built in defence of Dublin Bay, from Balbriggan to Bray. Of these 9 were involved in the defence of Killiney Bay alone. [xv] Amazingly, these super solid structures were constructed in about 18 months, using local materials and labour.

As part of the extensive renovations the tower had to be repointed and some elements replaced. The perimeter wall at the public roadway had to be repaired and the entrance moved. The scaffolding, shown here, was in place for 9 weeks.

Col Benjamin Fisher

The man behind this amazing feat was Col. Benjamin Fisher. He had come to Dublin in 1801 from Jersey where he had been in charge of the Royal Engineers in constructing similar towers. Before that he had served in Canada and the West Indies. As well as being a soldier he was an artist and we have some of his paintings from Canada [xvi] and one from Jersey [xvii] though I have not seen any from his Irish stay. He was a member of the RDS from 1801 to 1815 having been proposed for membership by General Charles Vallancey.

In locating the emplacements in Killiney Bay Fisher followed La Chaussée’s analysis and recommendations. He had, however, either given the matter further thought or had more resources at his disposal as he increased La Chaussée’s six emplacements to nine.

Of the three additional emplacements, two strengthened the defences of the two most vulnerable points where the cliffs were either absent or very low: No.8 was a battery at the junction of what are now the the Station and Strathmore Roads at the foot of Killiney Hill and No.1 covered the seafront at Bray. The third addition was a Tower and Battery on Dalkey Island. This both reinforced the defence of the Bay and also provided continuity with the more northern emplacements in Dublin Bay, which had not been part of La Chaussée’s brief.

Fisher was very much is own man and he did not take well to being hassled by bureaucratic superiors while he was on the job. This covering note speaks volumes:

These papers should have been earlier transmitted, but from the constant pressure of business, and the wont of regular assistance, it was not practicable. [xviii]

If that’s not telling your boss to get lost I don’t know what is.

Fisher seems to have been subject to depression, at least that is what you might deduce from the fact that, following his retirement to Portsmouth around 1812, he is reported to have died by his own hand in a water closet in 1814. A sad end for a man with such a distinguished career.

Anyway, back to the towers. The French never came to Killiney and after 1815 they were clearly redundant. The question remains of whether they served any purpose. All we can assume is that the French were aware of them as their construction was in what we would now call the public domain. [xix]

Nevertheless they had a brief revival during the Crimean War when they were re-armed. This presumably reflected a fear that the Russians were coming. That might seem a bit crazy to us but we should remember that 30,000 Irish soldiers took part in that war, [xx] that Ireland was part of the UK and would not be immune from attack depending on how the war went .

THE FATE OF THE KILLINEY TOWERS

After this, the towers were truly redundant but the military didn’t set about disposing of them till some years later. For example it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that they set about that in a systematic way.

The Township [xxi] of Killiney and Ballybrack, which also included Loughlinstown, was established in 1866 and by 1891 it had built itself a substantial Town Hall on Killiney Avenue. As with most bureaucracies its needs expanded and in 1897 it leased the site at Tower No.7, which was just around the corner from the Town Hall, from the military.

In advertising it for sale, the military had included this observation in the prospectus

The site is a most desirable building plot in what is at present a fashionable resort. [xxii]

It should be remembered that, quite apart from its beach as a destination for trippers, Killiney had become a fashionable residential area from the mid-nineteenth century with the arrival of the train. A city commute was now a reality and many important people took up residence in the area and commuted to town, taking a horse and carriage to the station and the train thereafter. We are inclined to think that most things in our own modern age are better than in the relatively primitive past, but the age of steam was no joke and it was as quick then to travel to town by train as it is today.

The final product, taken from the battery firing area. The restored guardroom is to the front of the tower. Note the curve of the roof. Note also the restored musket loops.

The Killiney and Ballybrack UDC eventually bought the tower site in 1909 and, to their shame, and that of their successor local authority, they spent the following century making an unholy mess of the place.

Not that some of the other towers have fared any better. By the end of the nineteenth century there were only four emplacements left in the Bay to be disposed of by the military, though there were many more in the wider Dublin Bay and up as far as Balbriggan. [xxiii]

The single most important factor that did for some of the original emplacements in Killiney Bay was the erosion of the cliffs that many of them were perched on. This was true of Towers Nos. 3, 4 and Battery No. 5, the last one of these being unusable as early as 1812.

The No.8 Battery was demolished with the coming of the railway in 1854 and some of its granite is still visible in the underpass which the railway company was obliged to construct to retain public access to the beach.

No.1 was demolished when the Bray esplanade was built, but No.2 behind Bray railway station is still there and was lived in by Bono at one stage.

No.6 on Killiney Beach close to the estuary of the Shanganagh River became a private residence and was lived in during my time in the area (1954-75). Around 1970 it was acquired by Victor Enoch, a prominent member of Dublin’s Jewish community and, according to himself, a Martello Tower aficionado. He added two out of place storeys to the tower which significantly reduced its value in terms of heritage.

To complete the picture for Killiney Bay, No.9 emplacement, the Tower and Battery on Dalkey Island, has been left to rack and ruin over the years but the Dún Laoghaire and Rathdown Council have plans to restore it and this, it is hoped, will eventually be part of a wider tourist attraction in the form of a Martello trail around Dublin Bay.

MARTELLO TOWER NO.7

Around 1970 the Council was exploring possible future heritage uses of the site, and among those mooted were a maritime or military museum or even just a platform for viewing the Bay. It is probably as well that these possibilities were not further pursued at the time as they would likely have involved the demolition of the “slated ruined lean-to on the seaside”. This referred to the artillery room which was in fact in a totally dilapidated and roofless state when the Council eventually parted with the property. But its total demolition would have obliterated what turned out to be vital evidence on the method of suspension of the slated roof. [xxiv]

The site at No.7 remained in the possession of the Killiney & Ballybrack UDC and its successor, Dún Laoghaire Borough, until 1987 when it was put up for sale. The consequences of its having been used as a dump over the previous century were beginning to intrude on its neighbours and by 1985 their complaints had surfaced at the level of national as well as local politics. Seán Barrett TD was both the local representative in the Dáil and also Minister of State at the Department of the Taoiseach. He was persuaded to lean on the Council to have the place sorted. [xxv] The Council’s eventual response was to pass the buck and put it up for sale.

To be entirely fair to the Council, the site had not been exclusively a dump over the previous century. The local rates office was located in a lean-to at the tower and in 1939 the local branch of the Legion of Mary got permission to build a wooden hall which hosted their meetings and occasional dances. The hall burned down around 1981. The existing gunner’s cottage had also become the residence of the Council Lamplighter. And had it not been for the storing of the Council’s unique horse drawn vacuum tanker in the shed beside the rates office, this wonderful piece of equipment, accidentally rediscovered in 1977, would have been lost forever. It is now in the National Transport Museum in Howth. [xxvi]

One particular use of the site has been kept very quite until now. This happened in 1954 when the tower was used to store one thousand pounds of gelignite and detonators. These were to be used in a major sewerage works being undertaken by the Borough. The neighbours were not consulted and were unaware of this, though the agreement of the occupants of the site [xxvii] was sought and received.

In any event the Council decided to pass the buck and in 1987 the site was sold to a private individual . It appears that, from a heritage point of view, the only condition attaching to the sale was that the purchaser would maintain the site and not let it deteriorate beyond its then current condition. A more deteriorated condition would have been hard to envisage.

The State of the Place in 1987

It is important to remember that the site as sold by the Borough was very different from that which had been occupied by the military during most of the nineteenth century.

- All the metal elements (in particular the cannons) had been removed when the tower became obsolete (by the last quarter of the nineteenth century). So far, only the cannon on the crown of the tower has been replaced. The new cannon was freshly cast in England but from a mould created from a cannon of the period. Needless to say the Irish Department of Justice got a right fright when they realised that the requested arms import permit was for a full size (newly cast) working cannon from the Napoleonic era.

- The artillery room had been destroyed and all that remained were the exterior walls. This was an important loss in the context of the restoration as the original plans were not available and the room had some unique architectural features which could only be established by a careful examination of frugal pieces of remaining evidence and photographs from as late as the 1960s.

- The coach house was reduced to its bare walls,

- the gunner’s cottage and magazine store had been completely demolished.

- The site was carrying up to nearly five thousand tons of rubbish.

- The original entrance door to the tower at first floor level had been closed up and a new entrance made at ground level in the course of the modifications required for the storage of the explosives, referred to above..

- Two of the musket loops (relatively small slits) in the outer wall of the artillery room were converted into full size windows. I mention these particularly because when Niall wanted to restore the windows to their original function as musket loops, he encountered opposition on the grounds that the windows had now become part of the heritage and could not be interfered with. He eventually won out on that one. It’s a wonder they allowed him to remove the century’s accumulated rubbish which would have had an almost equal claim to heritage status.

RESTORATION OF TOWER NO.7

The new owner did nothing with the site and ten years later, Niall O’Donoghue acquired it. It was not long before Niall, who has a keen sense of history, started researching the possibility of its restoration. Given the state of the place you can appreciate that restoration would be a Herculean task which would demand all of Niall’s sense of purpose. However, had he realised the enormity of what lay ahead of him we might not have the magnificently restored site we have today.

Every effort was made to ensure that the restoration would be as true as possible to the site as it was in the Napoleonic era.

Plans

All of this work was accomplished without any access to the original construction plans. These appear to have vanished but such must have existed as the complex construction of the towers could not have been achieved without them. This meant, however, that in drawing up plans for the restoration of the site regard had to be had to similar structures elsewhere, where such existed, and to such evidence as emerged during the initial clearing of the site.

A good example of this was the restoration of the slate roof over the artillery room. The architectural consensus was that pillars would be needed in the centre of the room to support the roof. This would have been most unsatisfactory and an impediment to moving equipment within and through it. Luckily Niall spotted a clue to the original suspension method on the inside of the remaining wall and this was further refined on the basis of a piece of curved wood found in the remains.

In brief, the physical onsite work included:

- clearing the accumulated rubbish, referred to earlier. It took 230 20 ton truckloads of rubbish each truckload costing €1,600 as the rubbish had to be sorted by hand due to the “heritage” nature of the site

- renovation and repair of the tower which was in a very dilapidated condition. This included necessary repointing and replacement of some missing pieces. The original door had to be restored and the new door blocked up. A completely new internal ceiling/floor had to be installed where the original had burned down.

- the coachhouse had to be almost completely restored. Only the walls remained.

- The gunners cottage had to be built from scratch. It had been completely demolished. Only the footprint remained and the original had to be built on this in its original style

- a new entrance to the site had to be constructed

- the boundary wall had to be determined and reconstructed

- the 18 pounder cannon (specially cast and proofed in England) had to be imported and installed on the crown of the tower. [xxviii]

- the gun carriage (specially made in England) also had to be imported and installed on the crown.

People

In all, Niall estimates that some 250 people were involved in the restoration. See list referred to in Pól’s eulogy above.

There were also inputs in the following categories: Archaeologists, Architects, rubbish and material removal experts, Stonemason, Sculptor, Carpenters, Electricians, Officials in the Government, Department of Justice, in the Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, and in the Garda Síochána.

Materials

Materials as near as possible to the originals were used where they could be procured. Some examples:

- gravel from Kilmore Quay in Wexford, as being the nearest thing to the original available.

- molder brads (nails) were obtained from Scotland

- blocks and tackles matching the original design were procured

- hemp rope was used to replicate the original for the block and tackle.

- flooring and joist supports came from old pitch pine beams from a brewery and were cut down to match the originals.

- an original magazine door (which is currently a display item as the magazine store has not yet been restored). [xxx]

In all of this work, great attention was paid to detail. For example, the stonework was completed by qualified stone masons using Irish granite on site for wall building with recommended lime mortar. The tooling of replacement external granite stonework to match the original granite curved and battered walling was completed successfully by the noted Irish sculptor Padraic MacGowran and the battery walls and the arch to the Gunner’s cottage were completed by a professional conservation and restoration company.

Inauguration (2008)

By 2008 sufficient work had been accomplished to permit the inauguration of the Tower and cannon, though there was still much potential work to be completed, such as the restoration of the magazine store and the arming of the artillery plain with three twenty four pound cannon.

EPILOGUE

Europa Nostra

In the course of a visit to the tower, Colonel Bill Clements suggested that the project might appropriately be entered for the Europa Nostra heritage competition. This is a prestigious annual competition backed by the European Union. The fact that the work was not fully completed allowed Niall to enter it for the 2014 Heritage Awards. While not winning one of the major prizes, the project merited a special mention from the jury which is considered a major achievement. [xxxi]

Events

There have been a number of events at the Tower since its restoration.

The cannon has been fired on a number of occasions including one spectacular firing in the dark welcoming in the new year of 2013. It is probably the only Martello cannon in these islands ever to have fired on a French frigate though this was not in anger. [xxxii]

There have been three Joycean readings/talks on Bloomsday, in 2012 and 2014 by the late David Hedigan and in 2017 by Felix M Larkin.

There has been one wedding, so far, at the Tower. And a number of gigs

Visitors

There have been many visitors since the restoration. In terms of numbers, most would have been during Heritage Week, but there have also been visits by groups, including the Fortress Study Group, the Scouts and the Defence Forces Archive. Individual distinguished visitors have included Enda Kenny, Colonel Bill Clements, both Bruce Davis and Ruth Adler, when they were the Australian Ambassador, Eoghan Keegan when he was Dúnlaoghaire and Rathdown County Manager, and Philippe Milloux, Director of the Alliance Française in Dublin on his first expedition following his being knighted by the French Government on the previous evening.

Interpretive centre

In addition to the purely restorative aspect of the site, a new structure is well on its way to completion. Its design fully respects the integrity of the site and, when completed, it is intended to house, inter alia, an interpretive centre where artifacts and visual material can be displayed, and a functions room for talks and seminars and the like. Hopefully this will contribute to deepening the public’s appreciation of the site and its history.

The Tower already has a dedicated website[xxxiii] and a presence on Facebook[xxxiv] and Twitter[xxxv].

So, all being well, the Tower may have as significant a future as it had a past.

[i] The Defence of Dublin, Kevin Murrray, Irish Sword Vol. II p 332-3

[ii] I have dealt in further detail with the camp in my essay The French are on the sea …A Military History of Killiney Bay from 1793 to 1815 in Irish Sword, Vol. XII, No. 46, Summer 1975, p 55. An online version of that article can be found here http://photopol.com/articles/french.doc accessed date. 30/7/2017

[iii] P Louis Lainé, Archives Généalogiques et Historiques de la Noblesse de France Vol. IV Paris 1834 under De La Chaussée p10 also online at https://books.google.ie/books?id=iFcoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR63 (XIV at bottom of page) accessed date 30/7/2017

[iv] She was a 14th generation descendant of Jean le bon, King of France 1350-64. http://dynastie.capetienne.free.fr/05Gaston_Sirjean/10La_2eme_maison_de_Bourgogne/Generations/13eme_generation/13006_12009.html accessed date 30/7/2017

[v] Reports and Plans of Major, Le Comte De La Chaussée, Bandon 31 March 1797 National Library of Ireland Ms. 809

[vi] Victor Maingarnauld Campagnes de Napoléon Vol 2 Paris 1827 p417 https://books.google.ie/books?id=8kdjAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA417 accessed date 30/7/2017

[vii] Reconnoisse Militaire de la Baye de Killeeney 11 Février 1797 by Major La Chaussée (B.M., Add. MSS 35, 919). As well as the copy in the British Museum (now the British Library) which I worked from, there is also a microfilm copy in the National Library of Ireland (NLI n.915 p.990). The report can be read in its original French, in manuscript at http://photopol.com/la_chaussee_rec/la_chaussee_ms.pdf , in typescript at http://photopol.com/la_chaussee_rec/la_chaussee_type.pdf , and in my English translation at http://photopol.com/la_chaussee_rec/la_chaussee_trans.pdf (accessed all date 30/7/2017).

[viii] These points correspond with the later Martello Tower positions Nos.2, 4 & 6.

[ix] These points correspond with the later Martello Tower/Battery positions Nos.3, 5 & 7.

[x] It is interesting that Joyce claims that the battery at No.5 position was in the wrong place as the cliffs rose in front of it on the seaward side. (Weston St. John Joyce, The Neighbourhood of Dublin, Dublin 1939, p62). It did turn out to have been in the wrong place but not for that reason. It was there primarily to fire on troops who might succeed in coming ashore at the Shanganagh estuary, but it was too close to the cliff edge and erosion made it unusable as early as 1812.

[xi] In the early stages of the research, in the 1970s, only La Chaussée’s written report was available but some 30 years later his maps were found and these can be seen online. His general map, including inland features http://photopol.com/dca4/la_chaussee_map.jpg and the purely coastal map, including fields of fire http://photopol.com/dca4/lc_map2.jpg accessed both date 30/7/2017

[xii] Thomas Pakenham, The Year of Liberty London, (1969), 81, 90, 95

[xiii] T.C.D., MS 6409/10 [pencilled pagination pp 55-64]. I have reproduced relevant extracts from the diary along with my own comments in a note Captain John Warneford Armstrong and the Sheares Brothers in Irish Sword, Vol XIII, No. 50, Summer 1977, p 70 which is also available online at http://photopol.com/articles/sheares_notes.doc accessed date 30/7/2017

[xiv] This extract is published by kind permission of the Board of Trinity College, Dublin.

[xv] Two of these consisted of stand-alone Batteries without a Martello Tower, Nos, 5 & 8.

[xvi] Although dating from the period 1785-96 they were only recently (2003) discovered in a cellar in Balliol College Oxford. https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/10486/lot/149/ accessed date 30/7/2017

[xvii] Mont Orgueil Castle, headquarters of Philippe d’Auvergne who managed the British Government’s spy network in north west France from Jersey. http://www.atelierlimited.com/art_detail.php?id=AT711 accessed date 30/7/2017

[xviii] From the Engineer’s Office, 28 July 1804 (effectively Fisher to his superiors). UK National Archives, W0 55/962 261613

[xix] General Vallancey had been one of those who questioned French officers captured after the ill fated Bantry, during which questioning he learned that Bantry, despite its isolated position, had been chosen in preference to Cork which the French knew to be well defended. Monica Nevin, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol 125 (1995). pp. 5-9 http://www.jstor.org/stable/25549787 accessed date 22/05/2014. So it’s not impossible that similar considerations regarding the towers might have had at least a marginal effect six years later in deterring a French invasion.

[xx] David Murphy in History Ireland Vol 11 Issue 1. Also available online at http://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/ireland-and-the-crimean-war-1854-6/ accessed date 30/7/2017

[xxi] This later became an Urban District Council (UDC) under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

[xxii] Source is military typescript document reporting on the letting and unsuccessful attempted sale of the site in 1890.

[xxiii] The four in Killiney Bay were Nos. 2, 6, 7 and 9.

[xxiv] Report to the Council’s Senior Architect dated 28/5/1970

[xxv] Letter from Seán Barrett TD & Minister of State to the Council’s Housing Department 31/1/1985.

[xxvi] http://nationaltransportmuseum.org/ubv005.html accessed date 30/7/2017

[xxvii] The lamplighter and the Legion of Mary.

[xxviii] The story of the search for a cannon and the eventual bespoke casting and proofing are a story for another day.

[xxix] Doug and Sylvia Rogers. They deserve special mention as they were the backbone of the extensive, and very productive, research in Kew (UK National Archives).

[xxx] This is the actual door illustrated in Victor Enoch’s booklet on Martello Towers. Victor J Enoch, Martello Towers of Ireland, 1975, self-published.

[xxxi] There is a page on the Tower’s website devoted to this. http://photopol.com/europa/index.html (accessed date 30/7/2017) and you can read the entry document online. This contains further background and detailed information on the project.

[xxxii] http://photopol.com/martello/no7_5.html accessed date 30/7/2017

[xxxiii] http://photopol.com/martello/no7.html accessed date 30/7/2017

[xxxiv] http://www.facebook.com/martellotower accessed date 30/7/2017

[xxxv] http://www.twitter.com/martellotower7 accessed date 30/7/2017