Introduction

Killiney townland, village and general district, to which this website is dedicated, derives its name from the church of Cill Iníon Léinín. Probably the site of the earliest human habitation in the area its significance lives on to the present day. In this article we have gathered many of the notable scholarly investigations and reproduce them here to give as comprehensive a history of the church and the surrounding area as possible.

In particular we are delighted to publish, for the first time, an excerpt from ‘Killiney Surroundings’. This work consists of a collection of essays and notes compiled over a period of forty years by the bookseller William Fernsley Figgis, a native of Killiney. It appears that Figgis began to compile his history of Killiney sometime around 1916 and continued to work on it until his death in 1956. The section which we have transcribed for this article covers the earliest history of the church and was contributed by Charles McNeill (editor of Archisbishop Alen’s Register).

Also transcribed here are excerpts from papers written by the distinguished scholars, W.F. Wakeman (1892) and J.P. O’Reilly (1904). We would like to thank Timothy King for contributing the summarised history below which provides an overview of the main points pertaining to the ruined remains of the church.

Historical Summary by Timothy King

Killiney is an English adaptation of the Irish, Cill Iníon Léinín, which means “Church of the Daughters of Léinín”. Léinín was a local chieftain who was converted to Christianity, and together with his daughters founded a monastic community on what is now Marino Avenue West. Sources vary as to whether there were five, six or seven daughters, but such variation can be found for virtually all numbers and dates before the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169-70. George Petrie, the most famous antiquarian of early Victorian Ireland, claimed in his 1845 book, The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland anterior to the Anglo-Norman Invasion, that the original church was contemporaneous with the first church at Glendalough, and therefore dated back to the sixth century. This would be consistent with the fact that Léinín was also the father of St Colman, an early Irish poet who died about 604. St Colman founded a monastic settlement in Cloyne, Co Cork that eventually evolved into the diocese of Cloyne, whose Cathedral in Cobh is dedicated to him.

The current ruined Church dates from the eleventh century, with a sixteenth century aisle on the Northern side. At some time before the English conquest the church came into the possession of (the phrase used by historians is “confirmed to”) the Priory of the Holy Trinity, whose lands stretched from Murphystown, at the foot of Three Rock Mountain to Killiney. After the dissolution of the Priory in 1539, control over the church passed to the Dean of Christchurch Cathedral. It is said to have been in good repair in 1615, but by 1654 it was roofless.

Petrie is reported to have called it a “ruin in perfection” and to have expressed a wish to be buried there. Since he probably knew more about Irish ruins than any other man of his time this was quite a compliment. Petrie was a distinguished water-colourist and collector of traditional music, who headed the Topographical Department of the Irish Ordnance Survey for more than a decade and has been called the “father of Irish archaeology”. Most of his writing was before the railway and its related wave of housebuilding arrived in Killiney, so that the church stood isolated at the top of a grassy slope stretching uninterrupted down to the Bay, and lit by the first rays of the morning sun; what more could one ask of a burial spot? In the event, however, Petrie was buried in Mount Jerome cemetery in 1866, but there were occasional later burials; the last was in 1951.

The church is now looked after by a small committee, and a small grant from the Dun Laoghaire Rathdown Council helps to keep the churchyard in its present excellent condition. Even though now surrounded by houses, it is very well worth a visit. The gate to Killiney Ancient Church & Graveyard is normally locked. The key may be borrowed from the Café in Killiney Dart station (A small deposit is required). Please check café opening hours before visiting. Other enquires regarding access can be emailed to killiney.ancient.church@gmail.com

Graveyard Inscriptions

You can read our article which has transcriptions of a number of gravestones in the old churchyard HERE

Cill Iníon Léinín as described in ‘Killiney Surroundings’ by Charles McNeill (editor of Archbishop Alen’s Register)

PAGAN AND CELTIC

Killiney – Cill Inghin Lenin, Church of the daughters of Lenin, receives its name from the ancient church, the picturesque ruins of which are familiar to all who frequent the neighbourhood.

It seems appropriate that any account of Killiney should begin with a description of the venerable building from which it derives its name and identity. It presents indeed a story of sufficient antiquity, and yet, were we to begin at the true beginning there would be something to tell of certain convulsions of nature in some remote period of bygone ages which would make any records of the Christian era modern indeed in comparison. To these shape-squeezings of nature we owe our hills, our beautiful cliffs and all that goes to the making of Killiney.

We now return to our Ancient Church which occupies a commanding position perched upon its low eminence overlooking Killiney Bay. It is of very early date; probably 6th or 7th century and exhibits all the architectural characteristics of an age which closely followed on the period of the advent of Christianity to Erin.

“As for access to the church, one need not worry much. Those of us that were raised in the country were accustomed to see people on Sundays coming in on all sides through fields and across fences. There must still, in places, be ‘Mass Paths’ as there were 50 years ago, that went through demesnes and in front of mansion-houses for a privileged occasion. The earlier the date the greater would be the freedom of passage. In the case of Killiney, assuming the present parish (of no more than about 2 square miles) to retain practically the ancient district served by the church, the old site was unusually central, and could be reached on foot by the remotest parishioners within 20 minutes. “Not many years ago, the time-stained teampull or cill was approached from the main road by a rude boreen on the left hand side of which stood a hoary thorn tree which must have been several centuries old; beside it was a carn, station, or alter – alas, they have been totally disappeared before the march of improvements, as has also the original ‘mur’ or well-marked earthen rath by which the venerable cemetery was environed.’

It is recorded that George Petrie and old Mr. Wakeman loved this ancient sanctuary. A board facing the passer-by bears the following legend:-

“Here for a thousand years God was worshipped by Gael, Dane and Norman, united their one faith. Many of them rest beneath the shade of its venerable and hallowed walls.”

NOTE 1. Cellingenlenin i.e. Cill Ingen Lenin, the Church of the daughters of Lenin, a name now translated into Killiney, a church on the seashore between Dalkey and Bray Co. Dublin. The ruins of this church are in fair preservation. The west door and chancel are fine specimens of ancient Irish architecture, and are supposed to be as old as the 7th century The interior dimensions of the church are 35 feet. The nave measures 12’8″ to the chancel and 9’6″ in breadth. An addition was made on the north side of the chancel in the 13th century. The west door measures 6’1″, height at top 2′ and at the sill 2’4″: the masonry is of a very ancient type. The chancel arch is in the style of the west door. It is 6’6″ high, the width at the sill is 4’10 ½ , and 4’7″ at the spring of the arch. The eastern window is square-headed, and has, like all the other windows of the church, a very wide splay, a sign of great antiquity in Irish Ecclesiology. In 1615 the church was in good repair; in 1654 it was roofless. Note from Moran’s Edition of Archdalls’ Monastican Hibernicum Vol.1 p 330

NOTE 2. The daughters of Lenin are variously given in the old martyrologies. According to the Rawlinson Mss. they were 7 in number, viz. Aigleen, Machain, Liuden, Druiden, Luicell, Rimthech, Brigit ‘oga sin uile excepta prima’, virgins all except the first. In the Martyrology of Donegal the sisters are given as Druigen, Luigen, Luicill, Macha and Riomtach, and they are described as sisters of Brighit, daughter of Lenin. In the Martyrology of Gorman the dedication is simply ‘the virtue of Lenin’s active daughters’. They were venerated on 6th March (See O’Hanlon’s lives of the Saints.)

NOTE 3. There can be no doubt that it was our Killiney church that was associated with Lenin’s family, (of Killiney, Co. Kerry we need not enquire). In the Annals of the Four Masters the following passage occurs – 738 A.D. Dubhdothra (The Black man of the Dothair, now River Dodder), Lord of the Ui-Briuin-Cualain was mortally wounded. O’Donovan in his note on this passage says ‘A sept giving name to a territory comprising the greater part of the barony of Rathdown in the present Co. Dublin, and some of the north of Wicklow.’ The Church of Cill-Inghine-Lenin, now Killiney, is set down in O’Clery’s Irish Calender as in this territory.

KILLINEY:

The Church was confirmed to St. Lorcan Ua Tuathail in 1179 by Pope Alexander (along with other Secular Possessions) as Cellingenalenin. It was confirmed almost immediately by St. Lorcan to the Cathedral of Christ Church (with the town) as Cellingin Lenin. The Church had been granted in 1038, with Clonkeen for the support of the new Priory of Holy Trinity, by Donough, the Irish Chieftain of the district, of the family of ui Dhonnchadha.

It may be taken then that the community of Killiney had ceased to exist before 1038, namely, during the Norse raids. What was it before that time?

I take it that Lenin and his daughters became Christians early in the 6th century, and that the community of Tully were responsible for their conversion. Lenin bestowed the site and lands for a church and its support. The church was built near an earth fort (long since disappeared) enclosing a cairn of some chieftain. There was a pagan settlement at the site of the so-called Druid’s Chair.)

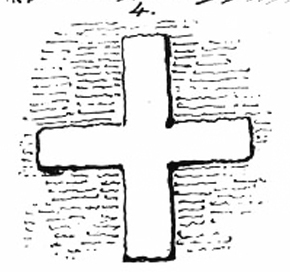

The figure of a Roman Cross under the lintel of the West Door is important; it shows that the church was saned “Blessed” or dedicated by some important ecclesiastic (St. Patrick for instance, marked several churches with a cross.) The daughters of Lenin, having set up their church, apparently got one of the Tully community to dedicate it for them and mark it with a cross. There is no doubt that the church was for a community of nuns; the entry in the Martyrology of Donegal at 6th arch shows this. It is quite reasonable to suppose that the daughters, or some of them, were trained in the religious life at Kildare. Their brother was St. Colman of Cloyne, died c. 600. This would place them near, if not in, the life time of St. Brigid of Kildare A.D. 451-525. I take it that the community disappeared during the Norse raids (probably 9th century as Rathmichil disappeared. Both churches, and Tully, were enlarged in the 12th century.

NOTE 5. Killiney, Co. Dublin.

Killiney, Co. Dublin is identified with Cill-Inghin-Lenin in the territory of the Uí Briuin Cualann, mentioned in Martyrologies (Gorman, Donegal) at 8 March, A late note in Gorman has for interpretation “filiae Lenini in Tamlacht,” that is, Killininny near Tallaght, which is wrong. Killininny was Cill-inghan-nAilello, and was not in Ui Briuin, but in Ui Cellaigh Cualann.

(For these two districts as royal manors (so much, that is, as was not church land, see Mills in J.R.S.A.I. XXIV, 170, 171, 173; and for the Irish references generally, see Hogan’s Onomasticon.)

A reason for naming the church Cill-inghen-Lenin may have been to distinguish the patron, whose name was Brigit, from St. Brigid of Kildare; but I am not without a lurking notion that these inghen churches were so named as original nunneries, a necessary consequence of their being founded and governed by women. The number in the Dublin diocese is remarkable. Besides the two above were “Ecclesia Filiae Tolae” the site of All Hallows and of Trinity College and Donabate, which me judice is Tech-ingen mBaile beside Swords (29 March), to pass over Call-ingen in Ui Dunchade as uncertain. Ingen means not only daughter but an unmarried woman, a maiden, and here, it seems a nun, much like the old English Minchin from which “Minchin’s Mantle”, grounds of the nuns of the Hogges, behind Grafton St., and Mincing Lane in London. Small and obscure houses of women inevitably dwindled away; their churches and possessions passed to other hands. Killiney at the time of the English invasion belonged to the Canons regular of Christ Church as is seen in the grant of c.1178 no. 364 of Christ Church Deeds from an inspeximus where the name is printed – LEAIN, but correctly in No. 6 – Lenin and also in Alexander 111s confirmation of 1179. Its position in these documents – Tilachachain (not M) Cellingenalenin, Celltucca, is pretty accurate geographically.

That there were parishes and parish churches in Ireland before the Invasion is clear enough; there are provisions in the Ancient laws concerning the incumbent’s obligations to administer the sacraments to his people. But how was that flock constituted? This question has not been thoroughly studied. Most writers, brought up in the system of defined boundaries, a system derived, no doubt, from the old Roman Empire, cannot imagine other conditions. But the Irish State (not disregarding territories where men must live) was built up on kindreds and communities, and so, as I conceive it, the congregational structure of our primitive church must have been. Our bishops down to the 12th Century, were bishops of the Leinstermen, the Munstermen, the Connachtmen, and lesser political units; their dioceses were the territories of their flocks and were limited accordingly. So ingrained was the notion of homogeneity that when a Saxon Ecclesiastic got a settlement at Mayo, Mayo of the Saxons, it was taken as a matter of course that he and his community should retain their extra-territorial standing, and a bishop of Mayo did actually sit in a synod of English bishops. Accordingly there was, at first, no violence to Irish sentiment in the refusal of the bishops of the Norse settlements to take their place with those of the Irish, and to accept the decisions of Irish councils, preferring kindred Canterbury.

Bearing these and similar considerations in view, there will appear to be three distinct periods under very various conditions for local or parish churches of the Dublin area; the Irish period, during which, if my impressions are correct, Killiney would be originally a community of nuns, without parochial responsibilities, unless, perhaps, to the tenants of its lands, if it had any, for whom it might have to provide. If the community of nuns died out or was extinguished in times of violence, its place might be taken in that respect by the ordinary local ecclesiastics of the rural commune, as indicated in the Laws.

The second period, of the Norsemen, is more shadowy still: they continued to be pagans for a considerable time after they had reduced the Dublin district. But for all the anti-Christian rage we read of, the indications are that they left the tillers of the soil as they found them; they did not destroy the great abbeys, whose doings still find annalistic record for a time, and when the abbeys disappear, their lands are preserved to the church and they endowed the See of Dublin with fine estates of Lush, Swords, Finglas, Clondalkin and Rathmichael. “Callinginilenin with its church” forms in 1178 part of the endowment of the Canons of Christchurch. From this form of words it can be deduced that the church had, through every vicissitude, retained some part of its original endowment, and if the records had not perished in the disastrous explosion of ’22, the residue might still be traced. Speaking generally, my observation is that when a church was founded, more hibernico, a piece of land nominally a carucate (120 acres of arable land over and above wood, meadow and pasture’) was assigned as its endowment to maintain the church and the priest that served it. So much land might even now, as agricultural land not growing villas, be a competent provision for a single cleric.

Contributed by Charles McNeill. (editor of Archbishop Alen’s Register)

MEDIAEVAL RECORDS

Between the time of Lenin’s daughters and the earliest date recorded of Killiney or the neighbourhood, there is a long gap of many generations of complete oblivion.

“In 1176 Pope Alexander III issued a bill taking into protection the diocese of Dublin and at Archbishop Laurences’ request confirmed to him its possessions.” (1) Amongst the parishes mentioned are Cellingenalenin, Balemochan (not known) Ballyogan, near Carrickmines (Loughlinstown).

In the same year the church of Killiney was, amongst other possessions, confirmed to Christ Church by Archbishop O’Toole. On 2nd July 1186 Pope Urban III ‘Confirms to Holy Trinity Church (i.e. the Priory of Christ Church) Cellingini Lenin with its Church. (2) This was again confirmed by Pope Celestine III in 1192, 31st January (3)

In about 1240 Luke, Archbishop of Dublin confirms to the Priors and Canons of the Holy Trinity, Dublin…Klunken (Clonkeen) with the Chapel of Carrickbrenan, Kylebekenet, Dalkey), Killiney, Telach (Tully) and the chapel of Stachlorgan (Stillorgen).

In 1368 we read of one, William Topper, cellarer of the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, Dublin, receiving money for buying corn and oats. He accounts for receipts from the treasurer Robert Hacket for tithes of Balitilyst (Tipperstown) for tithes of Kylleny. (4)

From some of the entries in the Christ Church Deeds we can form an idea of the kind of life in the neighbourhood of the present Killiney. Thus we learn that one August 19th 1344 ‘there were reapers there of the customary tenants, 15 from Killiney for whom John Chamburleyn, Bailift of Clonkeen accounts in bread and ale from stock. In flesh bought for same 3d. (5) Also he accounts to the servingman of Oliver Hacket watching the tithes of Killiney and Loughlinstown 2s.

The Hacket family flourished in the district in the 14th century. John Hacket was one of the most frequent visitors to the Priory, and was the owner of a mill near Clonkeen…. he held also some position for which he received a fee of 20/- from the Priory. He had been a leader of the county’s levies against O’Byrne; and was one of four keepers of the Peace appointed by the Viceroy and Council to assess the men of the county for service in the field? Three other members of the family, William, Oliver and Thomas Hacket are mentioned in these accounts, chiefly as helping in a neighbourly way at the manor of Clonkeen. The name is still preserved in the district, in the townland of Hacketsland, lying to the south of Killiney.

- See calendar of Archbishop Alen’s Register. Ed.Chas. McNeill.

- Christ Church Deeds 6 and 8

- See also Christ Church Deeds 44, 52, 53, 379.

- Christ Church Deeds 51.

- Christ Church Deeds 244.

- Account Roll of the Priory of H.T.Dublin 1337. Ed. by James Mills RSAI. Sweetman’s Calendar of Documents relating to Ireland.

Clonkeen, Clonkene, Klunken, Clonken – the demesne lands of this manor lay around Kill of the Grange. The tenants who owed service to it occupied holdings from Murphystown to Killiney inclusive. In an entry (date about 1326) we read :- There are cotters there. And they shall work in harvest for 3 days: And each of them shall do divers other works with ploughs and carts or cars which are worth by the year 3/-‘.

A Rental of Holy Trinity Church (circa 1326) contained a list of tenants, stating whether farmers or cottiers and giving their rents both in money and kind, the quality of land, rent per acre, etc. The customary rents included performing suit of Court, ploughing the lands of Holy Trinity at the different sowings: hoeing, reaping and carting the corn, saving the hay, furnishing hens at Christmas, and geese at Michaelmas, and the customary Talbdl when the tenants brewed.’

In the 16th century it would seem as if the returns of these lands, or at all events the collecting of the revenue from them, was leased out to individuals and in three of these leases we read of the town of Kylleneen (or Killineene).

In 1586 a grant was made to Sir Morgan Byrne of Killenyn Co. Dublin chaplain, the cures of the churches of Killenyn and Dalkie with the manses, glebe lands and fishing belonging thereto, during his life, grantee administering Sacraments to the Parishioners, building and keeping the manses in repair, and discharging all the charges affecting said cures.’

In deeds dated 8th August 1538 and 1565 respectively we read of a William Welshe or Walche as lessor, and in 1586 of a James Garvey, probably a relative of the Primate of that name.

1296. Ralph le Rough, of rent of Balimacorus 6/-. Thomas le Leghe of issues of the lands which belonged to Christiana de Mariscis at Killenen 40/-. Thomas de Leghe of issues of the lands of Christiana de Mariscis at Killegien 20/-. 1301. Gross receipts of Richard de Bereford, Treasurer of Ireland, the Vill of Killenien for escape of Henry Pudding 10/-. of rent of same vill 20/-.

Walter, Archbishop of Dublin, confirms to Holy Trinity Church….. the churches of St. Fynton of Clonkene, St. Brigid of Stalorgan, St. Brigid of Tyllagh, the Church of Kylleny, Chapel of St. Brigid near Carrigkmayn, with their tithes…. and.. the towns of Kylleny, Ballyloghan (Laughanstown). 17th Sep. 1504.

John Alen Esq, Chancellor, George Archbishop of Dublin, William Brabazon Esq. Subtreasurer, ordain that Holy Trinity Church, having been secular at its foundation, its ministers shall in future be regarded as secular priests and wear secular habits; that it shall have a Dean, Precentor, Chancellor and Treasurer, like St. Patricks: that Robert Paynswicke alias Castell the Prior shall be dean and that he and his successors shall enjoy Clonkene for his dignity, and the church of Glasnevin for his prebend with the temporalities in Dalkeyn, Killeny, Balliloghan etc. and the church of Killiney etc. (1)

Lessors in No. 1163 lease to William Walshe otherwise called Wm. Mc Howell or Killiney, gent, the town of Killenyn in the marches of Dublin, and the temporalities thereof, for 31 years at a rent of £1.6.9. dated 8th August 1538.

Lessor in no. 1298 lease to William Walshe McHowell of Kylleneen, gent, the town of Kylleneen in the marches of Dublin for 31 years, rent 26.8, with covenants for re-entry, repairs, watch hens, and half for heriots dated 5th Jan. 1565.6. 8th Elizabeth.

KILLENY. ARCHBISHOP BULKELEY’S VISITATION OF DUBLIN 1636.

“The Church and Chauncell are downe. The tythe belongs unto the Deane of Christ Church being worth XXX111 libri per annum. The said Morris Lloyd is curate, who is allowed for serveinge of the cure VI libri per annum. There is not any Protestant in that parishe. The curate certifies that there is a house lately given by Mr. James Goodman of Laghnanstown, to be a school-house, and keepeth a young man, a papist, there to teach his own children and his neighbour’s children.” (2)

It is worthy of note that all through this early period from the time of the old Celtic Monastic schools and through all the vicissitudes of Norman rule up to the time of the Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church was the dominant factor in Irish life. The invasion took place under papal auspices; the old abbeys and monasteries were confirmed in their possessions from Rome and were continued until Tudor or early Stuart times. When later under Protestant ascendancy these religious orders were dispossessed, the Roman Church still maintained its hold upon the people whose loyalty has never been shaken.

Such meagre records seem to be all that we can piece together to throw any light on these early days. They are just sufficient to enable us to picture a small but growing agricultural and pastoral community, still making use of the ancient church and already concentrating in a “town”.

1. Christ Church Deeds 379 and 431.

2. Very Rev. M.V. Ronan. Archivium Hibernicum V111.

ANTE-NORMAN CHURCHES IN THE COUNTY OF DUBLIN.

By W. F. WAKEMAN, HON. FELLOW.

Extract from The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Fifth Series, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Jul., 1892), pp. 101-106

In a Paper which I had the honour, somewhat recently, of reading before a meeting of this Society, reference was made to certain clearly-marked changes in the style of not a few of our churches, which had been effected to suit the taste and feeling of new possessors of the several structures pointed to. The observations then made it is not now necessary to recall; but I may be permitted, on the present occasion, to adduce some further illustrations, all referring to churches or cellae which still remain in the immediate vicinity of Dublin, each and all of which form admirable subjects for students who would read in existing monuments the story of ecclesiastical architecture as it prevailed in Ireland from primitive times down to the period of the establishment of an Anglo-Norman power in certain districts of that country.

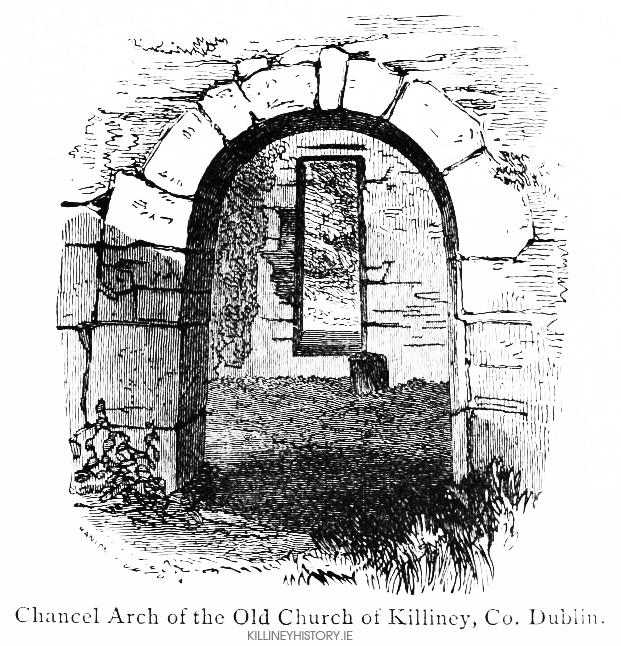

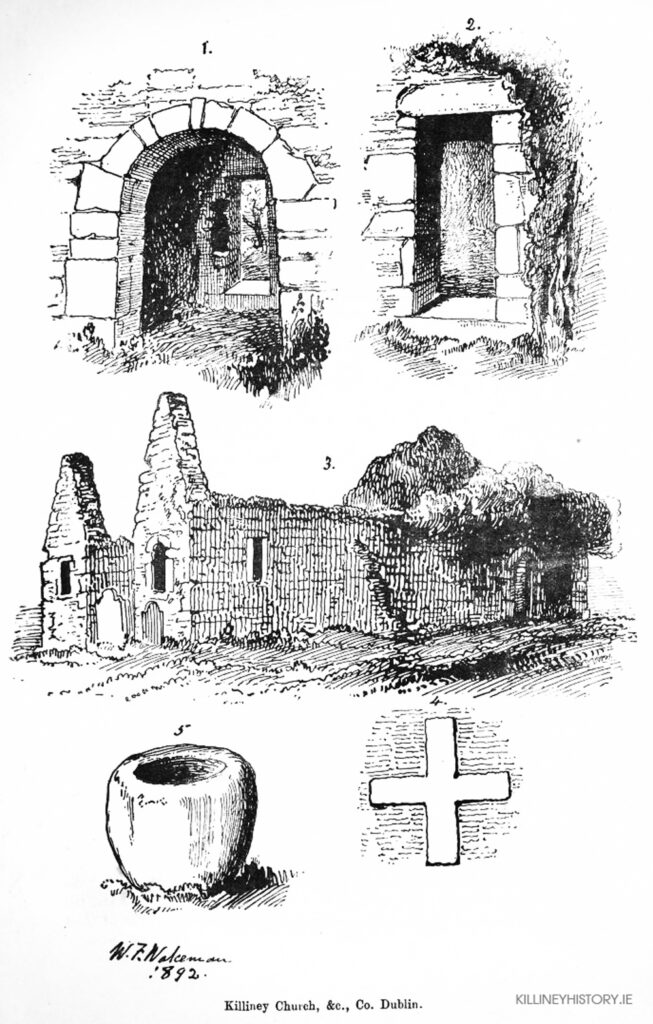

Of these venerable remains, the Church of Killiney must be considered in many respects the most valuable. The site, though closely environed by remains of pagan days, is possessed of extremely early Christian associations. The name of Killiney, as explained by Dr. Joyce, refers to certain daughters of Lenin, a notable person of royal descent who flourished towards the close of the sixth or in the earlier part of the seventh century. These were five in number; and although we are not permitted to know anything further concerning them, they rank amongst the saintly women of Ireland. The name of the place was anciently written Cill-Ingen, or Cill-Ingen-Leinin; i.e. “The Church of Lenin’s Daughters.” Whether the oldest portion of the remaining church can be supposed to belong to their time, viz. the seventh century, or to be of their foundation, I shall not attempt to discuss ; but, at any rate, at Killiney, we possess a teampull which exhibits all the architectural characteristics of an age which closely followed on the period of the advent of Christianity to Erin. Petrie -and not without reason- although unaware of some important points in evidence of extreme antiquity which the main structure presents, pronounced his opinion that it belonged to the sixth or seventh century. The original work consists of a simple nave and choir, connected by a semi-circularly headed arch. It should be observed that the choir or chancel is a feature extremely rare in connexion with very old Irish churches; but that it occasionally occurs is evident to all who have paid attention to the style of our pre-Norman temples. At Killiney, the nave and choir are certainly coeval; and in each will be found opes similar to those which occur in the round towers, and in churches of a primitive type. The original doorway occupies a position in the centre of the west gable (see fig. 2, Plate I.). It is flat-headed, a splendid example of its class, measuring 6 feet 1 inch in height, by 2 feet in breadth at the top, and 2 feet 4 inches at the bottom. In one respect this doorway is highly remarkable, presenting, as it does, what Bishop Graves would style a “Greek cross” carved in relief upon the under side of its lintel (see fig. 4, Plate I.). Only one other instance of the kind, as far as I know, can be pointed to, although, as at Fore, in the county Westmeath, Inismurray, county Sligo, and elsewhere, the sacred emblem may be seen carved over the opening on the exterior face of the wall.

A cross of the St. Andrew type occurs on the nether side of the lintel of Our Lady’s Church, Glendalough, a structure which there is reason to believe was erected by St. Kevin himself, and in which, according to tradition, he was buried. In Comte Melchior de Vogüe’s beautifully illustrated work on the “Architecture of Central Syria” (a copy of which may be seen in our National Library) will be found engravings of a considerable number of crosses, which occur carved on the lintel-stones over the doorways, or on the friezes of churches and monastic buildings of that country. These crosses are wonderfully like those which we find similarly placed upon portions of several of our earlier, if not earliest, Irish churches.

Dr. Graves has remarked that, as the Syrian buildings in which these crosses appear were erected in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries, it is probable that their form may have been introduced from the East by some of the pilgrim monks who visited Ireland in the very early period of the history of Christianity. The question of the origin of these peculiar symbols has not yet been definitely decided; but, as Dr. Graves has expressed his intention of following up a subject which he has made almost his own, we may hope ere long to have the mystery unveiled.

The choir arch (see fig. 1, Plate I.) is the next important feature to be noticed. It is perfectly Roman in design, except that, as with all our early buildings, the jambs incline from the ground upwards. The width, at the springing of the curve, is 4 feet 7 inches; that at the base, 4 feet 10.5 inches. The space from floor to top of the arch is but 6.5 feet. Of the church windows, but one (that in the eastern gable) remains in a state of perfect preservation. This characteristic ope is square-headed both within and without; is widely splayed; and, like the side lights, presents inclined sides.

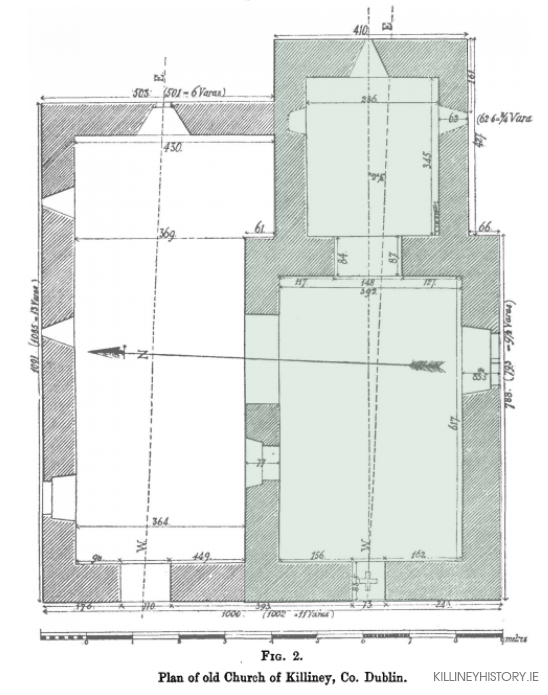

So far for the original church, which, I should add, measures upon the interior 35 feet in extreme length; in breadth, the nave is 12.5 feet; the chancel, 9 feet 6 inches.

At a period long subsequent to the original foundation, an addition, the style of which it will be well to compare with that of the building just described, was made on the northern side (see fig. 3, Plate I.). This -a kind of aisle- is connected with the primitive structure by openings broken through the north side wall. Its doorway (which appears in the accompanying etching) offers a striking contrast to that in the original west gable; and its eastern window is equally different from that in the ancient chancel, being larger, semi-circularly headed, and chamfered upon the exterior.

Some forty years, or so, ago, Killiney Church stood amongst fields, on a most delightfully picturesque slope, with scarcely a house to be seen by a person looking round from the ancient cemetery. It was approached from the main road by a rude “boreen,” on the left-hand side of which was a carn, station, or altar (like those one sometimes meets with in the south or west) by the side of which stood a hoary thorn-tree, which must have been several centuries old. Both tree and carn were considered by ancient people in the neighbourhood to be very sacred. They have long disappeared before the march of “improvements,” as has also the original “Mur,” or well-marked earthen Rath, by which the venerable cemetery was environed. Instead of this we find a hideous stone wall, built in the style usually adopted by the taste and feeling of Poor Law Guardians, who all over the country are destroying every trace of the picturesque which remained with our ancient parish churches.

NOTES ON THE ARCHITECTURAL DETAILS AND ORIENTATIONS OF THE OLD CHURCHES OF KILL-OF-THE-GRANGE, KILLINEY, AND ST. NESSAN, IRELAND’S EYE.

By J. P. O’REILLY, C.E.

Extract from Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Vol. 25 (1904/1905), pp. 107-116. Published April 30, 1904.

The church of Killiney is also mentioned in Mr. Wakeman’s Paper already cited; and he particularly calls attention to the Roman cross which is cut in relief on the under-face of the lintel of the western doorway. This old church is remarkable in the respect of having no history to speak of, and yet as showing manifest evidence of much use and continued frequentation, both by its extent, the changes which it seems to have undergone, and the vicissitudes that it furnishes clear indications of. Mr. F. E. Ball, in his excellent and carefully-detailed “History of the County Dublin,” thus speaks of it :- “The ruined church of Killiney has been pronounced by Dr. Petrie to be coeval with the oldest of the buildings of Glendalough, and to date from the sixth century. The original structure consisted of the nave and chancel; and to it were added, many centuries later, an aisle on the northern side. The primitive doorway in the western end, which bears on the soffit of its lintel a cross, the choir arch, and the east window are all very characteristic of early Irish church architecture (Petrie’s essay on the Round Towers,’ p. 170). The name of Cill-inghen-Leinin, the early form of Killiney, indicates that the church was founded by Leinin’s daughters, five holy women, whose names, according to the Martyrology of Donegal,’ were Druigen, Luigen, Luicell, Macha, and Riomhtach (6th March); and who are supposed to have flourished about the sixth century. Together with the lands, the church came into the possession of the Priory of the Holy Trinity before the English Conquest (Norman Invasion ?), and was subsequently confirmed to it by the Archbishop of Dublin and the Pope. After the dissolution of the priory, it became a portion of the dignity of the Dean of Christ Church; and appears to have been served in the sixteenth century by the chaplains of Dalkey. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, in 1615, it was roofless, as it has since remained.”

On page 96 of vol. i., Mr. Ball gives an excellent photo-engraving of the western doorway: (see also O’Hanlon’s “Lives of the Irish Saints,” vol. iii., p. 196). The plan of this church here with submitted (p. 112) presents characteristics of marked interest. The western door (of which a photo-engraving is given, as already stated by Mr. Ball, in his “History of the County Dublin,” vol. i., p. 96) is well preserved, and presents the following dimensions: height from sill to soffit of lintel, 187.5 cm. (6′ 1-87″); breadth at sill, 72 cm. (2‘ 4.35“); breadth under lintel, 61 cm. (2′); thickness of western wall on sill (south side), 83.5 cm. (2′ 8.88″), (north side) 84 cm. (2′ 9.07″); thickness of wall under the lintel (south side), 79 cm. (2′ 7.1″), (north side) 78 cm. (2′ 6.71″). The batter of the wall is therefore very well marked, and so far favours the presumed antiquity of the building. The material employed is much the same as that of the church on Dalkey Island, that is, granite roughly worked, and the mica-schist of the neighbouring hill, and that now to be found in Killiney Park, with the use of abundant “spawls.” The present south-eastern window of the nave is relatively large, mullioned, and well worked in granite, with full splay on the interior side; it may be taken as of relatively recent construction. There is no trace of there having been a small narrow opening here, as occurs in the other churches already described. The chancel, however, shows an opening at its south-cast corner, but in a ruined state, so that the original dimensions cannot now be determined; the remaining edge of the window is at 161 cm. (5′ 3.39″) distance from the exterior south-eastern corner of the building, and therefore is comparable in this respect to the corresponding opening of Dalkey town church, as described in my previous Paper. The eastern opening of the chancel is well preserved, has an aperture of 16 cm. (6.3″), and a height of aperture of about 76 cm. (2′ 5.92″), with perpendicular jambs, and so far showing no inclination of these sides. The splay on the interior is about 86 cm. (2′ 9.86″); but, on account of the ruined state of the work on this side, this measure can only be approximated. On the north side of the chancel there is an opening or cavity, as if for an intended window or light, nearly opposite the south-east opening, but with the walls in a partially ruined state. Wakeman and Petrie seem to have considered this chancel as being contemporaneous with the nave; but the thickness of the wall, 62 cm. (2′ 0.41″), (62.5 cm., 2′ 0.6″ – ¾ vara), the quality of the masonry, and more especially the broken line of junction with the walls of the nave shown on the interior face at the south-west corner of the chancel (see fig. 2), where the remains of the nave side-wall still project in jagged outline 8 cm. (3.15″) beyond the present chancel wall, point either to a reconstruction or at least to a discontinuance or suspension of the original design. Besides, there is hardly any evidence of bonding with the walls of the nave; nearly at all points there is simply juxtaposition. It is the same as regards the junction of the aisle with the nave and chancel.

This aisle was evidently a recent addition, and seemingly underwent more than one handling. There are two narrow openings in the northern wall of this aisle which look very old, the aperture being about 15 cm. (5.9″) in each. The north-west doorway, with its pointed arch and cut- stone dressing, is evidently recent. Of the western doorway of the aisle there practically remains but a portion of the southern jamb; its opening presented a width of 110 cm. (3′ 7.3″). So far as concerns the object of the present Paper, it is the dimensions of the building and the orientation which are of interest. The former show very distinctly evidence of the use of the “vara” unit, both as regards the details as well as regards the general dimensions. There is one very remarkable circumstance as regards the dimensions of the nave, the signification of which is not at once apparent; it is the absence of symmetry of the walls of the building, as regards its central axis; whether this was originally intended or is the result of subsequent alterations is by no means clear. The orientation as determined by hand-compass was found to be about 3° north of due east and west, and can hardly be taken as corresponding to the direction of the rising sun on the festal day of the saint whose name the church bears, the daughters of Leinin (6th March), which would correspond to a southern declination of about 6°. Hence it follows that the visual passing through the central line of the western doorway of the nave, and through the eastern opening of the chancel as it now stands, on to the horizon, would not give the correct day of equinox, but would correspond to about the 26th or 27th March, instead of the 21st. That is, on the presumption that such was the original intention of the builders, and not taking into account the ancient errors as regards the day of equinox and the subsequent corrections in the calendar.

As regards the visual line in question, it may be observed that the Latin cross cut in relief on the soffit of the lintel of the western doorway may have been intended to fix the point where the observer should stand in order to make the observation of the rising sun on the horizon, on the day of equinox, as indicated in the sketch of the doorway and eastern opening in question (Plate II). It may also be observed that the aperture of this eastern window would allow of the sun being seen through it from the point referred to, at its rising, on one day only in the year. This use of the cross would so far correspond with that of the incised cross on the rock in front of the church on Dalkey Island, referred to in my Paper on that building. Reference may also in this respect be made to the woodcut of the doorway in St. Mary’s church, Glendalough, given in Joyce’s “Social History of Ancient Ireland,” vol i., p. 318 (and mentioned as being taken from the Journal of the R. Soc. Antiq. Ireland, 1900, p. 310); in this case the diagonals of the soffit are represented in relief, and their intersection at the centre is marked by a rosette in relief. The other details are almost identical with those given in the sketch of Killiney church herewith submitted, and suggest an intention of obtaining a correct line of orientation or observation for equinox. That there was such an intention of making use of this eastern opening of Killiney church for the observation of the rising sun on the day of equinox is to some extent supported by the relation of the eastern window of the aisle to the western doorway thereof. This window is not only wider and in every respect more recent-looking than that of the chancel, but it was also divided and protected by a middle vertical bar, of which the socket is still visible in the sill of this window. Now, a line through the middle of the western doorway of the aisle, and through the bar of the eastern window thereof, gives a true east-and-west line; and it is probable that it was used for a more correct determination of the equinox than could be attained by the use of the corresponding line of the nave and chancel already considered.