Introduction

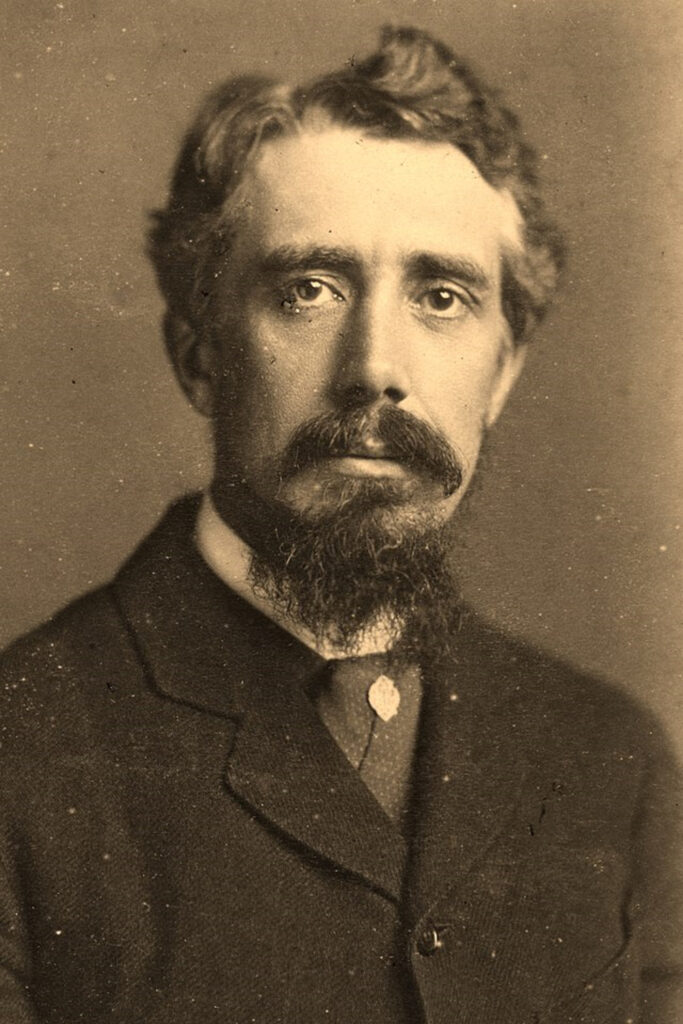

In keeping with the theme of transport which was celebrated in our recent ‘Killiney on the Move’ event, 25th-26th May 2024, we are pleased to reproduce this article courtesy of maritime historian, Cormac Lowth. This piece first appeared in SubSea Magazine, published by Diving Ireland, in the autumn of 2005. Edmund Dwyer Gray was a Killiney resident and his family home was Vartry Lodge on Strand Road, a house which has direct access to Killiney Strand. Edmund later went on to become Dublin’s Lord Mayor and his heroic actions of September 25th 1868 add to the story of his eventful but short-lived life.

Dublin’s Heroic Lord Mayor

By Cormac F. Lowth

There were a great many shipwrecks in the nineteenth century. By the standards of today, the navigational aids that were available to the mariner in the days when the majority of ships were still propelled by the wind, were extremely rudimentary. The weather forecasts from the Meteorological Office, that we frequently gripe about today when they get it wrong, were non-existent. The vast majority of coastal trade was conducted in small sailing vessels that carried little more cargo than a modern day juggernaut lorry. The magnetic compass, the chart and the sounding lead were the principal tools used in finding the way from one port to another. Great reliance was placed upon visual recognition of landfalls coupled with a knowledge of the tides and currents and much store was placed on weather lore, which is perhaps becoming a forgotten art. There were a great many jingles and rhymes to be memorised such as “A mackerel sky with mares tails, tall ships carry short sails” Taken all together, it was a poor dependence compared to the sophisticated navigational aids that we enjoy today. Every new year brought the same grim stories as the old, of hundreds of schooners, which were dependent on the winds and tides, being equally at their mercy as they were dashed to pieces on some rocky lee shore or aground on some offshore sandbank. All with a hideous annual toll of human life. A glance at a Board of Trade wreck chart of the British Isles for any specific year with its myriads of black dots representing shipwrecks will give some idea of the sheer numbers of ships that were lost. There was hardly a daily or weekly newspaper without some mention of shipwrecks, particularly in Winter. Though they would have been commonplace, the losses nevertheless frequently attracted great compassion from the general public and many people were inspired to great acts of heroism at the scenes of shipwrecks as they attempted to save the lives of those who were in peril. The brunt of these rescues were generally borne by lifeboat crews and coastguards who ventured out in small rowing and sailing boats and many of these rescue attempts were quite rightfully recognized with awards for bravery. There were also many individual acts of heroism that went away beyond the call of duty owed to others and one such deed was carried out on September 25th 1868 on Killiney Strand near Dublin by a man who would eventually become the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Edmund Dwyer Gray, 1845-1888.

Edmund was the son of a man whose statue stands today in Dublin’s O’Connell Street, Sir John Gray, who was the proprietor of the Freemans Journal and who had been knighted in 1863 for his efforts, as a member of Parliament, and of the Dublin Corporation, in having the Vartry reservoir in Roundwood built, which brought piped water to the citizens of Dublin. Doctor Gray and his family were wealthy. In addition to having a large dwelling named Charleville House in the then fashionable suburb of Rathmines, they had a summer home called Strand House near the old Ballybrack Railway station on Killiney Bay in South County Dublin. This house, which is a large castellated granite structure beside the Martello Tower, was later re-named Vartry Lodge. Killiney Bay is a curved expanse of scenic coastline that stretches from Dalkey to Bray and it abounds in Italian-sounding names such as Sorrento Point and Vico Road, given by early occupants who had taken the grand Tour. It is said to resemble the Bay of Naples. Along its shore lies some of the most expensive real estate in Ireland that includes the homes of superstars like Bono and Enya. It’s steeply sloping shingle beaches and rocky offshore reefs have seen many a shipwreck. At the end of September 1868, Edmund Dwyer Gray was spending some time at the family residence in Killiney, despite the bad weather that had persisted throughout most of the month. It was said that the weather was unseasonably bad throughout most of 1868 and a great many shipwrecks had occurred all over the east coast of Ireland. On the morning of the 25th an easterly gale was blowing directly onto Killiney Strand and a vessel had gone aground some distance from the shore and almost opposite the railway station. This proved to be the Portmadoc schooner BLUE VEIN and five men were seen to be clinging to the rigging as the seas swept over the stricken ship. The visibility was very bad with showers of heavy driving rain.

The renowned Harbour Master of Kingstown, (now Dun Laoghaire) Captain William Hutchison, who was also the secretary of the Kingstown lifeboat station, had a long and heroic history of involvement with the lifeboat. He had been notified of the plight of the BLUE VEIN soon after she had been driven ashore. He realised that conditions were so bad outside the harbour that it would have been useless to launch the lifeboat to attempt a rescue in Killiney Bay, a distance of several miles away. Instead, he managed to borrow some teams of horses from McCormacks, the local coal merchants in Kingstown and he had the lifeboat taken from the boathouse on its carriage and drawn overland to Coliemore Harbour in Dalkey. However, after the boat was launched, word was brought that the entire crew had already been rescued, largely through the efforts of Edmund Dwyer Gray and a coachman named John Freeney. Edmund, whose house was situated near the site of the wreck, was on the shore and he and Freeny both entered the water. Each of the five crew-members managed to gain the safety of the shore

The following report appeared in the Lifeboat Journal for 1868.

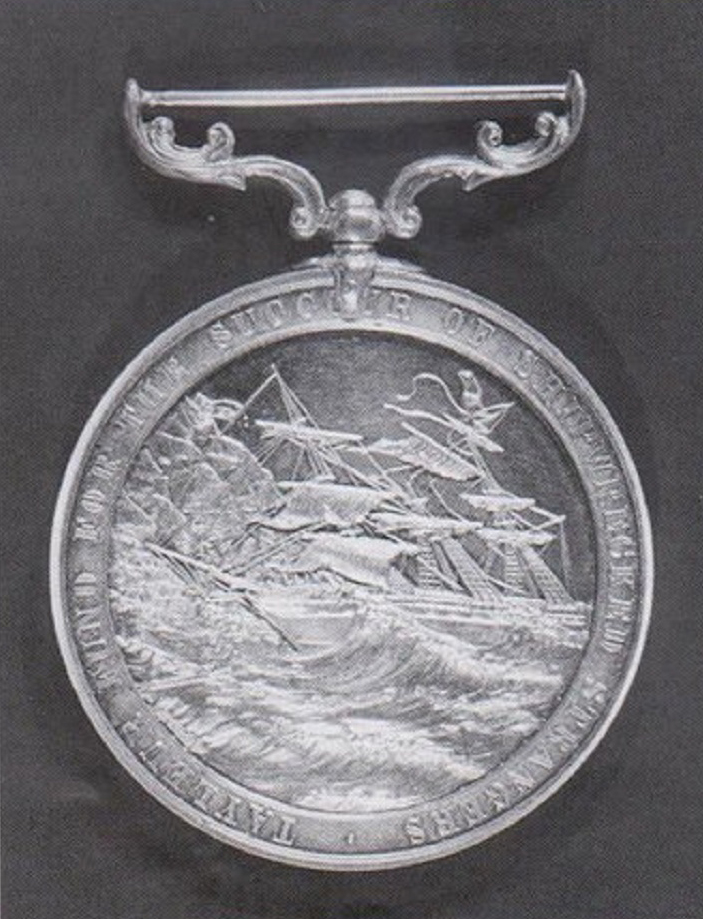

The Silver medal of the Society was voted to Edmund Dwyer Gray, son of Sir John Gray M.D. M.P. and a coachman, John Freeney, with £2 to the latter, for swimming out in a heavy sea and bringing a line on shore, and by other means assisting to save five men from the wreck of the schooner BLUE VEIN of Portmadoc, which, during an east south east gale, had stranded opposite Ballybrack Railway Station. A pecuniary award was also made to some persons who assisted on that occasion.

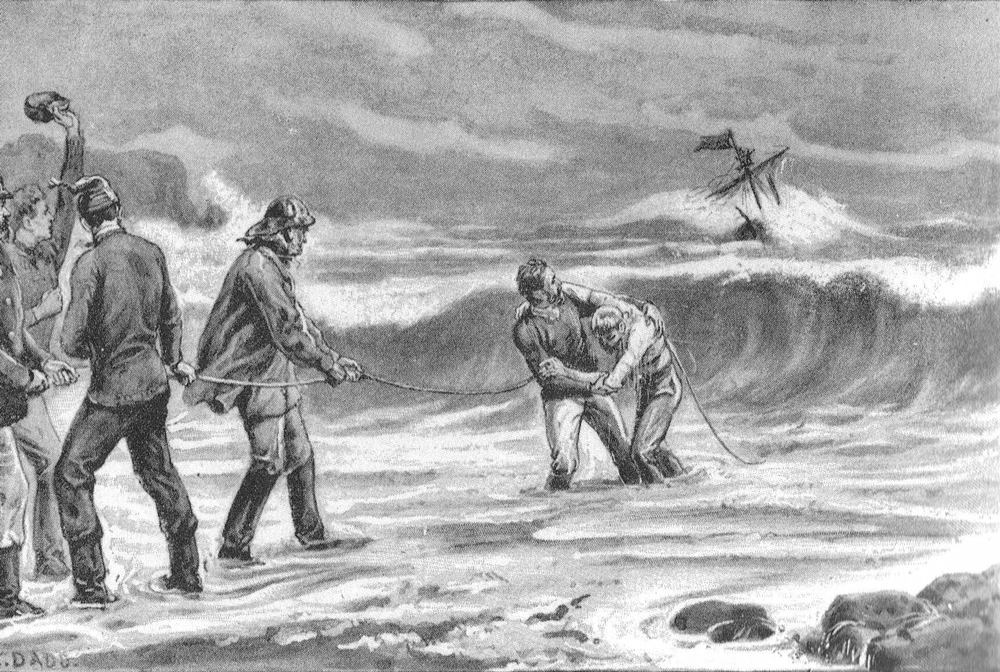

The vessel struck about two hundred yards from the shore. A line was attached by the crew to a spar and let drift from the vessel in the hope it would be brought to the shore by the waves. But the spar advanced only about a third of the way between the ship and the land and the line, consequently, did not come in.

A fisherman tried to swim out to the spar but he did not advance more than a few yards, having been immediately driven back by the waves. Mr Edmund Gray, who is an expert swimmer, then undressed and attempted to swim out, having a line attached to his waist, but when he got out about sixty or seventy yards, be was driven back. The crew on board then attached a cable to the ship’s boat and having launched the boat, it was driven in onto the beach where the rope was secured. Two of the men on board reached the shore by this means. When the third man was passing from the ship to the shore, the rope parted about midway and he was carried along parallel to the shore by the tide. He was rescued by Freeney who swam out with a line and dragged him in.

The ship still lay among the rocks and she thumped heavily seeming in imminent danger of going to pieces. The Captain and the other man who were still on board, hauled up the cable which was broken, attached a spar to it and cast it off, but from some cause, the spar made very little way in its progress towards the shore. After it advanced thirty yards from the ship, possibly owing to its not offering sufficient surface for the wind to overcome the friction of the rope in the water, Mr. Gray, seeing this, again undressed and having a line around his waist, one end of which was held by some men on the beach, swam out about eighty yards and, grasping the spar turned towards the shore, but soon after became exhausted. He was hauled in, bringing with him the end of the rope. For the last twenty yards he was drawn to the shore quite powerless, lying on his back and was almost insensible when he reached the land, but speedily recovered his self-possession. By means of this rope the Captain and the other man were enabled to reach the shore in safety.

The bravery of the two men was quickly acknowledged by the R.N.L.I. but in keeping with the accepted class distinction of the day, and with what would have been regarded as the relatively humble status of a coachman, the part played by Freeny did not receive the attention it deserved in the many newspaper reports that described the events. Both men were awarded the silver medal of the R.N.L.I.. and both were subsequently given the gold medal of the TAYLEUR Fund Committee. One can only wonder why such heroic rescues did not merit the gold medal of the Lifeboat organisation, which has frequently been referred to as “The Victoria Cross of the lifeboats”.

The following report appeared in the Irish Times.

On January 2nd 1869, a meeting of the Tayleur Fund Committee was convened at the Dublin Chamber of Commerce for the purpose of making awards to Edmund Dwyer Gray and John Freeney. Lord Talbot de Malahide was in the chair. Also present was the Lord Mayor, B. J Davitt, Mr. Alex Findlater, Alderman Meyler, Sir John and Lady Gray, Mr Hackett, barrister, John Paget, Capt. Ingram, A. M. Sullivan, John Carroll, solicitor. Henry Vaughan, Mr. Molloy, Mr. O’Connor, Mr. Stokes, Mr. R. W. Egan. Mr. W. Fry, George Smith, Mr. Mulvaney, Mr. Foxall and Mr. Lavy. Lord Talbot de Malahide was in the chair and when he rose to speak, he made the following address,

“It is customary on these occasions to make a few remarks. I shall be very brief. The events which caused us to meet, commends itself to all and sundry of every right-minded, of every Christian man, in the community. You are all aware that the Society now assembled, the TAYLEUR Fund Committee, was established in 1854 on the occasion of the lamentable disaster when the TAYLEUR was wrecked off the coast of Lambay. The circumstances at the time created great attention, it was melancholy in the extreme. A vessel starting for a distant land with a large number of individuals who were hoping to better their condition by expatriation, persons of different classes of life, some of them, I may say, of the highest respectability met their untimely fate. Among them was Mr. Codd, a brother of Thomas Codd. who was known to us all, and who took a leading part in the affairs of the City. The disaster created a great sympathy and a very considerable sum of money was contributed, both in this country and in England. Her Majesty was pleased to give a donation of £25, evincing by that, that the same willingness prompts her on all occasions to assist good undertakings. (hear hear)

After satisfying every demand on the TAYLEUR Fund, there was a considerable surplus and upon consideration it appeared to us that it could not be devoted to a better purpose than providing the necessities of the shipwrecked and rewarding the exertions of those who were foremost in rescuing victims from a watery grave. (hear hear)

We have frequently given donations for this purpose and although they have not been made in the public manner of our proceedings this day, I think, without any feeling or any wish to show ostentation, it is a good course to conduct these things in a public manner. (hear hear)

An example is contiguous. Whether for good or evil and it is useful that there should be, on certain occasions, a display of the recognition which follows noble deeds. The facts connected with the events which have brought us together are patent to all. We are going now to present medals to two gentlemen who have distinguished themselves in the highest degree and who have rescued five individuals from a most dangerous position. It is no ordinary man who has the power both of body and mind to come forward on an occasion of great peril. (hear hear)

There are many noble deaths. It is a noble thing to die on the field of battle fighting for the rights of one’s country. There are other great deaths, but if I was to choose a death, there is none I would sooner select than a death which would overtake me in the effort to save the life of a fellow creature. That indeed would be euthanasia. Gentlemen, I will not detain you any longer but conclude by reminding you that the ancient Romans were foremost in rewarding great acts done on behalf of the public. There were crowns of various kinds for military and naval powers but none ranked so high as the crown Cive Salvate. (hear hear)

The Chairman then called on Mr. Edmund Gray, who, on coming forward, was received with loud applause. Lord Talbot de Malahide said;

“Mr Edmund Gray, I have great pleasure in presenting you, on behalf of the TAYLEUR Fund Committee, this gold medal for distinguished courage in saving life from the BLUE VEIN at Ballybrack on September 25th last. I have very great pleasure, I repeat, in presenting this medal to you. You have deserved anything I could bestow on you for courage, energy and Christian feeling on that occasion. I would add, that in all this, you have shown the energy of your race.”

Mr Gray, in returning thanks to the members of the Committee, said,

“He felt certain that there was not one present, who, if placed in the same position, as he was on that melancholy occasion, would not have endeavoured as strenuously as he did to save human life”

Mr Freeney also returned thanks. Mr. Stokes proposed a vote of thanks to Lord Talbot de Malahide and the proceedings ended.

Mr Freeney did not get much mention in this report.

The TAYLEUR Fund was initiated in the aftermath of the disaster of 1854 when the new emigrant clipper was wrecked on the coast of Lambay Island off North County Dublin with terrible loss of life. The fund was drawn from a wide variety of sources. It consisted of donations from the general public and from various commercial interests, in response to an appeal that had been made at the time for money to aid the relatives of the victims of the tragedy and to help the survivors, many of whom had lost all of their earthly possessions in the wreck. It was decided to continue to administer the fund for a number of other purposes in addition to the original objective. The victims of future shipwrecks would receive help and a series of medals would be struck to be awarded for acts of maritime bravery. These were made in Gold, silver, and bronze. The obverse shows a depiction of the TAYLEUR against the rocks at Lamabay with the inscription Tayleur Fund For The Succour Of Shipwrecked Strangers, while the reverse was inscribed with the name of the recipient and details of whatever brave act they had performed. It is thought that about forty four medals were awarded during the twenty years that followed the TAYLEUR disaster. Three of these were of gold, the rest of silver. There are no known records of any medals having been awarded after 1875. Roughly half of the medals were awarded to people who had taken part in one dramatic rescue attempt during the great storm of 1861 at Kingstown Harbour when Captain Boyd and five of the crew of the guardship H.M.S. AJAX were lost as they attempted to rescue the crews of the INDUSTRY and the NEPTUNE as they were being wrecked on the East Pier. Such funds were normally wound up seventy years after the event when generally there would be little residual dependence upon the fund. The administrators of the TAYLEUR Fund seem to have been mostly prominent businessmen who were associated with the Dublin Chamber Of Commerce. The TAYLEUR Fund was wound up in 1913 and the residue was given to the R.N.L.I. towards the cost of providing the first motorised lifeboat at the Kingstown Station. There is a TAYLEUR Fund medal that belonged to a member of the Coastguard, Thomas Woodley, on view in the present Coastguard premises at Howth Harbour in County Dublin.

The aftermath of the BLUE VEIN rescues was not without some romantic moments. A young lady, Caroline Agnes Chisolm was on Killiney beach and was an onlooker as young Edmund was carrying out his heroic deeds. They appear to have fallen for each other straight away and they were married within a year. Edmund converted to Catholicism in order to marry Caroline. Throughout the rest of his relatively short life, Edmund was to become involved in the turbulent politics of the time. He became the proprietor of the Freemans Journal upon the death of his father in 1875. He entered the Dublin Corporation as a councillor and he became immersed in attempts to improve the housing, health and sanitation of the poor of the City. In 1880 he was elected Lord Mayor of Dublin and in the same year he was elected as a Member of Parliament for Carlow. He belonged to the more conservative wing of the Irish Party at Westminster and his relationship with the leader of the Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, was at times very stormy. His newspaper generally reflected his own views of the politics of the day.

In 1882, Edmund was elected High Sheriff of Dublin. In an editorial in his newspaper, he criticized the selection process of the Jury of a murder trial that was taking place at that time. He implied that the Jury was being selected on Religious grounds. The trial in question was of a young man, Francis Hynes, who had shot a man who had taken over a farm that he had been evicted from. The Judge in the trial, Mr. Justice Lawson, took grave exception to Edmund’s remarks and held him in contempt of court. He was sentenced to three months to be served in the Richmond Bridewell and he was fined five hundred pounds. Ordinarily, it would have been the duty of the Sheriff to convey somebody in that situation to prison, however, The judge resolved the dilemma by instructing the City Coroner to make the necessary arrangements. He was escorted from the court, in his carriage on his way to prison, by a troop of mounted police. Many people waved, thinking that it was a ceremonial guard of honour. On the way, the inspector in charge fell off his horse and his sword landed in Edmunds Lap. Edmund alighted from the carriage and helped him to remount. He served six weeks of the sentence and his fine was paid for by a public subscription.

In 1885, the Freemans Journal became a limited company and Edmund received £150,000-00, a huge fortune in those days. He used his influence through the newspaper and with his connections at Westminster to prevent the Mail contract being taken from the City Of Dublin Steam Packet Company and awarded to an English Shipping Company. In 1888, Edmunds health declined rapidly. He had chronic asthma and he was heavily addicted to alcohol. He died after a brief illness. His funeral to Glasnevin was said to have been one of the biggest ever seen in Dublin.

Just off the shore on Killiney Beach today, and opposite the site of the old Railway Station, there are some remains of a wooden hulled wreck in a few metres of water, which divers refer to as the ‘Slate Boat’. This is most likely the wreck of the BLUE VEIN. It lies not far from the remains of another sailing ship that came to grief on Killiney Strand in 1899, The Steel hulled ship, LOCH FERGUS. An oil painting by the Irish artist Edwin Hayes, RHA, that was painted in 1869, may have been inspired by the wreck of the BLUE VEIN. It depicts a shipwreck off Killiney Beach and a lifeboat being launched. It was sold at auction recently by James Adam & Co. for €29,000. (2005)

References

Various Contemporary Newspapers.

Coastguard Bravery awards 7. Dr. Roger Willoughby.

Dictionary of National Biography.

Bound for Australia, Edward J. Bourke.

Wreck and Rescue on the East Coast of Ireland, Dr. John de Courcy Ireland.

Annual Lifeboat Register 1868. R.N.L.I..