New Book Launch

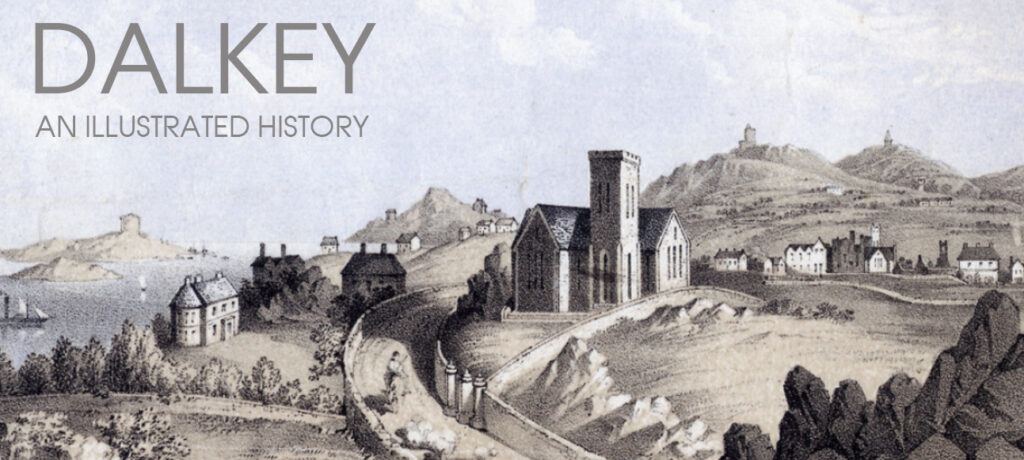

‘Dalkey: An illustrated history’ by local author John Martin has just been published by Eastwood Books. It’s on sale for €20 at Dalkey Castle Heritage Centre and in bookshops.

The book is aimed at both the general reader and those with a particular interest in the local history of the area. The time period this work explores extends from the earliest settlement about 5,000BC to the present day, covering Dalkey, Bullock Harbour and Dalkey Island. It also examines the urban development of Dalkey in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, looking at topics such as housing, transport, and services. The final two chapters provide brief pen-pictures of people who helped shape the development of Dalkey. Each chapter is illustrated with historic maps, engravings, paintings and photos.

To complement the recent KHS outing to Dalkey Island, here are some extracts from the book:

There are two reasons why any history of Dalkey should begin with Dalkey Island. First, the island contains the site of the earliest known settlement in the wider Dalkey area, dating back about 8,000 years. Second, the place-name itself derives from the Norse Dalk Ei, a direct translation of the older Irish name Deilg Inis, mean¬ing ‘Thorn or Dagger Island’. Visitors arriving at the landing-pier on the west side of the island could be forgiven, however, for overlooking such a historic site, as the grassy promontory on their left at the north-west tip of the island offers no visible evidence of its past.

In the late 1950s, archaeologists led by G.D. Liversage carried out a series of excavations within the promontory area, which showed that it had been occupied at different times from about 6000 BC (Mesolithic) to the Iron Age.2 The earliest material included pottery and implements, some with radiocarbon dates from 5970–5560 BC. Finds from the later Neolithic period included implements known as ‘Bann flakes’, dated to around 3340 BC; a human skeleton from that era was also found under a refuse heap of sea shells.

On Dalkey Island, the spread of Christianity was reflected in a stone church, a cross inscribed on a rock face and a holy well, although the latter may have derived its origins from pre-Christian practice. Up to the nineteenth century the ‘Scurvy Well’ was believed to cure eye conditions.

Dalkey Island, along with Dalkey itself, came into the possession of the archbishop of Dublin in the early twelfth century; both formed part of the archbishop’s manor of Shankill in 1326, when the value of the annual rental of grazing on the island was estimated at 12d. It is interesting to note that when the Board of Ordnance acquired ownership of the island in 1807 in order to build a Martello tower and a gun battery the archbishop was still listed as one of the owners. The island appears to have been uninhabited and used for grazing throughout the intervening centuries.

Any tranquillity experienced by the island was shattered in the closing decades of the eighteenth century, at least for one Sunday each year at the end of August or in early September. At some time in the 1780s, and certainly by 1787, a fleet of boats carrying the ‘King of Dalkey’ and his retinue sailed from the Liffey quays to Dalkey Island, where his coronation took place amidst lavish festivities. The event was wit¬nessed by thousands of people crowding both the island and the opposite shoreline; as Dalkey was only a tiny village at the time, most were visitors from the city and suburbs.

When the royal barge arrived with flags flying and music playing, his majesty in¬spected his territory, surrounded by his dukes, generals, bishops and courtiers, many of them inebriated from the celebrations which had begun the previous evening in the city centre. Divine service took place in the ruined church, where a sermon was preached by the lord primate of Dalkey. Following speeches and debates on the politi¬cal topics of the day, the king’s health was drunk and a festive meal was served out¬doors.

An account of the proceedings was published as the Dalkey Gazette in some of the Dublin newspapers shortly afterwards. The whole event, while mainly convivial, had a political undertone; the American and French revolutions had sparked intense debate in Ireland, and the mock ceremony on Dalkey Island satirised the extravagant pomp of the British monarchy. The last King of Dalkey was Stephen Armitage, a popular Dublin bookseller. His speech in 1797 made it clear that his office was elec¬tive and that it was for his people to decide whether he was worthy of another year:

‘The crimes of royalty, its tyrannies, its treacheries, and its rapacities, have rendered it suspicious everywhere—from that suspicion it is my wish to vindicate for ever him who wears the crown of Dalkey’.

A major uprising against British rule in Ireland, led by the United Irishmen, took place in 1798 but was suppressed with considerable force, with the death-toll ex¬ceeding 10,000. A French expeditionary force that landed in County Mayo was also defeated. In those circumstances, the revelries on Dalkey Island did not take place that year.

The British military authorities decided to strengthen their coastal defences in both the UK and Ireland. This included the building of 130 Martello towers on the southern coasts of England; the name, though not the design, derived from a Royal Navy attack on a tower at Mortello Point in Corsica in 1794. Following the Act of Union in 1800, responsibility for Irish coastal defences lay with the Board of Ordnance in London, which had a substantial budget. In late 1803 the new mili¬tary commander of Ireland, Lieutenant General Cathcart, toured the coastal defences with Captain Birch, an officer with experience of the Martello towers in Minorca. About the same time, intelligence was received that suggested a threat of invasion of Ireland by landings on the east coast, and in June 1804 Lieutenant-Colonel Benjamin Fisher, Royal Engineers, was authorised ‘to superintend the construction of all such towers, field or other works as may be undertaken’, and the construction of the Mar¬tello towers to defend the coast of Dublin and north Wicklow began.