KillineyHistory.ie would like to thank Holy Trinity Church Killiney for allowing us to reproduce the following piece from ‘Holy Trinity Church Killiney 1858-1996, A Parish History’ which was published in 1996. The recollections of Arthur Haughton who was born in 1903 and who lived in the area for all of his life is a fascinating record of many aspects of daily life and local history which would otherwise be lost forever.

The original attendance roll books which date from the day the old school opened in January 1880 give details of the name, address, date of birth, and attendance of each pupil and also the father’s occupation. A number of these family names are still on the present school roll. Arthur Haughton who was born in 1903 attended the school in the early 1900s and has lived in the area all his life. Now aged 92, he is fit and well with an incredible memory. As we read through the School Register, he remembered names of people who were of his father’s generation and when we came to his own era he could remember boys’ names, where they lived and their fathers’ occupations. All these details were in the register, but he could list them off from memory and could remember the antics that some of them got up to in their youth.

Here are just a few of the stories he told of his early years — being caught `mitching’ and other events which went down in history. He remembers hearing the story that before the RMS Leinster was torpedoed in 1918, a lady living in Sorrento Terrace had seen the U-boat lying off Dalkey Island and is said to have notified the police who took no heed of her. Though the Leinster was a civilian ship, it was destroyed because there were British soldiers on board. Arthur was in the Boy Scouts, whom he still refers to as the Baden Powells, which were based in Dun Laoghaire at McCormick’s coal office. One of their activities was to meet the ships with refreshments. They carried trays with cigarettes, tobacco, sandwiches and tea with milk and sugar added (they weren’t given the choice!). The Scouts were on duty when the dead and wounded were carried in from the Leinster. There were hundreds killed that day and the military were buried by rank in a graveyard on the north side of the city.

Speaking about his schooldays, he talked about Miss de Saix who was the Principal at the time. She was a lovely lady, who took a great interest in everyone and gave extra tutoring to the children who needed it. Often too, if past pupils who were not happy with their job, spoke to her, she would tutor them and many moved on to better, happier careers. Miss de Saix was fluent in many languages and when the teaching of Irish became compulsory she went on a course in Kerry during the holidays, to learn the language. She gave music lessons to supplement her wages which is not surprising as her salary, according to the records, was a mere £44 per annum supplemented by £10 from each of the two parishes.

The school hours were from 9 am until 3 pm with a half-hour break. In December there was a big Christmas party and from time to time they had concerts. Preparing for a concert was time consuming and therefore they were not annual events. At one concert he remembered dancing a hornpipe, and to make him look authentic Mr Murnane slipped him an old clay pipe, which he put into his mouth. When Miss de Saix started to play the piano everyone began to laugh, so she turned around to see what was so funny and discovered Arthur with the pipe.

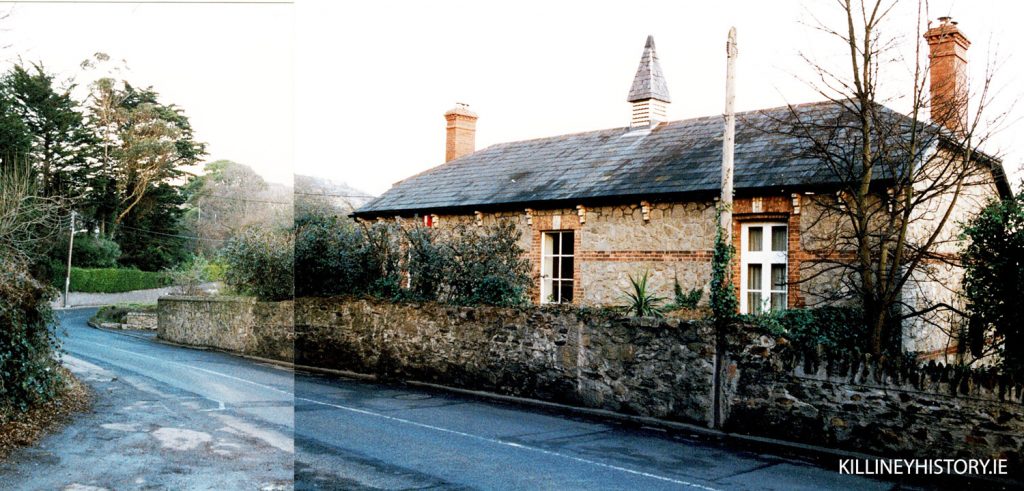

There was no school playground; the space adjoining the school was not acquired until after the school building was bought in 1932. Instead, they had the use of a field, owned by Judge Bramley, further down the road, next to the rectory, which was beside the school.

Arthur admits he was not a model pupil; in fact he was frequently in trouble, particularly for playing truant. On one occasion during school hours, he and two friends were caught collecting sticks to make a fire. The local landlord Mr. Talbot discovered them. He sent them down to his farm to work for the day as a punishment. At the end of the day, when the other labourers were paid 2/6d, the boys asked for their money. Mr. Talbot walked towards his gun, which was hanging on the wall…. “What did you say?” and the three boys ran off so fast that they became wedged in the doorway. In fairness to Mr. Talbot, he sent them their money the next day and it was then that their parents discovered they had been absent from school and his father gave him a clip on the ear.

They used to light a fire on Mullen’s Hill; they couldn’t do it on Killiney Hill as Andy Murphy (the Park Ranger) would have caught them. Once, they killed a chicken and boiled water in a bucket to make soup. They also cooked turnips. They had a hideout on Mullen’s Hill (Rocheshill) where they had made two ‘tunnels’ about 20 to 40 yards long, leading in and out of the gorse bushes. One day, when they were absent from school, their fire drew attention to them. The priest from Ballybrack and Canon Stoney went to investigate. Perhaps they saw the smoke, or perhaps they caught sight of the boys on their way through the village. The boys tried to escape, but the two men had positioned themselves at the entrance and exit of the tunnels. They were marched through Killiney village, and word must have preceded them, as the villagers were all out to laugh at them as they passed. He said this was much more humiliating than the caning Miss de Saix gave them – 3 slaps on each hand – when they arrived back at the school.

During 1914-1918 War, many Irish men joined the Army and went off to fight in Europe but Arthur was still attending school. In Ireland at the time, refugees came over from Britain and Europe. He remembers four Belgian refugee children from Flanders, who were evacuated to Killiney, three girls and a boy. Two of the girls stayed with gentry and came to school by car. The other two, a brother and sister stayed with Mr Keegan the butcher in Ballybrack. Miss de Saix could speak fluently to them, but the school children could communicate only by using sign language. At lunch time they shared their sandwiches which were only bread and butter. The difference was that the Belgians had French bread, which was specially made for them. The Government designated a baker to produce French bread for these evacuees who were scattered all over Dublin, to make them feel more at home. By exchanging lunches, the children had the novelty of tasting and enjoying each other’s bread. These refugees stayed only a year, and then returned home via England.

Easter of 1916 is a date in Irish history which has been well documented. Asked how they had heard of what was happening in Dublin city, Arthur said the Rising started so suddenly that in Killiney they were not even conscious of it. His father travelled by train to Dublin on business, unaware of what was happening in the city. When he reached Westland Row station (now known as Pearse Station), he stopped to ask a policeman for directions to his destination. As they spoke, the policeman was shot dead beside him. Several police officers came running up and he was pushed aside while they attended to their colleague. He was deeply shocked, as he could so easily have been killed.

In those days there was neither television, nor radio, but they could read about events in the newspapers the next day. They did not always have to wait until the newspapers came, because there were a few telephones, especially in the large residences and local businesses. During the Rising they went up to Killiney Hill and Dalkey Hill at night. Looking towards the city, they could see the glow from the fires and hear the cracks and booms from the gunfire.

During the 1914-1918 War, Killiney Castle was used as the local Headquarters for the Army. After the Rising of 1916, one had to apply for a permit if one wished to travel to and from the city. Quite a few families still have these in their possession. The Haughtons kept their permits and framed them. One was much more worn than the other as Pearl, the only girl in the family, travelled more frequently into the city.

In those days children were expected to do chores. One of these was to collect wood, and it was not just for their own family use. They were good at gathering kindling for the old people in the area. The best kindling was the burnt remains of gorse fires. Not only was it of benefit to the elderly, but also for the regrowth of these bushes, as it removed the damaged wood and made the whole area fresh and green for the next season.

Another job Arthur had as a child was at Glenalua Lodge, the home of the Le Fanu family. He had to look after and feed the hens, and he was paid 6d per week and half a dozen eggs to take home. More often than not he stayed on to play with the Le Fanu children. Some of his money was spent on cigarettes. In those days Woodbines cost id for a packet of five and there was an uproar when the price changed to 2d. Children under the age of 12 rolled their own – using brown paper. There was under age smoking in those days too! He remembers as a child being in the church with a friend smoking a cigarette beside the stove. They heard Canon Stoney coming and his friend quickly threw his into the stove, but Arthur got caught.

In church, the Haughton family sat in the two back rows, just inside the main door. The Haughton adults sat in the back row, with the children in front and they got a clip around the ear if they misbehaved. These two pews have since been removed.

When Arthur was shown the wedding photograph of Miss Kathleen Waterhouse, taken from the gallery in Holy Trinity Church on August 12th 1912, he said that it brought back memories of the beautiful clothes and hats that were worn at the time. There were several wealthy families in the area. In those days it was expected that the members of the so-called ‘lower classes’ would salute the gentry: women would curtsey and men would touch their forelock or raise their hat. He recalled one day, when he was carrying out one of his regular Saturday jobs, that he went to see Granny Hall, as she was known locally, who had a dairy. To reach the dairy, one could take a short cut past Glenalua House where the Waterhouses lived. On this particular day there were puddles everywhere, and as they passed by, Mrs Waterhouse and her daughter Miss Annie were there; Mrs Hall, who was standing in a puddle at the time, curtseyed and her skirt got wet. Mrs Waterhouse said ‘Now Mrs Hall, you needn’t have curtseyed.’

Road surfaces were not the best, and they used to be steamrolled. When the weather was dry there was dust everywhere, and puddles when it was wet. Though they wore shoes, they preferred to run around barefoot, but they always had to have their shoes on when their father was at home. Transport at the time was by train or tram. The tram service which ran from Dalkey was excellent. They were meant to leave every 3 minutes, but Arthur said it was more like every 5 minutes! The tram from Dalkey went as far as Nelson’s Pillar in the centre of Dublin.

Arthur was only 21 when his father died at the age of 46 and, since his mother was an invalid, he as the eldest had a responsibility to care for the family of 5 children. He was a slater, and he used to carry out work on Holy Trinity roof. He also worked in the public houses in Killiney Village – The Druid’s Chair which is still there and beside it was Victoria Hotel, later known as Jades restaurant. In earlier times this had been a stage for the stagecoach which travelled up from Wexford to Dun Laoghaire. As Killiney Hill Road was so steep, the stagecoach stopped at Killiney House to change horses; the passengers alighted and walked up the hill to the hotel for refreshments, while the stagecoach came up empty and met them again at the hotel. It was then a downhill run through Dalkey to Dun Laoghaire.

Arthur’s uncle, Richard, was well known in the area as a horticultural engineer. His advertisement appears in Porter’s Post Office Guide Directory. He installed central heating in greenhouses, which allowed the cultivation of tender plants. Arthur remembers plants and fruits being grown in Killiney Castle hothouses.

In the Preachers’ Book there is a column for comments. In the early 1920s this space was often filled by remarks about the extremely bad weather conditions. Arthur, when asked if he remembered anything in particular, said they used to get very harsh, black ice, which was particularly noticeable on Darcus’ Lake in the grounds of Rock Lodge, then called Plas Newydd. He also remembers hearing about the Great Storm in February 1903. The newspaper had photographs of huge trees in Phoenix Park with their massive roots in the air.